Did The Washington Post correctly guess your age and income, based solely on the apps on your phone? (For the record: I am, based on my phone apps, “a single guy younger than 32 who makes more than $52,000/year.”)

The guess-your-age quiz accompanied a story by Post reporter Caitlin Dewey about a much wonkier research paper on modeling how app usage can predict certain demographic attributes. The personality quiz feature was built in-house by a Post team, and was one of a rather expansive collection that also includes a straightforward traditional quiz, a knowledge quiz, a timed quiz, a map quiz, and even a spiffed-up “Who said it?” quiz.

The guess-your-age quiz accompanied a story by Post reporter Caitlin Dewey about a much wonkier research paper on modeling how app usage can predict certain demographic attributes. The personality quiz feature was built in-house by a Post team, and was one of a rather expansive collection that also includes a straightforward traditional quiz, a knowledge quiz, a timed quiz, a map quiz, and even a spiffed-up “Who said it?” quiz.

“She personalized this story for the user, making it an experience where you can learn more about yourself by actually engaging with the story. It makes the story hit home with the user much more than if they were only reading,” said Greg Barber, director of digital news projects at the Post who also works on strategy and partnerships at the cross-newsroom collaboration The Coral Project. “Having more colors in our palette than just text and photos and video can be really helpful in telling a particular story.”

The Post’s story tools team builds the infrastructure behind quizzes, as well as an array of other tools aimed at getting its readers to do more than read: It’s responsible for game-like features like debate bingo, fantasy brackets, and Oscars ballots, but also ones like Notes (known as Knowledge Map in an earlier phase last summer).

Until recently the story tools team was dubbed the “games” team, because it had built a suite of quizzes and similar interactive features that would be offered as part of the Post’s publishing platform Arc, which it’s licensing to other publishers. The tools built since are intended to be part of the Arc package as well.

Until recently the story tools team was dubbed the “games” team, because it had built a suite of quizzes and similar interactive features that would be offered as part of the Post’s publishing platform Arc, which it’s licensing to other publishers. The tools built since are intended to be part of the Arc package as well.

“We were making ‘games,’ but that name turned out to be not entirely descriptive of what we do, and that’s when we looked around for another name,” said Alex Remington, the product manager who helps shepherd these tools into existence.

“Early on, we were going to build a crossword app and dive into the crossword space,” Jen Kastning, software development manager who heads up the engineering side of the story tools team. “Then we realized there was a big need in the newsroom to create more tools now, to help reporters tell their stories and also to help our end users interact more, so that they’re not just reading an article, but taking a quiz, participating in a poll, filling out a bracket.” Kastning leads a handful of developers out in the Post’s new Reston, Virginia offices.

The benefit of an interactive feature like a bracket is that visitors are encouraged to return to the Post’s website and vote over several rounds, then return to see who (or what) has been crowned the champion. How the team determines whether a tool was useful (and used fittingly) varies, but there are some simple indicators. Barber pointed to this year’s beer madness bracket, which attracted about 16,000 votes in the final round (and more votes than last year’s bracket), as an example of what was considered a successful incorporation of a non-traditional storytelling tool. Similarly, for one-off polls — such as the one asking readers what recipe Dana Milbank should use when he cooks and literally eats his column about Trump — the team monitors total votes (2,549 at the writing of this story) and repeat traffic the story is getting.

Dewey’s phone apps-personality quiz ended up attracting millions of visitors, which forced the team to revisit and make improvements to the backend architecture (“Virality was a good problem to have, but it turned out we were still fairly inefficient at that acceleration of virality,” Remington said). The team also reviews story+tool combinations to share insights on successful ones with reporters and editors.

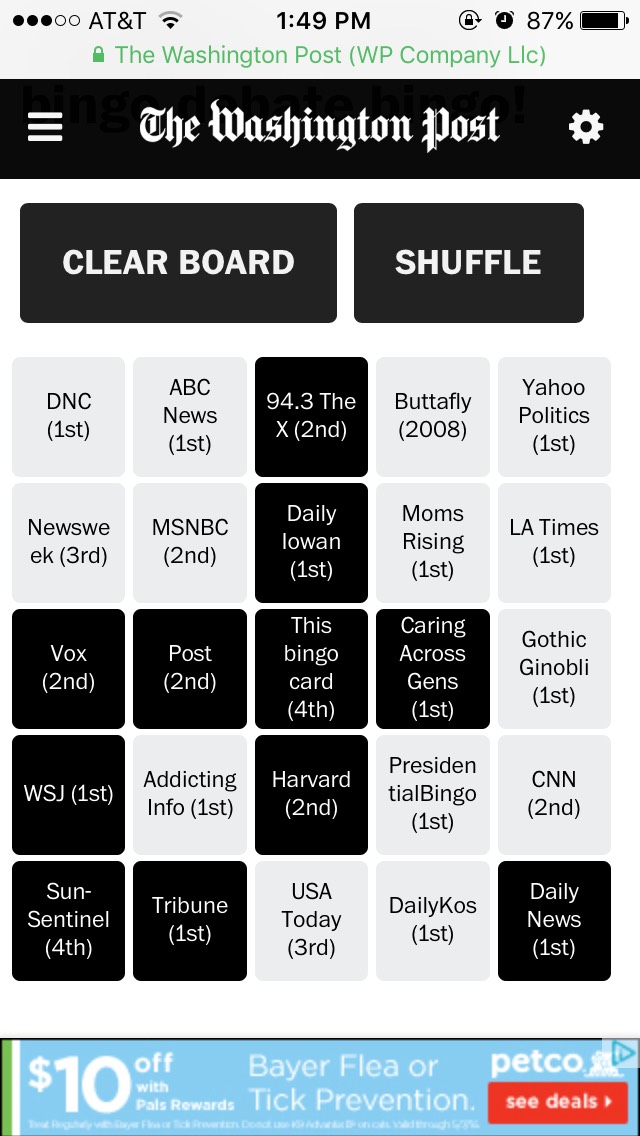

When is there enough newsroom demand for the group to build a reusable tool, versus just working with the graphics editors to build a one-off web app that doesn’t need to be maintained moving forward? An interactive bingo game, for instance, seems like a pretty limited use case (when Philip Bump assembled a Donald Trump debate facial expression bingo for The Fix, he warned: “Serious props to the Post’s tech team who put this little tool together, only for me to do the dumbest possible thing with it.”)“Starting last fall, we knew there was going to be an incredibly busy debate season coming up. There was an idea from the politics team that it would be cool to have an interactive bingo game. Every couple of weeks, or even less than that, there was going to be either a Democratic or a Republican debate, to say nothing of the town halls and everything else. So we figured, let’s build this out,” Remington said.

The team had about five weeks leading up to the first debate late last summer to whip the tool into working condition and make sure it was mobile-friendly (building the backend, writing and designing the frontend, building links into the Post’s content publishing system so the embedded feature would show up properly). “After the debate season abated, use of the tool went way down, but we anticipated that, and that’s okay. The bingo tool was an interesting threshold. If a tool is used twice ever, then that isn’t a great use of our time, but if it was used ten, twelve, then maybe it was.”

Having a newsroom partner with an editorial “launch case” is critical.

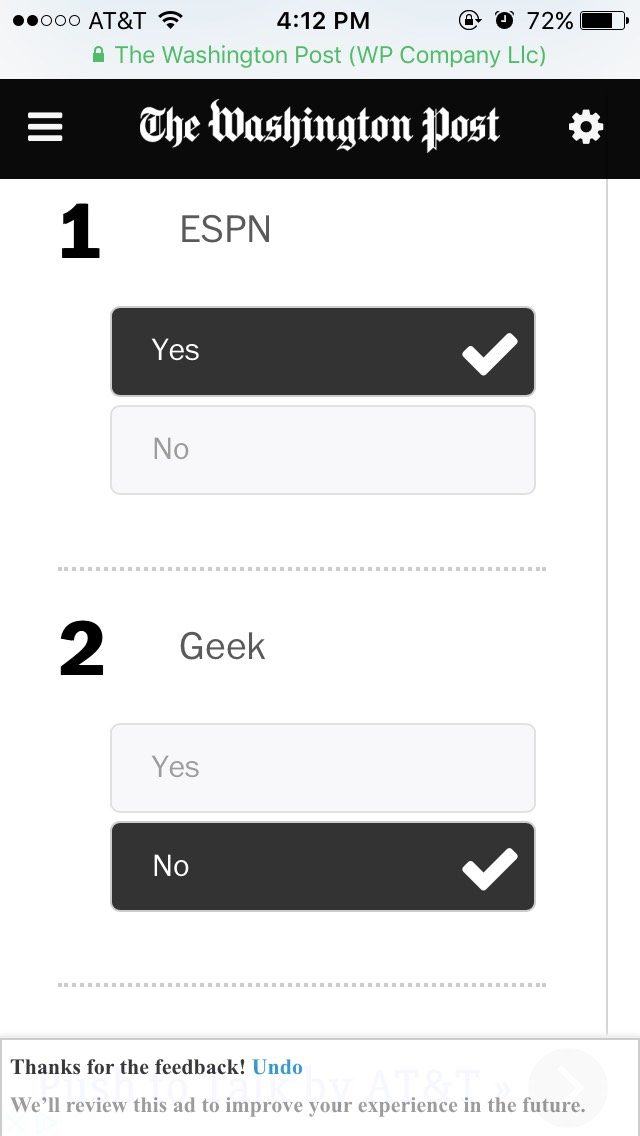

“We find people in the newsroom to be our launch partners. We have conversations within the newsroom. We might work with several desks, to make sure we’re not building a tool to only one desk’s specifications, but building something that has wider use throughout the newsroom,” Barber said. “We want something easy for Post journalists to go into, find, and embed within their stories, and to get the whole organization thinking: what’s the best way to get a user to understand and engage with a story?” There’s an open Slack room where anyone can ask for help or make requests or suggestions, and the team is rolling out a plug-in to make it easier for reporters working in WordPress to select and embed the tool they want to use in their story.Why not just use ready-made tools from a third party or tweak the many open source offerings out there? While the team does keep its “eyes open to what’s being developed elsewhere, so that we have as wide a view of what the industry is doing and what tech is already available,” often it’s just faster to build on its own code, and easier to customize. The Fact Checker team — which assigns political claims a certain number of “Pinocchios” based on their relative truthiness — wanted a tool that would also allow readers to be able to assign their own Pinocchios. The story tools team came up with a ratings feature, powered by much of the same code that it uses for its polls feature, and has been working with the features desk on other uses like restaurant or show ratings.

The story tools group also works closely with the Post’s graphics team, which will weigh in on whether a requested feature is something they can build as a standalone or something the story tools team might want to get involved in (that was the team that built a bookmarking tool to draw readers back to longer stories). Ideas for story tools can also come through the the Post’s New York City–based design and development office. The Notes feature (née Knowledge Map) originated there, from an idea to create reusable explainer snippets on specific words or phrases in complicated stories. It debuted last summer with stories on tech companies and the challenge of dealing with ISIS. The New York design shop began collaborating with story tools to work on automating the feature (the tool returned in February on the Post’s Zika coverage).Other features are in the pipeline, including a flow charts tool. “We’re trying to figure out how to structure the admin end,” Kastning said. “When people are creating a flow chart, do they need to come to the tool with a preconceived idea of how they want to illustrate a story through clickable steps, or should they need to play around more?”

“We had a different start, building ‘games.’ But those are still story tools! Everything we build is just a different way for journalists to tell stories,” she said.