Editor’s note: Hot Pod is a weekly newsletter on the podcasting industry written by Nick Quah; we happily share it with Nieman Lab readers each Tuesday.

Welcome to Hot Pod, a newsletter about podcasts. This is issue 108, published February 21, 2017.

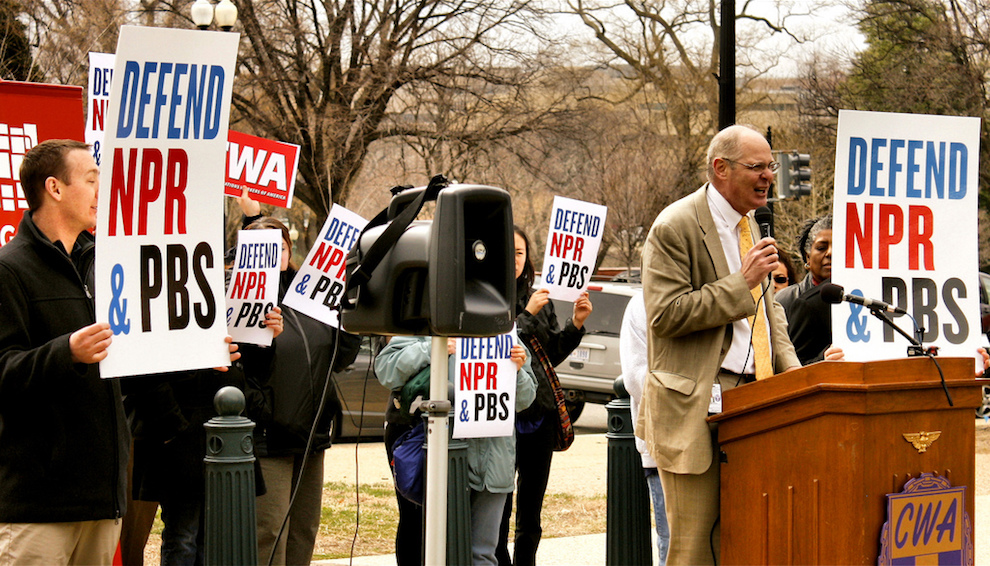

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting is now officially on a hit list of programs that the White House might eliminate, according to a New York Times article that led the site over the weekend, effectively pushing what was previously speculation — originated by a report from The Hill last month, which claimed that the Trump administration was considering privatizing the CPB — into an unambiguous news development.

I’ve highlighted this story a few times before, and while this specific development seems arguably incremental, it is nonetheless incredibly important to track given the depth of its consequences. Plus, there’s been a bunch of writing and side-stories that have emerged on this topic, which gives us enough material to piece together a clearer picture of what’s happening, why it matters, and why it bites.

Now, it should be noted that the public broadcasting system in general — and the CPB in specific, which serves as a key funding layer for NPR, PBS, and various public broadcasting stations across the country — have been consistent targets of cuts and criticism by conservatives. Personally, I’ve always been unclear on the precise reason for this; based on my reading, it appears to be some amalgamation of perceived liberal bias — a characterization that seems to be uttered with increasing synonymity with accountability media — and misuse of taxpayer dollars, never mind the public benefit and the paltry sums of savings such an elimination would entail. (For reference, CPB appropriations in recent years are around $445 million annually. And for further reference, government spending is projected to be $4 trillion this year.) This Currently Curious article from last November is a pretty good historical guide to the last time the GOP controlled the government, and over at Recode, friend-of-the-newsletter Dan Frommer pointed out how Richard Nixon once proposed halving CPB funding in 1969 — a few years after the CPB was formed. Despite those threats, federal support for the system has never seriously been compromised, and it is in this historical fact that fuels the beliefs of some that this simply won’t happen. But, as I’ve pointed out before, this is very much in an anomalous political environment, one where nothing seems off the table whether it’s a travel ban, or a wall previously thought to be a symbolic piece of campaign bravado, or a defunding of a federally supported public information system that improves the lives of millions.If the elimination of federal support were to take place, the consequences for the public broadcasting system would be catastrophic. According to a CPB-commissioned study by Booz & Company, cited by Media Matters and Current’s reporting on the issue, “there is no substitute for federal support of public broadcasting, and that the loss of federal support would mean the end of public broadcasting.”

The defunding of public broadcasting will be an unpopular measure. A survey commissioned by PBS, which was reported by Current, found that the majority of American voters oppose the elimination of federal funding for public television. Specifically, 73 percent of those surveyed oppose the proposed measure — which breaks down to 83 percent of Democrats, 82 percent of independents, and 62 percent of Republicans — while 76 percent of respondents want funding levels to be maintained or increased. (The survey made no direct mentions of public radio, but I reckon the study serves as a reasonable proxy for the broader public broadcasting system. And for reference, the survey study was conducted by both Democratic and Republican polling teams.)

The Times report notes that the list of eliminated programs could still yet change, which means that the public broadcasting system still has a bit more time to continue its preparations for cuts and/or lobbying against it — which is something that they’ve already been doing.

This is probably the point of the article where I’m supposed to bring up an opposing, or contrarian, view on the matter. That perspective comes from the libertarian magazine Reason, where Jim Epstein, a former WNET producer, makes the survival-of-the-fittest argument: He argues that government funding actually hurts PBS and NPR, and that the elimination of federal support would shock the system out of its broadcast-oriented dependencies and incentives towards online distribution. Which, you know, is a view that I understand conceptually (even if it’s a little reductive and certainly overly Pollyanna-ish). But the evolution argument always strikes me as hollow and inhumane, as it never really fully reckons with and takes responsibility of the human cost of the resulting layoffs, the organizational complexity attached to structural transitions, and the simple fact that evolution necessarily yields losers — which is fine if we’re talking about markets distributing doorknobs, but totally sucks for markets distributing public goods like civic-oriented news, emergency signals, and supplemental forms of public education. Look, I’m as critical about the public broadcasting system’s predisposition for inertia and its many, many, many problems as the next guy, but I’d much rather see a transition to the future that takes place under conditions of strength and volition, not one under unnecessary duress and survival.

A weakened public broadcasting system is bad, bad, bad. It’s bad in ways you already know, and it’s bad in countless ways you don’t. A recent episode in West Virginia is illustrative of the latter category. When West Virginia Governor Jim Justice — a Democrat — proposed eliminating state support for West Virginia Public Broadcasting — ostensibly to close a $500 million budget gap (cutting WVPB support would save $4.5 million), but maybe for a whole other reason that NPR’s David Folkenflik hinted at on Twitter — a statement published by Susan C. Hogan, chair of the Friends of West Virginia Public Broadcasting, and Ted Armbrecht, chair of the West Virginia Public Broadcasting Foundation, went over the various negative impacts of a debilitated WVPB: from the stuff you can probably guess, like the laying off of half their reporters and terminating a well-loved music program (long live Mountain Stage), to stuff you might not immediately consider, like how it compromises the operation of radio towers that facilitate the communication of first responders and how the loss of said music program would hurt tourism to the state. A loss in CPB support would incur the same effect for public broadcasting stations across the country, though the precise effects will vary based on their own specific configurations. Everyone will suffer in their own way, but everyone will suffer.

The West Virginia episode is also indicative of a whole other element to this story: It serves as an example of how the attacks on public broadcasting won’t just be coming from the White House; it can and will come from state leadership as well. The two developments are not unconnected — after all, the former sets the tone for the latter.

Yeah, sure, Epstein may well be right that pulling federal funding might lead to more efficient and innovative outcomes, but gains will be experienced unequally across all actors in the system — the bigger organizations in denser locations will likely thrive, while the smaller ones will likely not, and the system as a whole will almost certainly suffer. (See: the Internet and local newspapers.) And it is the integrity of the system, not any individual actor, that is so much more important at the end of the day. (See: modern democracy.)

And lest I forget this is a newsletter about podcasts, I’ll say this: A weaker public radio system is a weaker podcast ecosystem. Regardless of your feelings about public radio unfairly dominating the podcast narrative — and it has been pretty unfair, I’ll admit — it absolutely cannot be denied that the public radio contingent has represented a strong, validating pillar of an industry that often looks and feels like a chaotic mess. The term “wild west” has often been thrown about to describe the podcasting landscape, and while it is usually deployed with positive intent, the reality is that the whole thing largely resembles a “vast wasteland,” to crib from Newt Minow’s description of television back in 1961. (Hat tip to Joseph Lichterman’s spectacular historical account on Carnegie Commission on Educational Television’s 1967 report, which laid the foundation for the public broadcasting system we enjoy today.)

For all the crap you can understandably give public radio, it has undoubtedly done a lot to increase the podcast medium’s profile (increasing its appeal for both brand advertisers and audiences of all stripes), produced some great shows, and given us some truly great talent (all hail Anna Sale). I, for one, hope the system survives however this plays out.

Anyway, here’s Mr. Rogers.

Okay, that went way too long. On to the news.

iHeartRadio continues to burrow into the podcast space, signing a partnership with AudioBoom that will further expand the streaming audio company’s content catalog. This follows several podcast-related partnerships that iHeartradio has announced in recent months, including LibSyn, Art19, and NPR member stations.

As a reminder, the value proposition that iHeartRadio provides these podcast platform companies is theoretical access to the service’s reportedly large user base. iHeartRadio apparently has over 95 million registered users, but two caveats apply: (1) the exact number of monthly active users — the key metric — is still unclear, and (2) it remains to be seen whether partner podcasts can meaningfully benefit from the iHeartRadio user base. As any public radio member station that has attempted to convert broadcast listeners to podcast listeners can tell you (see the Knight Foundation’s recent podcast report, Point 1), conversion aspirations aren’t all that straightforward.

Related: Audioboom also announced a branded content partnership with SpikeTV to produce a discussion podcast companion for the latter’s upcoming six-part true crime series, Time: The Kalief Browder Story.

What’s up with Barstool Sports? I’ve previously not paid much attention to the company — which now sports several podcasts peppering the iTunes charts — and, frankly, I don’t know very much about it beyond the headlines off the trades: its 2016 acquisition by the Chernin Group, its aggressively male character, its largely sports-oriented content focus, its various controversies of the misogynist variety. I thought last week’s Digiday Podcast, which featured an interview with the company’s CEO Erika Nardini, serves as a helpful primer, and if you’re curious and confused about them as I was, do check it out.

Anyway, a press release hit my inbox last week that touted the company as “dominating” the podcast game, making the argument by listing the iTunes chart positions currently occupied by the company’s various podcasts. When asked, the marketing firm that distributed the release claims that the network enjoys 22 million downloads a month across all shows (by my count, it has 18 in the market at the moment).

The number strikes me as conspicuously high, and I’ve requested for more specific details on both downloads and the context of those numbers. (I haven’t heard back yet.) At the moment, it’s not immediately clear where the network hosts its shows — and therefore, how it counts its downloads — and whether it abides by the measurement standardization practices increasingly being adopted by the rest of the industry. For reference: If the numbers are precise and appropriate for actual apple-to-apple comparisons, that would mean the network effectively stacks up against HowStuffWorks, WNYC Studios, and This American Life/Serial as measured by Podtrac, which doesn’t measure the Barstool Sports group of podcasts.

Is that plausible? Sure. Is that the case? Let’s find out. I’ll let you know when I hear back.

Fusion is set to debut its first narrative show next month, Digiday reports. The show, titled Containers, will be hosted by editor-at-large Alexis Madrigal, and it will utilize an Oakland seaport as a prism through which various key issues like crime and immigration will be discussed. In other words, it’s The Wire season 2, but for non-fiction storytelling podcasts.

Note the mention of Panoply in the article, which is described to have “won out against a field of competitors for Fusion’s business.” I wonder who else was bidding?

Anyway, as the report establishes, Containers will be the Fusion Media Group’s first stab at a podcast that goes beyond the conversational gabfest-format that make up its current audio offerings, all of which emerge from the recently acquired Gizmodo Media Group (née Gawker). Interestingly enough, the group had dabbled with story-driven, narrative podcasts before: back in the Gawker era, Gizmodo once distributed Meanwhile in the Future, the original iteration of Flash Forward, which creator Rose Eveleth now operates independently.

Slate names June Thomas as new managing producer of podcasts, as Thomas announced on social media last week. She is a long-time member of the Slate family, serving as a culture critic for the site and the editor of Outward, its LGBTQ section, and a regular across the Slate podcast universe: she’s a host on Slate’s Double X podcast with Hanna Rosin and Noreen Malone, and a frequent guest on the Slate Culture Gabfest.

The announcement came a few days after news of Slate laying off staffers broke last week. And a bit more detail on that front: According to this pretty brutal CJR article, among those let go was Mike Vuolo, a senior producer with the company and WNYC alum who also, up until last summer, cohosted the network’s language podcast, Lexicon Valley, with On The Media’s Bob Garfield.

Thomas starts her new role on February 27.

Gimlet loses a producer to The New York Times: Larissa Anderson, who served as a senior producer on Undone, will now work on developing and running narrative podcasts at the Gray Lady. Her title there is “editor and senior audio producer.” And in case you’re tracing the timeline: Gimlet announced that it wasn’t renewing Undone for a second season in mid-January.

Signaling. One of the more technical questions that’s interesting (to me, anyway) coming out of the recent discussions over “fake news” — which is really a discussion about trust, credibility, and the decentralization of information and power — is one that distinctly strikes me as a problem of design: In the enterprise of cultivating trust, how do you convey positional context, whether an editorial piece has opinion-based elements baked in or whether it’s meant to be journalistically or somewhere in between, in a way that’s clear and efficient? (Provided that making such things clear is important to you, of course.)

It’s a hard enough question to answer on the web, print, television, or within the endless stream of social media feeds, but it seems a lot trickier within the current culture surrounding audio content, given its primary value proposition of being a unique source of intimacy by way of authenticity.

The problem was raised very briefly at a Yale event last week that featured Scott Blumenthal, deputy editor at The New York Times’ interactive news desk. (One of the benefits of living in New Haven, a university city: access to free student events — and free snacks!) An attendee had brought up The Daily, the Times’ recently launched daily morning news audio brief, and raised concerns over whether the podcast’s breezy conversational nature runs the risk of coming off as editorializing. I don’t personally share this interpretation of the brief, but I can definitely see the concern: host Michael Barbaro is certainly chatty, and I suppose we somewhat find ourselves now living in a cultural environment that increasingly views personality as a direct function of ideology. (Maybe that’s always been the case, and it’s only being recognized as a problem now.)

So, how do you convey your context? I’ll be thinking this through for a while, and I’ve been recalling some approaches to this problem that I’ve seen in the past. Sometimes it’s through the use of an explicit disclaimer delivered through scripting; an example of this can be found in With Her, that Hillary Clinton podcast, in which host Max Linsky deliberately establishes the fact he isn’t operating as a journalist — thus contextualizing the show as, essentially, a piece of political advertising. Sometimes it’s done purely through the scripting and tone of the show; Slate’s The Gist is a good example of a news-oriented podcast that largely exists as an op-ed column, while the oft-criticized “public radio voice” pervading public media newscasts is constantly described as a tool to cultivate a sense of journalistic neutrality. And sometimes it’s just a matter of being clear and unified with the branding, as with the conservative Ricochet podcasts. All these approaches are difficult to execute in and of themselves, but I imagine it’s exponentially more difficult to convey differences in context within individual episodes — say, when you switch from a reported segment to an opinion segment.

This problem seems to disproportionately trouble journalistic podcasts above all, which makes sense, as those shows are the ones under the greatest scrutiny and possess the highest burden of responsibility. And it seems to me that the problem most vibrantly expresses itself when straight-news programs seek to derive the benefits of “authenticity” and “intimacy” associated with the on-demand audio medium that more personality-driven programs seem to enjoy without much cost. Then again, I imagine the latter experiences similar difficulties if it aspires to benefit from emulating the former.

I’m curious to hear what y’all think. Hit me up.

Anyway, before I forget: The Daily is so, so good, and so smart in its use of music and tone, and its short length.

Bites: