We haven’t seen much data so far on exactly how bad the spread of fake news is across the European Union. But some new research from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism might help.

In a report entitled “Measuring the reach of ‘fake news’ and online disinformation in Europe” released Wednesday evening, authors Richard Fletcher, Alessio Cornia, Lucas Graves, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen write that “with the partial exception of the United States (e.g. Allcott and Gentzkow 2017; Guess, Nyhan, and Reifler 2018; Nelson and Taneja 2018), we lack even the most basic information about the scale of the problem in almost every country.” (Nielsen is a member of the European Commission panel on fake news and online misinformation, and he’d previously called attention to the lack-of-EU-research issue in a number of tweets.)

The paper focuses specifically on France and Italy. The authors looked at “a starting sample of around 300 websites in each country that independent fact-checkers have identified as publishers of false news,” then narrowed them further.

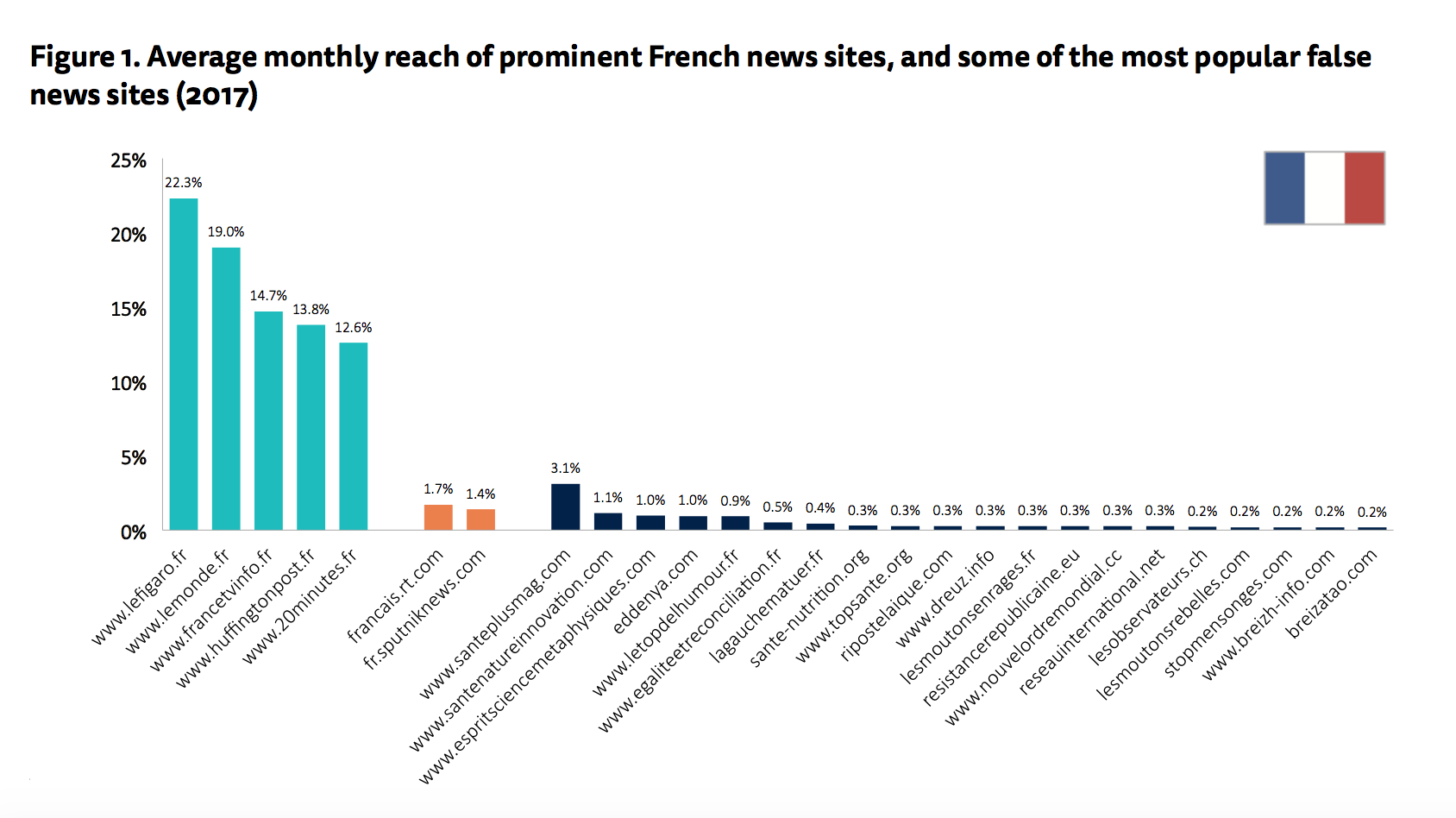

The findings are largely reassuring, though preliminary: These sites seem to have tiny reaches compared to legitimate news sites, and audiences spend much more time with the legitimate sites than the fake news sites. In almost all cases, fake news sites didn’t generate nearly as many Facebook impressions as legitimate brands, though there were a couple exceptions. The authors stress that more research is needed.

None of the false news websites we considered had an average monthly reach of over 3.5 percent in 2017, with most reaching less than 1 percent of the online population in both France and Italy. By comparison, the most popular news websites in France (Le Figaro) and Italy (La Repubblica) had an average monthly reach of 22.3 percent and 50.9 percent, respectively;

The total time spent with false news websites each month is lower than the time spent with news websites. The most popular false news websites in France were viewed for around 10 million minutes per month, and for 7.5 million minutes in Italy. People spent an average of 178 million minutes per month with Le Monde, and 443 million minutes with La Repubblica — more than the combined time spent with all 20 false news sites in each sample;

Despite clear differences in terms of website access, the level of Facebook interaction (defined as the total number of comments, shares, and reactions) generated by a small number of false news outlets matched or exceeded that produced by the most popular news brands. In France, one false news outlet generated an average of over 11 million interactions per month — five times greater than more established news brands. However, in most cases, in both France and Italy, false news outlets do not generate as many interactions as established news brands.

The starting sample of 300 French sites came from Le Monde’s Décodex; the Italian sites were compiled using two Italian fact-checking sites, BUTAC and Bufale, and from an Italian hoax-busting site called Bufalopedia. From there, there was further narrowing: The team excluded satirical sites (which have their own category in Décodex) and also included, for comparison, Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik, the two Russian state–backed sites that have featured in European discussions of disinformation.

“Following this process, we were left with 38 false news websites in France and 21 in Italy,” they write, “allowing us to estimate average monthly reach and average monthly time spent for many of the most popular online disinformation sources in 2017. We present data here for the top 20 false news sites yielded by our search in each country.”

In France, the most popular fake news site was Santé+ Magazine, “an outlet that has been shown by Les Décodeurs to publish demonstrably false health information,” which reached around 3 percent of the French online population.”

Similarly, “in Italy, the most widely-used false news website in our sample — Retenews24 — reached 3.1% of the online Italian population.”

In both countries, the researchers found overlap between the use of fake and legitimate sites:

If we consider desktop use only (comScore is not able to provide figures for mobile overlap in France or Italy), we see that 45.4 percent of Santé+ Magazine users also used Le Figaro in October 2017, and 34% used Le Monde. This aligns with previous research showing, despite their size, audiences for niche outlets often overlap with the audiences for more popular mainstream brands (Webster and Ksiazek 2012)…

There is also evidence of sizeable audience overlap between false news sites and news sites in Italy. To take one example, in October 2017, 62.2 percent of Retenews24 users also visited the website of Il Corriere della Sera, and 52.3 percent used La Repubblica.

When it comes to Facebook interactions there may be less reason to be optimistic: “Particularly in France, some false news outlets generated more or as many [Facebook] interactions as news outlets.”

Overall, though, the authors see some preliminary good news: In Italy and France, as in the U.S., “our analysis of the available evidence suggests that false news has more limited reach than is sometimes assumed.” But remaining questions (for instance: “We have not considered the potentially ‘long tail’ of false news access. If there are many other sites that publish false news, and the degree of overlap between their audiences is low, it may be that their combined reach is greater than that implied by the low individual reach figures. This matters even more if false news sites are reaching people that news sites do not”) should be researched further.

The full report is here.

66 comments:

Hi there! Do you know if they make any plugins to assist with SEO?

I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good gains.

If you know of any please share. Thank you!

Hey there! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an established blog.

Is it very difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not

very techincal but I can figure things out pretty quick. I’m thinking about creating

my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any ideas or suggestions?

With thanks

Nice post. I used to be checking continuously this weblog

and I am inspired! Very useful information specially the final phase :

) I maintain such info a lot. I used to be seeking this

certain info for a long time. Thank you and best of luck.

The design profession became competent after World War II.

From the 1950s onwards, shelling out for the home increased.

Interior design courses were established,

requiring the publication of textbooks and reference sources.

Historical accounts of interior designers and firms distinct on the decorative arts specialists were presented.

Organisations to manage education, qualifications, standards and practices, etc.

were established with the profession.[18]

Interior design was in the past seen as playing a

second role to architecture. It also has numerous connections with design disciplines, regarding

the work of architects, industrial designers, engineers, builders,

craftsmen, etc. For these reasons, the us govenment of home design standards and qualifications was often utilized in other professional organisations that involved design.[18] Organisations like the Chartered Society of

Designers, established in the UK in 1986, and also the American Designers Institute, founded in 1938, governed

various parts of design.

It had not been until later that specific representation to the interior

design profession originated. The US National Society of Interior Designers

was established in 1957, within the UK the Interior Decorators and

Designers Association was established in 1966. Across Europe, other organisations such as The Finnish Association of Interior Architects (1949) were being established along with

1994 the International Interior Design Association was founded.[18]

Ellen Mazur Thomson, author of Origins of Graphic Design in America (1997),

determined that professional status is achieved through education, self-imposed standards and professional gate-keeping organizations.[18] Having achieved this, design became an acknowledged profession.

Hmm it appears like your blog ate my first comment (it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I wrote and say,

I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new

to the whole thing. Do you have any tips and hints for beginner blog

writers? I’d definitely appreciate it.

WOW just what I was searching for. Came here by searching for nhà

thầu xây dựng

WOW just what I was looking for. Came here by searching for cty

xây dựng

Why viewers still use to read news papers when in this technological globe everything is accessible on web?

By the turn from the 20th century, amateur advisors and publications were

increasingly challenging the monopoly how the large retail companies had on home design. English feminist author Mary Haweis wrote a few widely read essays inside the

1880s where she derided the eagerness in which aspiring middle-class people furnished their houses based on the rigid

models accessible to them from the retailers.[10] She advocated the consumer

adoption of any particular style, tailor-made to anyone needs and preferences with the customer:

“One of my strongest convictions, and one from the first canons of fine taste, is our houses, just like the fish’s shell and also the bird’s nest, must represent our individual taste and habits.

The move toward decoration being a separate artistic profession, unrelated towards the manufacturers and retailers, received an impetus while using 1899 formation from the Institute of British Decorators; with John Dibblee Crace becasue it is president, it represented almost 200 decorators about the country.[11] By 1915, the London Directory listed 127 individuals trading as interior decorators, ones 10 were women. Rhoda and Agnes Garrett were the primary women to coach professionally as decorators in 1874. The importance of their focus on design was regarded back then as on the par your of William Morris. In 1876, their work – Suggestions for House Decoration in Painting, Woodwork and Furniture – spread their tips on artistic interior planning to a wide middle-class audience.[12]

Every weekend i used to pay a quick visit this site,

as i want enjoyment, since this this web site conations really nice funny material

too.

We’ve seen CPUcoolers sportting LCDs earlier

than, but not a loot wth GPUs. Measuring 323 x 158 x 60mm (LxWxH), it’s a beefy

csrd tto slot into your Pc, so you positively wish to ensurre you don’t have your CPU cooling pipes close to

this GPU orr every other cabling. The company’s new Vacujm Cooper

Plate know-how helps to attract heat away from the card

as properly, through the use of a particular chamber containing cooling liquyid and copper

powder. Colorful did embrace a particular holder which you’ll screw onto the again off the

card to help it higher in a horizontal setup.

As with the previous era, there’s also a USB-C port and an RGB

header at the again of the card. You can use the incluhded RGB header cable to

attach the card directly to your motherboard in order that it

syncs with the remainder of your RGB lighting, whiloe the USB-C port musst be linked

to a spare USB header on your motherboard with the included

cable. The EGASS platform may be deployed to your personal

servers to ensure that your answer is fully hosted and managed

in-home.

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d certainly donate to this excellent blog!

I suppose for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and

adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I

look forward to fresh updates and will talk about this website

with my Facebook group. Talk soon!

It granted regulation enforcement businesses, just like the FBI, new powers within the title of national security.S. The European powers had management of different components of Asia by the early twentieth century, reminiscent of British India, French Indochina, Spanish East Indies, and Portuguese Macau and Goa. Undoubtedly there is no such thing as a place like Asia with regards to the matters of love and hospitality. Doug Paal, director of the Asia Program on the Carnegie Endowment for Worldwide Peace, mentioned he believed the U.S. Customs and Border Safety, U.S. These businesses include U.S. With generous funding from the U.S. The Nationwide Regulation Enforcement Officers Memorial displays the names of these fallen officers on its partitions. The museum houses more than 20,000 objects associated to legislation enforcement. In the United States, regulation enforcement officers have the authority to seize assets from any person they suspect of committing against the law. Before he turned the twenty sixth president of the United States, Teddy Roosevelt was a deputy sheriff in North Dakota.

Whereas the Fiat is not utilized in North America, it’s a preferred selection in Europe for Italian police officers who often need to navigate slim streets. For the western single men, courting Asian lady and marrying Asian women should be a good alternative. If you are aiming for communication – they are an excellent choice. Intercultural communication is nice for a lot of reasons. But you will notice that your Asian lady may be very versatile each in communication and in terms of love if she becomes your girlfriend. The 31-12 months-old’s parents, like many South Asian immigrants, had an organized marriage. A few of the most effective Asian nations for Western guys to look for brides include the Philippines, China, Vietnam, South Korea, Japan, and Thailand. COLUMBIA, South Carolina (AP) – Desperate for relief after years of agony, Jim Taft listened intently as his ache administration doctor described a medical system that would change his life. In an effort to be thought of for police work, candidates must move a background investigation, psychological screening and medical exam. However, the officers would not need to make an arrest with the intention to confiscate property. To make things worse, he has a run-in with the aloof Queen, who is the Wild’s League tournament champion.

While many states have a statewide law enforcement agency known as state police or highway patrol, Texas does issues just a little in another way. Since 2015, the people of the United States have honored law enforcement officers on Jan. 9. One instructed way to show your support and appreciation is to put on blue clothing. Law enforcement officers [url=https://about.me/idateasia]idateasia[/url] use digital management units in potentially violent conditions that require some type of pressure. In October 2001, President George W. Bush signed the Patriot Act into regulation following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. On September 11, 2001, 72 officers died while serving their metropolis in the wake of the 9/eleven terrorist assaults. As of 2017, New York City has misplaced 833 law enforcement officers in the line of duty. However occasions like shootouts prompted legislation enforcement to invest in semiautomatic pistols as their daily handgun. At the federal level, the Division of Justice oversees regulation enforcement. Positioned in Judiciary Sq. in Washington D.C., the National Law Enforcement Museum goals to teach the public about regulation enforcement by giving civilians a possibility to “stroll within the sneakers” of a legislation enforcement officer. Businesses throughout the Department of Justice embody the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives.

National Legislation Enforcement Museum located? Along with law enforcement, courts, and corrections work collectively to maintain the criminal justice system operating. Your bride can sustain a conversation on any subject, making her the proper companion for occasions. He was scouted to go to NFL for his skillset, making him the first British rugby player to transfer over to the NFL. By our estimates, men making between $20,000 and $50,000 can efficiently find mail order spouses. However in case you are devoted enough, you can find a couple of girls. You’ll find the answers to those and lots of other questions in this information. Does speaking in public make you shy, effectively, start going out more and you’ll overcome it. Sure cultural stereotypes make all Westerners assume Asians are all the same. There are about 197 international locations in the world proper now, and 151 of them are flying a flag that features not less than some crimson somewhere in it. In Western, there are particular stages of dating relationships earlier than they enter into precise critical relationships. When relationship an Asian lady, just remember to not be too overconfident. The primary reason why Westerns need to order an Asian bride is an Asian beauty.

Quality articles is the crucial to invite the visitors to go

to see the web page, that’s what this site is providing.

Excellent way of explaining, and good paragraph to take facts regarding my presentation focus,

which i am going to convey in college.

Hurrah! After all I got a web site from where

I can really get useful information concerning my study and knowledge.

Trackbacks:

Leave a comment