As a senior editor at The Philadelphia Inquirer, Daniel Rubin writes a daily newsletter with links to 10 “Hey, Martha!” articles — some on Philly.com, some on other news websites. The newsletter is a labor of love, Rubin said, and he kept it going even during a recent vacation to Ireland.

Scouring the web for newsletter fodder from a hunting lodge in Connemara, Rubin clicked through the privacy consent forms that the European Union now requires online publishers to present to visitors. No problem — until he read that Jonathan Gold, the Pulitzer-winning restaurant critic for the Los Angeles Times, had died.

“I went to the paper’s site to gather some of his articles and reviews and the paper’s obit, but they blocked me from even their homepage,” Rubin recalled.

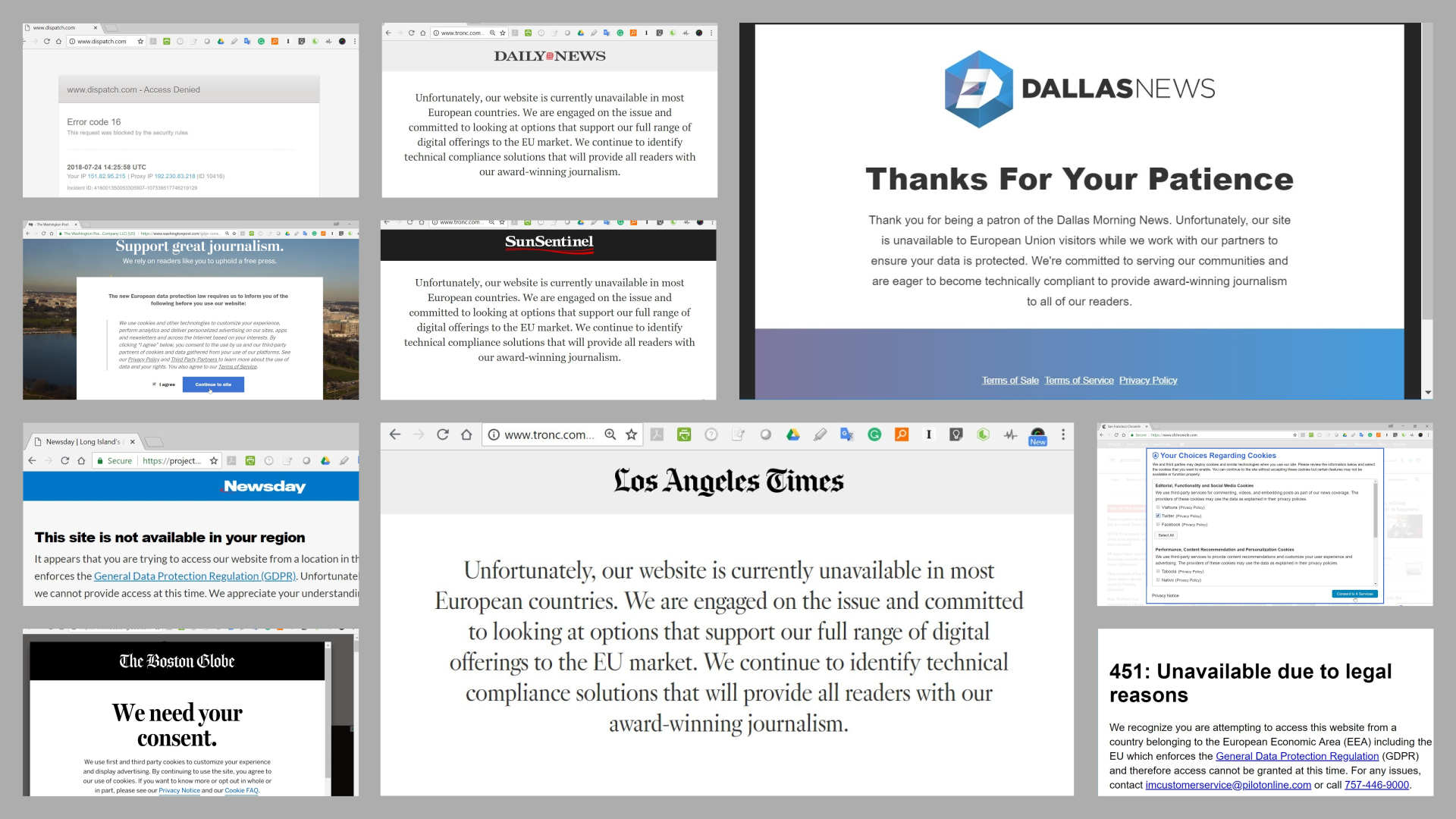

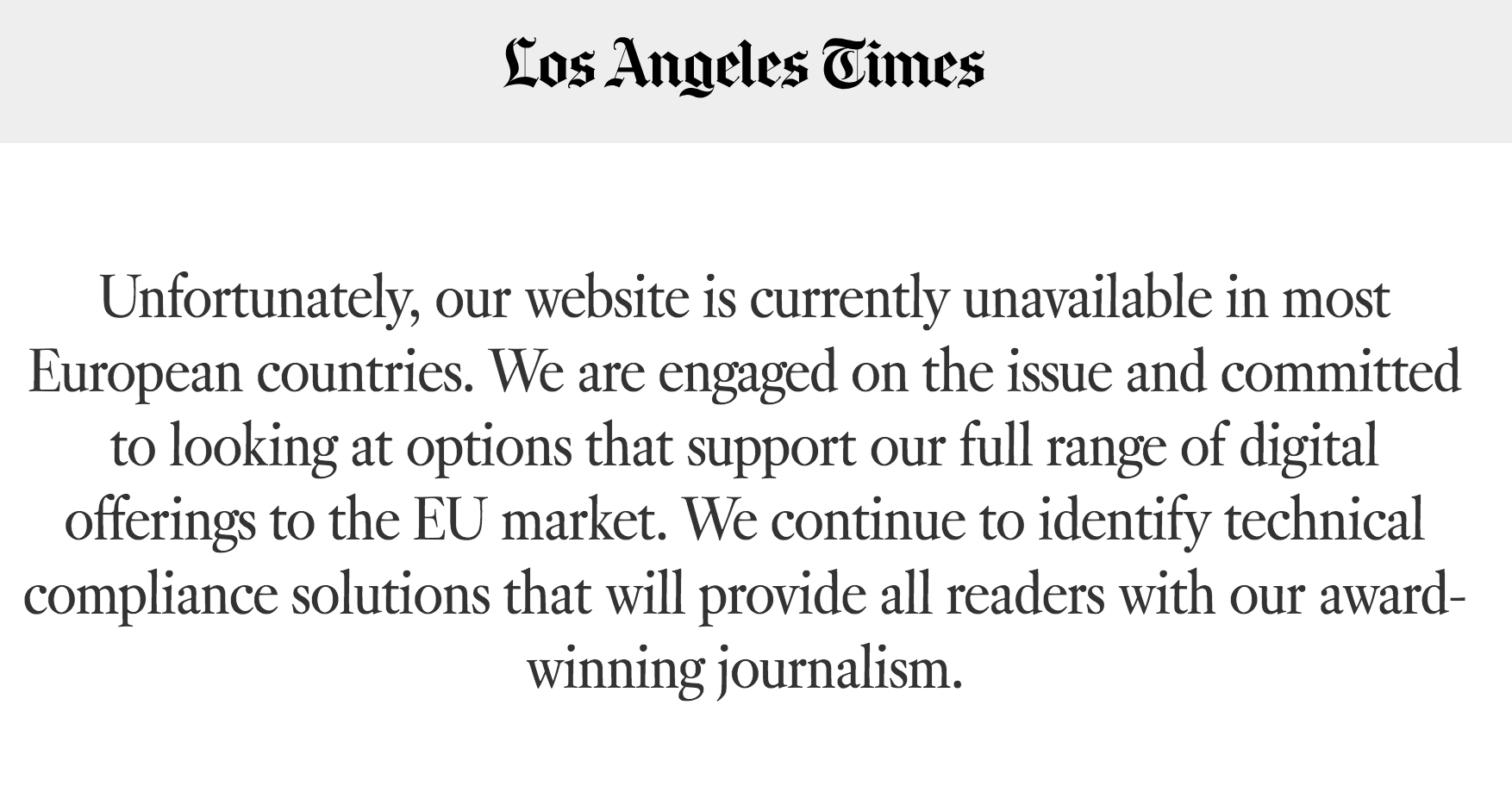

That’s because latimes.com has not complied with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, which took effect May 25. Instead, people accessing the site from Europe are routed to this notice.

More than two months after the GDPR took effect, hundreds of U.S. news websites — including digital properties operated by Tronc, Lee Enterprises and GateHouse Media — are unavailable in Europe, frustrating many American tourists, business travelers, and ex-pats as well as Europeans interested in news from the States.

“Usually, your media is seen as an example for ours. I think is safe to say that, in Portugal, there’s a big community of people that not only reads the Portuguese media but reads the U.S. press as well on a daily basis,” said Flávio Nunes, a journalist in Lisbon.

He was ticked when he tried to follow a tweet to a Los Angeles Times story on July 22. Nunes knew Tronc had missed the deadline to comply with the GDPR, but he figured that was a temporary oversight.

“I was surprised when I saw that, a couple of months after, they’re still blocking our access,” Nunes said. “It’s crazy because Europe is a massive market. We have over 500 million people living in the EU.”

James Longhurst, who teaches history at the University of Wisconsin, La Crosse, subscribes to his hometown newspaper, the La Crosse Tribune. While in Germany for an academic conference this summer, he was stymied in accessing the paper online.

“I found it very strange that the Tribune had essentially changed the global internet into an intranet, only available for local use,” Longhurst said. “It’s just amazingly parochial — a pretense that the rest of the world doesn’t exist and that people in the rest of the world wouldn’t have any access or interest in local news.”

Since May 25, scores of social media postings have complained that certain U.S. news sites were unavailable in Europe. Some blamed the EU.

I'm in Europe trying to read news back home and I'm getting blocked from U.S. news sites because of #GDPR. Thanks, Europe. #balkanization

— Jeff Jarvis (@jeffjarvis) July 12, 2018

But most postings blamed the media companies.

Dear American newspapers (especially the @latimes, I'm looking at you), please get to grips with GDPR before the next Ice Age, so that European readers can look at your websites again.

— Dr Nell Darby (@nelldarby) July 24, 2018

Mark A.M. Kramer, a Baltimore native studying at the University of Salzburg, has a subscription to the Los Angeles Times but can’t access the paper’s website from Austria.

“I have lived two decades in Europe in various locations and have always kept in touch with local U.S. news through online subscriptions,” Kramer said. His advice to blocked news sites: “Think global, cover local. You are missing a great opportunity to engage a readership which goes beyond your perceived demographic.”

The GDPR requires websites to obtain consent from users before collecting personal information, explain what data are being collected and why, and delete a user’s information if requested. Violating the GDPR can draw a hefty fine — as much as 4 percent of a company’s annual revenue.

Websites had two years to get ready for the GDPR. Rather than comply, about a third of the 100 largest U.S. newspapers have opted to block their sites in Europe. They include the Chicago Tribune, New York Daily News, Dallas Morning News, Newsday and The Virginian-Pilot.

Joseph O’Connor, a self-described “rogue archivist” in the United Kingdom, has been tracking the issue. He started after a gunman killed five staff members of the Capital Gazette on June 28. O’Connor wanted to read about the shooting, but the paper in Annapolis, Maryland, and the nearby Baltimore Sun, both Tronc properties, are blocked in Europe.

As of Monday, O’Connor found that more than 1,000 news sites were unavailable in the EU. They included more than 40 broadcast websites and about 100 sites operated under GateHouse’s Wicked Local brand.

GateHouse and Tronc did not respond to requests for comment about the GDPR. Lee Enterprises has no plans to comply. Company spokesperson Charles Arms said Lee’s websites wouldn’t draw enough visitors from the more than 30 countries in the EU and the European Economic Area to justify compliance.

“Internet traffic on our local news sites originating from the EU and EEA is de minimis, and we believe blocking that traffic is in the best interest of our local media clients,” Arms said.

From a financial standpoint, that position is justified, according to Alan Mutter, who teaches media economics at the University of California at Berkeley. He said international web traffic might benefit The New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Washington Post but “ads served in Paris, Palermo, or Potsdam don’t help advertisers in Peoria.”

But being available in Europe can help customer relations. And about 16 million Americans visited Europe last year.

People in Europe who have encountered a blocked news site can circumvent the problem by using a virtual private network. Maggie Magliato, a recent college graduate from Northern Virginia working as an au pair in Spain, found a workaround when she was unable to access the Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star online: A friend made a PDF of an article and emailed it to her.

But the ultimate solution is to comply with the GDPR, said Craig Vodnik, a Chicago-based business consultant with an office in Europe.

Vodnik was in Cologne, Germany, on July 5 trying to read the news back home. He was shocked to find that the websites of the Chicago Tribune and affiliated WGN-TV were blocked: “Do they really not care about international travelers?”

Sarah Toporoff, a Massachusetts native who works in Paris for the Global Editors Network, which promotes newsroom innovation, raised similar questions. She said U.S. newsrooms “are a benchmark for digital innovation” — and it’s important that their content be available in Europe.

“It is naive and wholly irresponsible to think that U.S. news holds no relevance beyond U.S. borders,” Toporoff said. “U.S. brands should be better at knowledge sharing with their European counterparts and learn how to serve audiences within the GDPR’s parameters. Not to do so is quite undemocratic.”

Jeff South is a journalism professor at Virginia Commonwealth University. He’s spent the summer teaching and doing research in Europe, where he’s had ample opportunity to notice unavailable U.S. news sites.