The ecosystem of press criticism is probably as strong now as it has ever been: columnists like Jack Shafer of Politico, public-minded academics like Jay Rosen of NYU, in-house critics like New York Times public editor Margaret Sullivan. There are press watchdog organizations and regular press reporting and criticism in places like Gawker and major newspapers and the Poynter Institute and, of course, Nieman Lab and Nieman Reports. But after this month, there is one fewer journalism review in the United States.

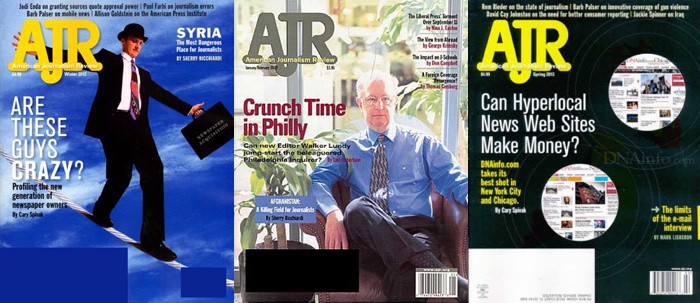

When Lucy Dalglish, the dean of the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland, announced that the American Journalism Review would be ceasing publication, the world of journalism mourned. But the AJR that most of them probably missed hadn’t existed for about two years, not since editor Rem Rieder — its last paid employee — had left to become an editor and columnist at USA Today. And while Rieder’s departure was noted at the time, the two years that followed did not bring about thinkpieces about the end of press criticism — precisely because that ecosystem was so robust. Richard Pollak, the cofounder and editor of the 1970s journalism review (MORE), told once told me that even if that magazine hadn’t folded in 1978, there was no need for it now. The Internet, he said, had made press criticism abundant, varied, and pervasive.

While AJR’s strongest partisans, including Rieder and longtime contributor Carl Sessions Stepp, feel that journalism reviews do something that these other outlets cannot, it seems clear that the mourning for AJR isn’t so much about the loss of the institution itself (which barely existed anymore, anyway), but about the loss of the nameplate, which represented an ideal: When journalists were questioning power, journalism reviews were questioning the institutions of the press.

The American Journalism Review was born at the tail end of a journalism review movement, in a time of ethics and accountability reform in the American press. It died this summer as classroom tool — one that was still doing important work, but which was no longer the powerful voice of critical analysis of journalism that it had once been. And its demise highlights press criticism’s struggle for a viable business model.

When AJR was founded as the Washington Journalism Review in 1977, two other reviews dominated the field. The Columbia Journalism Review, which launched in 1961, was a slightly stodgy, establishment-minded, but well-respected publication. The anti-institutional journalism review (MORE) debuted in 1971 as a response to changing attitudes in newsrooms among younger reporters who had come of age in the 1960s and were more likely to challenge the status quo. (MORE) was inspired by a spate of regional journalism reviews that sprung up in the 1960s, including in St. Louis, Colorado, Southern California, and most notably Chicago.

The sixties and seventies were the journalism review’s heyday, and Roger Kranz launched the Washington Journalism Review at the tail end of that peak, hoping to split the difference between being a national review of journalism like CJR or (MORE) and being a local, Washington-based review. Kranz was still in his 20s, and sold his Volkswagen to pay for the magazine.

The cost of running a journalism review was always prohibitive. (MORE) was supported, for most of its life, by checks from its publisher’s personal fortune. The founders, Richard Pollak and J. Anthony Lukas, lucked into meeting the grandson of the founder of Manufacturer’s Hanover bank, who believed in their cause. It had been transferred twice for the cost of assuming its mounting debts by the time the Washington Journalism Review was founded. In 1978, the last owner turned over (MORE)’s last valuable asset, its subscription list, to Columbia Journalism Review. The Washington Journalism Review changed hands similarly in 1979, to Jessica Catto and her husband, former ambassador Henry Catto. Eventually, the Cattos also decided that institutional support was the only way to keep a journalism review going, and they donated it to the University of Maryland Foundation. The dean of the journalism school, Reese Cleghorn, led an effort to establish a $2.5 million endowment to run the magazine, but even in its most fiscally flush days, the review operated hand-to-mouth.

Susan Keith, an associate professor of journalism and media studies at Rutgers University (and a member of my dissertation committee) noted in an email that:

…there’s a basic difficulty with the journalism review business model. Whereas many commercial magazines make significant portions of their revenue from advertising, supplying companies with a platform for reaching a fairly large and well-defined audience — women interested in fitness, men passionate about fashion, hunters, Apple computer enthusiasts, etc. — the target audience for journalism reviews is small and growing smaller. There really aren’t many companies that sell products used only or primarily by journalists — and for which journalists, as opposed to publishers or station managers, have purchasing authority. News organizations that might be the targets of criticism from journalism reviews aren’t likely advertisers either. So that leaves a logical advertising base of only the foundations and schools that offer fellowships and prizes to journalists or companies trying to influence journalists’ opinions.

Even with foundation or university support, these reviews struggle to stay afloat. Even Steven Brill, the successful journalist and entrepreneur in his own right was unable to make a magazine about the media — Brill’s Content — last.

In 2004, Gene Roberts, the former Philadelphia Inquirer editor and a professor at the University of Maryland, headed a committee to raise money to establish a new endowment for both AJR and CJR. At the time, AJR, which had changed its name in 1993 under Rieder’s editorship, operated on a budget of $1 million per year, while only bringing in $650,000 in revenue. By 2007, the operating budget was down to $800,000.

Roberts did succeed in raising some money, and in getting AJR and CJR to agree to publish in alternating months, but by the time Dalglish came on as dean at the University of Maryland, things had gotten progressively more bleak. According to Dalglish, her predecessor, Kevin Klose, had managed to secure a two-year grant to keep the magazine running, but Rieder was the only remaining staff member. According to Dalglish, control of the magazine had been transferred from the University of Maryland Foundation to the College of Journalism, and in order to keep even Rieder, his salary had to be reduced. After Rieder left, a group of Maryland journalism faculty turned AJR into a capstone project for its undergraduate students, focusing on entrepreneurship and new models of digital journalism, and the magazine became an online-only operation.

According to Dalglish, AJR ran for its last year on a budget of $100,000, only 10 percent of the $1 million budget that already felt tight in 2004. She said that even that sum was only possible because she asked for special permission to use money budgeted to Kevin Klose’s salary to support the magazine while Klose was away on leave. When he returned, the numbers finally became unworkable.

“If anybody thinks this is an experience that filled me with glee, they’re wrong,” she said of having to close AJR.

Faculty at the University of Maryland understand her decision. Stepp had a byline in every issue of AJR for 25 years. “It’s not hard to understand what happened. It’s just sad,” he said. But despite his sense of loss, he doesn’t blame Dalglish. “She didn’t want to kill it. It’s not like some cost-cutter came in with an ax. She was a strong, solid, respected journalist who fought for it for a couple years and just couldn’t make it work.”

But while the monetary decision may be understandable, Stepp still knows that something important to the practice of journalism has gone by the wayside. “I think that what gets lost is a reliable organization that is willing to devote itself week-in and week-out to serious journalism criticism and reporting about journalism,” he said. “There’s no substitute for being there. It’s one thing to say that the nature of the copy desk is changing, but it’s another to go sit on a copy desk for a few nights and watch what they do and talk to them about it. And newsrooms would let you do it, too. You would tell them you’re writing about a topic and they would give you the run of the place, let you talk to people.”

Rem Rieder made the same argument, pointing specifically to AJR’s coverage of the Duke lacrosse rape story:

I think there is still a place for the kind of definitive story on something. There’s room for the really in-depth look at what went wrong or what really happened. And for me, when AJR went out of that business — which is before it really went out of business — we could do that.

I was on a panel about the Duke lacrosse thing and I realized that story hadn’t really been told, so I had Rachel Smolkin do it. That kind of in-depth, heavily reported, non-ideological reporting is something that journalism reviews are best suited to do.

Victor Navasky, the chair of the Columbia Journalism Review, feels the loss of his former rival publication acutely. “With the blogosphere, there is a lot more of opinion about journalism,” he said. “But there is no acceptance of what the standards are and no general agreement about what constitutes the best press criticism and what the best way to do it is.”

CJR’s editor, Elizabeth Spayd agrees. “At a time when journalism’s ethical standards are in flux, and even its place in public life, losing a another media monitor is a loss for us all, even for a competitor like us,” she wrote in an email.

And former CJR editor Mike Hoyt also wrote an encomium to AJR, praising it not necessarily as a unique voice, but as a complementary one.

Stepp said that he is sad that the journalism community can’t find a way to support another serious journalism review. But he and Navasky and Rieder all still believe that there must be a way to fund a serious, in-depth publication about the press.

In his position as editor-at-large and media columnist for USA Today, Rieder has noticed a “terrific interest in media issues among the general public,” he said. “I’ve been at USA Today for a couple of years, and I write a couple of columns a week, and I’ve been surprised at the audience for some of them. I think there’s still very much a place for it.”

Stepp sees things very similarly, maintaining a sense of optimism. “There is such a community of professional journalism lovers,” he said. “You know these people. Not journalists, but the people in your church, in your community. The people who are well educated and have opinions about journalism. There’s such a community out there, that maybe if we get them to contribute their 10 bucks or 30 bucks a year, we could make it work.”

Kevin Lerner is an assistant professor of communication and journalism at Marist College. He earned his doctorate in journalism and media studies from Rutgers University, where he completed a dissertation entitled “Gadfly to the Watchdogs: How The Journalism Review (MORE) Goaded the Mainstream Press Toward Self-Criticism in the 1970s.”