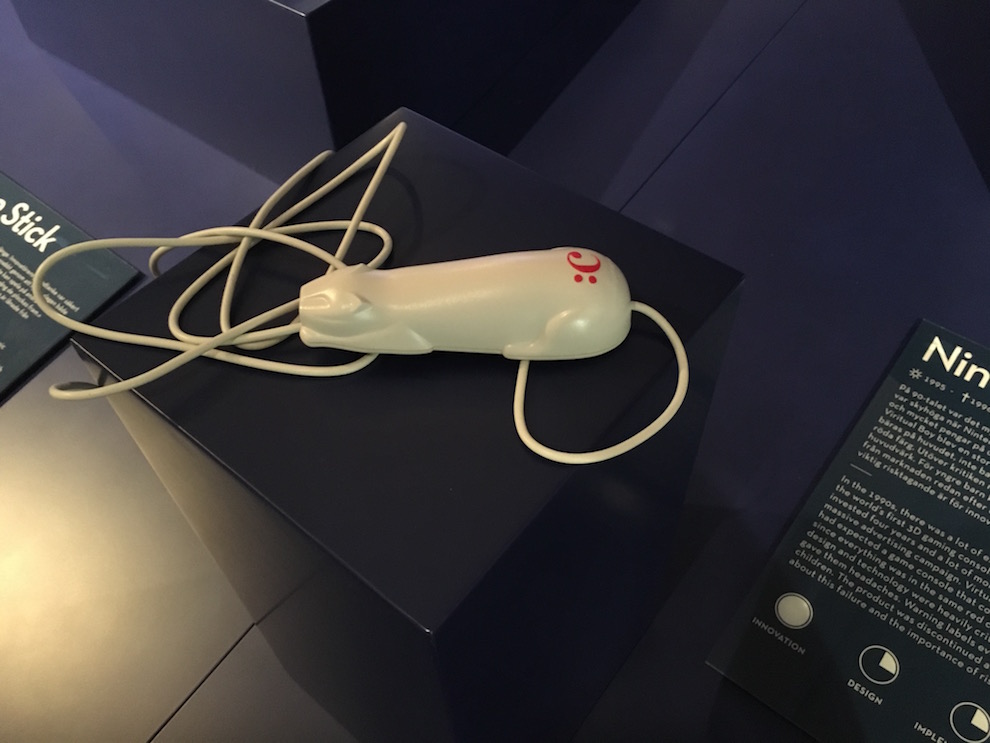

HELSINGBORG, Sweden — In the media world, few products have come to symbolize digital failure more than the CueCat, the feline-shaped, barcode-scanning device that flopped at the turn of the millennium, costing magazine and newspaper publishers tens of millions of dollars.

More than a decade later, a castaway CueCat sits atop a pedestal at a new Swedish museum, where it is memorialized as an “epic dot-com failure.” But this is no snarky exercise in innovation schadenfreude — the Museum of Failure, which opened June 7, features about 70 doomed products and services with the goal of encouraging a sense of appreciation for failure’s essential role in the entrepreneurial process.

“Failure is an important part of being innovative,” museum manager Emelie Andersson told me when I visited the museum last week. Innovation is inherently risky, Andersson said, and most new products fail. What’s key is learning from your missteps: “Companies need to admit that failure is a part of the work. And if you can fail small, you can avoid the big failures.”

In addition to the CueCat, which publishers sent out for free in hopes of spurring subscribers to shop more online, the museum features an assortment of ill-fated gadgets that, despite their stumbles, helped pave the way for future innovation.

Consider the Newton: Released by Apple (prematurely, in hindsight) in 1993 as the company’s first personal digital assistant, the device was plagued by problems with handwriting recognition to the point where it was mocked on The Simpsons. When Steve Jobs returned to Apple as CEO in the late 1990s, he killed the Newton, but that move freed up engineers to work on new mobile technology that eventually would lead to the iPhones so many of us carry in our pockets today.

Apple’s ability to learn from failed mobile experiments might even bode well for Google Glass, another of the museum’s not-so-ancient artifacts. A pair of the once-vaunted smart glasses rests stylishly atop a mustachioed mannequin head, lampooned by exhibit text as “nothing more than an expensive prototype.” But if Google ultimately learns from Glass’s failure, who knows what contraptions might be perched on our noses 10 years from now?

Not every exhibit has a silver lining. Reflecting the Silicon Valley mantra to “fail fast” and adapt, some of the museum’s gizmos failed so fast, only the devoted tech watcher may have ever heard of them: the Modo (a paging device with city entertainment listings and coupons), the Microsoft Kin (a mobile phone that lacked basic smartphone functionality), TwitterPeek (a single-use device that only displayed a tweet’s first 20 characters) and the Apple Pippin gaming console (three times as expensive as a Nintendo 64).

There are plenty of non-tech duds, too: green Heinz ketchup, Bic “For Her” pens, new Coke, and Donald Trump’s Monopoly-esque board game (Trump Vodka, I’m told, is on the way).

Organizational psychologist Samuel West, the museum’s curator, explains to visitors in a welcome message that he collected the items out of frustration after years of “reading and hearing the same boring success stories.”

“All these success stories are alike,” West says. “It is in the failures that we find interesting stories that we can learn from.”

A few of the museum’s items seem a bit off the mark. Blockbuster Video, for example, may not have been nimble enough to avoid market disruption by ditching its late fees and fending off Netflix, but it was no flash-in-the-pan failure, enduring for nearly three decades. Still, any technology enthusiast will be mesmerized for a couple hours while taking a nostalgic stroll through the museum, which also offers a pointed lesson or two for modern journalism.

One exhibit takes the global media to task for failing to sniff out No More Woof, an absurd Swedish crowdfunding campaign for a mind-reading headset that would translate your dog’s brain waves into human words. Journalists published fawning stories that fed the hype while the purported innovators accepted donations for a product that never delivered. As the museum puts it, “this is a great example of how crowdfunding campaigns capitalize on people’s blind hunger for innovation by promising the impossible.”

And then there’s the CueCat, which media executives envisioned as a game-changing tool for readers who would: 1) spot bar codes in print ads; 2) carry the printed material to their PC; 3) use the CueCat to scan the code and — voila! — eagerly explore supplemental content that appeared on their computer screens.

The concept, of course, didn’t correspond with the actual reading habits of human beings, adding up to an expensive mistake for publishers including Forbes, Wired and The Dallas Morning News (my former employer, although I didn’t work there at the time). In a scathing Wall Street Journal review, Walt Mossberg called the CueCat’s premise “unnatural and ridiculous.”

“I think the learning story there is that you should think about the consumer when you develop a product, because nobody wanted to read the magazine in front of the computer,” Andersson said. “I think that’s a really big part of it — having the consumer in mind and thinking not only, ‘Is this a good product?” but also thinking about how it will be used and what the consumers will see it as.”

The museum costs 100 Swedish krona (about $12) and is open daily through September in Helsingborg, a southern Swedish city across the Øresund Strait from Denmark.

Jake Batsell is an associate professor of journalism at Southern Methodist University, where he teaches digital journalism and media entrepreneurship.