Internet penetration in China is at around just under 56 percent, according to a report released this year by the Chinese internet administrative agency CNNIC, which means there were around 772 million internet users in the country as of last December (and 753 million mobile internet users). These numbers have surely only grown since. (China’s still well below the U.S.’s internet penetration of 89 percent, though China’s connected population is well over twice the entire population of the U.S.)

A new China Internet Report out this week was compiled jointly by 500 Startups, the South China Morning Post (SCMP), and SCMP’s China tech site Abacus, and it offers fresher numbers illustrating the reach and ambition of Chinese tech companies, the aggressive influence of the Chinese government, and the behaviors and preferences of Chinese internet (well, let’s just basically say mobile phone) users. In a country of more than 1.4 billion people and no access to U.S.-born giants like Facebook, WhatsApp, or Google (or news sites like the Alibaba-owned SCMP, or The New York Times), local companies that have played nice with authorities have been able to thrive. I’ve picked out just a few numbers from the report, around short-form and streaming video and social and messaging apps, but you can download the full set of slides for yourself here.

The top companies in several major industries, in China versus in the U.S. China Internet Report 2018, pg. 4.

Three companies dominate the internet space, from media to gaming, financial technologies to artificial intelligence, education to autonomous vehicles. There is no online sphere where Baidu (you may know it best for its search engine), Alibaba (China’s e-commerce and technology behemoth), and Tencent (which controls all-purpose messaging service WeChat) aren’t involved, whether that’s by building their own products directly or acquiring or investing in other companies, including many well-known companies outside mainland China: Uber and Lyft, Snap, Cloudfare, Taboola, the list goes on. You can filter through this full list by company and sector over at Abacus.

Most Chinese smartphone users are watching shortform video on various short video apps. Time spent watching shortform video grew by 323 percent between December 2016 and December 2017 (as a percentage of total time spent on mobile internet activity). Messaging is the most prevalent mobile internet activity, but the percentage of mobile internet time spent there actually declined last year, according to the report. The same three major companies above also own the top platforms in the online (not shortform) video space.

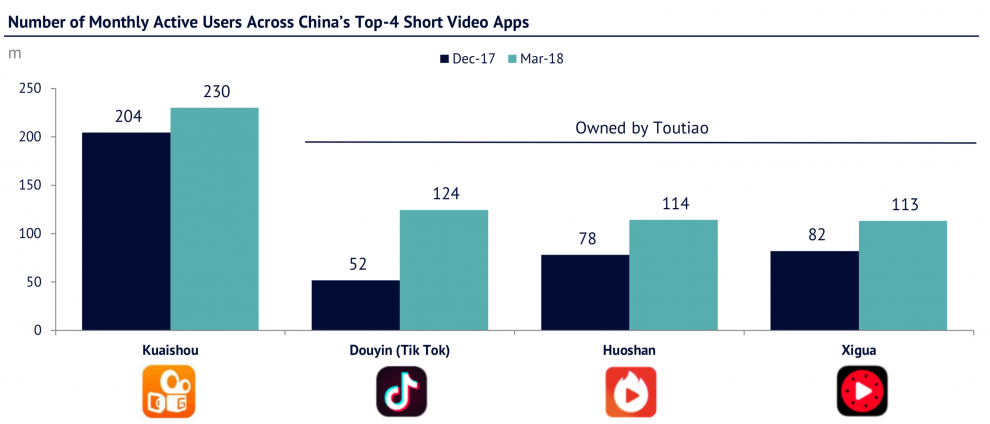

MAU for the top four shortform video apps in China. China Internet Report 2018, pg. 31.

An estimated 600 million people in China “are actively using short video apps” as of March of this year. Four main apps dominate that ecosystem, three of them owned by the personalized news app Toutiao. If you haven’t experienced any of these apps, know that a lot of the videos on the platforms are the familiar internet fare of people livestreaming themselves doing stuff. Kuaishou, the most popular shortform video app in China, has risen to the top in large part because of its focus on growing a user base beyond China’s largest “top tier” cities like Beijing and Shanghai. Despite the dominance of a few apps, competition in the livestreaming video space is fierce. One of my favorite illustrations of this (U.S. on the left, China on the right):

(Sanchez) Wang Jiapeng's #ISOJ2017 slide shows the different live streaming apps in China, compared to US. pic.twitter.com/OW3v6bQ4EY

— Robert Hernandez (@webjournalist) April 21, 2017

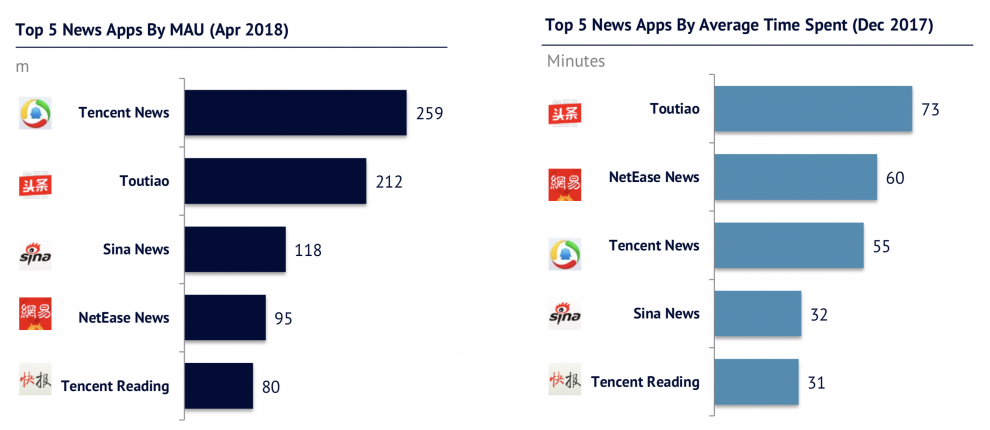

Most people in China get their online news through two platforms, Tencent News and Toutiao. An average user spent more than 73 minutes per day in Toutiao as of December 2017. Toutiao, interestingly, is starting to publish content from BuzzFeed, but overall I’m not totally sure about this “news” classification — most of what I’ve gotten when I check out my feed on Toutiao recently has been video of people making sculptures out of packets of instant ramen or fantasy World Cup lineup montages.

Toutiao and Tencent are the top apps for online news in China. China Internet Report 2018, pg. 34.

Tencent’s WeChat, though, is the undisputed ruler among mobile apps in China, now with around 1.04 billion monthly active users. Weibo, a Twitter-like platform that’s grown rapidly in the past year, has around 411 million monthly active users.

Many of these companies are in a delicate with the Chinese government over censorship of content on their platforms: Regulators ordered Toutiao to shut down its joke-sharing app over “inappropriate content,” which led to the company’s founder issuing a public apology and pledging to hire 4,000 additional in-house content moderators, bringing its total number to 10,000 (Facebook, with a much larger global user base, will have around 8,750 after a hiring spree). A top shortform video app, Kuaishou, was most recently in trouble for allowing content featuring teen moms. Potentially politically charged content regularly disappears, searches for key terms are disabled, and influential users are blocked on WeChat and Weibo.

An estimated 78 million rural internet users access news from three major news apps at least once a month. Internet penetration in rural areas of China had grown to 35 percent as of 2017, up from just seven percent a decade before.

The internet’s impact on rural China. China Internet Report 2018, pg. 16.