“Many journalists before me have courted this tale, for good reason. The story of baby Tegan is one of the greatest mysteries of our times. Keli, the most important person of all, has never spoken.”

Most Americans have never heard of Keli Lane or of her baby, Tegan, who disappeared in 1996 when she was only two days old. But the case of Lane — and her murder conviction in 2011, though no body or hard evidence was ever found — has gripped Australia for years. It’s now the subject of a three-part Australian Broadcasting Corporation documentary — and a Facebook group that, in around two weeks, has grown to 29,000 members focused on one goal: finding out what actually happened to Tegan. Lane, who is in prison with a chance of parole in 2023, insists that she handed over the baby to her biological father in the hospital’s lobby after her birth, and believes that she’s still alive.

The ABC’s documentary itself is ridiculously gripping — this whole article would make more sense if you could watch it, but Americans can’t due to territorial restrictions; I watched a press copy on Vimeo and hope it’s more widely available soon — and digs up layer upon layer not just of new evidence but of engrained sexism and misogyny. It feels comparable to the first season of Serial, and it’s not surprising that people have poured into ABC’s Facebook group to try to continue the investigation, which remains unresolved at the end of the third and final episode. (As in the case of Adnan Syed, calls to reopen Lane’s case are growing.) Here’s a segment from Studio 10 that gives you detail (though also some spoilers, if you plan on watching the whole series):

“We realized we probably still have a bit of the way to go here,” said Caro Meldrum-Hanna, 37, an investigative reporter. (Meldrum-Hanna is a fairly gripping character herself, both as a major figure in the documentary — along with her colleague Elise Worthington — and as an award-winning journalist.) “We’d been calling out to the audience on screen through the conventional television series, asking, ‘Do you know more? Were you there that day?’ We were constantly putting up our email address and engaging the audience. Leads were coming in, but then all of a sudden, the inbox was really deep. We were like, hooly dooly! We’re not going to be able to manage all of this between the episodes.

“It’s a watercooler sort of program. Everyone was talking about it. I’d be on the bus, the ferry to work, I’m being stopped in the street to talk about Keli Lane. I’m not a big star, but it’s something that people are obsessed with — the mystery of where the baby is. The Facebook group was Flip [Prior, who works in content research, strategy, and news innovation at the ABC]’s fantastic idea: How do we harness this window at the moment where we’ve captured people’s attention? Do we just let that fall away and leave people wondering, or do we find a space and a way to get people engaging and communicating with each other?

“I hadn’t done this before. I just go down a hole as an investigative journalist, pop out the other side, and say, ‘Here, Australians, here’s what we’ve got.’ I’ve never been this engaged with the audience.”

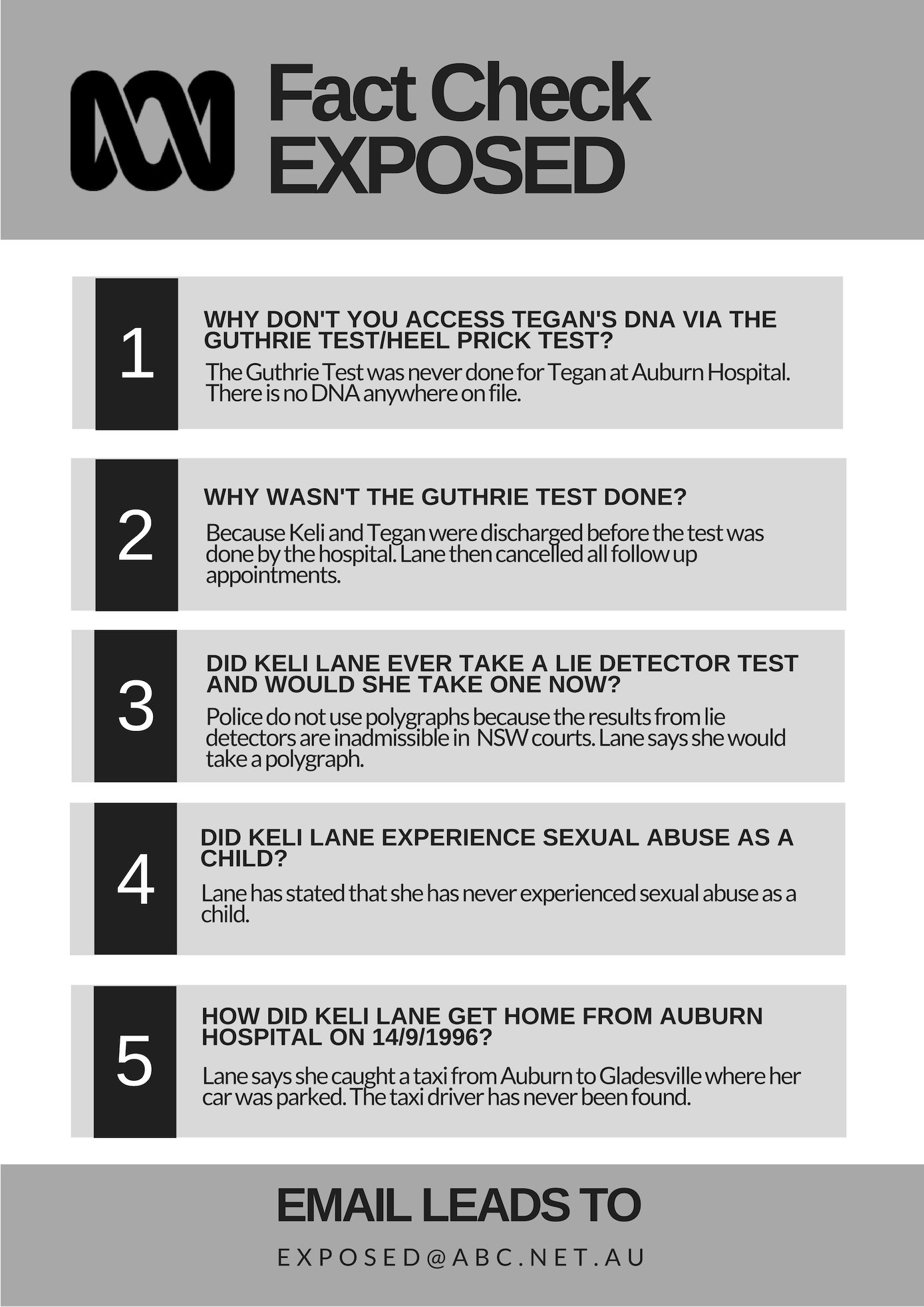

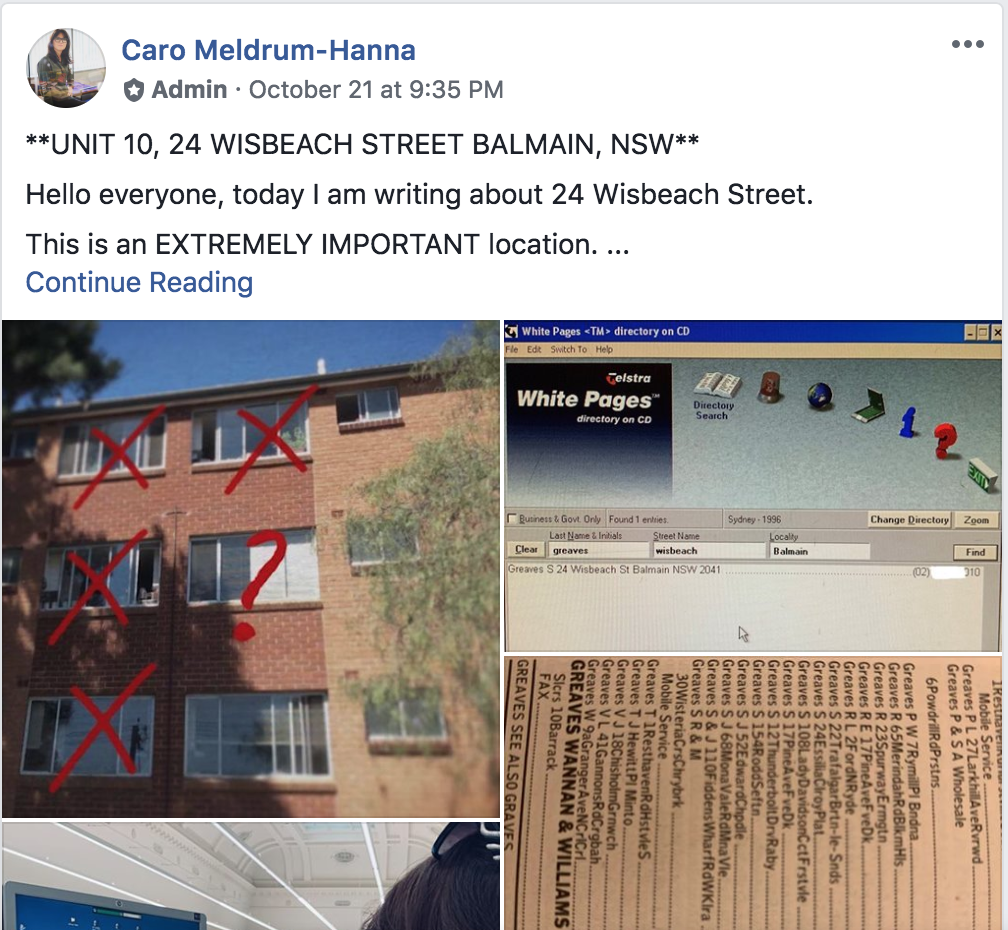

The Facebook group, launched in tandem with the third and final episode on October 9, hit 12,000 members overnight and, a little over two weeks later, is over 30,000. Meldrum-Hanna posts daily updates and provides members with specific tasks to help the team with the case. She also posts debunks to dispel and challenge some of the biggest myths that have cropped up around the story. Reporters Jennine Khalik and Dunja Karagic have been moderating the group and documenting new tips and leads.

The Facebook group, launched in tandem with the third and final episode on October 9, hit 12,000 members overnight and, a little over two weeks later, is over 30,000. Meldrum-Hanna posts daily updates and provides members with specific tasks to help the team with the case. She also posts debunks to dispel and challenge some of the biggest myths that have cropped up around the story. Reporters Jennine Khalik and Dunja Karagic have been moderating the group and documenting new tips and leads.

“It’s an incredibly actively engaged group of people,” said Prior. “It’s about 85 percent women; the vast majority are active Facebook group members, and they are in the exact demographic we’re trying to reach, 25–54.”

It’s easy to see how a massive Facebook group of amateur sleuths trying to solve a murder could go completely off the rails, and the only reason this one hasn’t is extremely careful management by ABC in terms of moderating, harnessing the help of about 20 group members (including several ex-journalists) as “superusers” to keep conversations on track, and promptly shutting down past threads in order to keep people focused on current challenges. The group initially allowed open posting, which led — not surprisingly — to a wave of conspiracy theories and ranting in its first couple of days. Now comments are limited to just one post at a time.

The administrators also have to be on the lookout for legally contentious subjects — people’s names, for instance — and manually remove posts containing them. “We have to do Crowdtangle keyword searches and alerts, which is difficult because Crowdtangle only searches posts, not comments,” Prior said. “Facebook’s tools are not amazing. You can’t do things like automatically hide certain keywords. We have made a few comments to Facebook since we started this, saying ‘you really need to improve your tools if you want people to be using groups.'”

On the day we talked, for instance, the group was focused on Auburn Hospital, where Lane gave birth to the baby. “As is the way with the tyranny of time, the old hospital no longer exists. The building’s been demolished,” Meldrum-Hanna said. “We could never go back there and canvass the place. We put a call out and said, look, we couldn’t access the plans to the hospital and couldn’t find any more photos — did anyone work there? And it was so wonderful: We had people, it must have been librarians or archivists, pulling out old floor plans of the hospital. Yesterday we managed to get a CD-ROM of the floor plans of the hospital from the 1970s that showed the layout, where the emergency stairwells were, where the rubbish disposal area was, where the incinerator was — because there was a theory she may have exited through the back passage and killed the baby on site, and now that was another theory we could debunk. We couldn’t get the plans but through the audience we managed to do it. I feel like screaming, hurray, how awesome.”

“People really do appreciate the direct contact with the journalists,” Prior said. “Some people just want to come and do the virtual watercooler, but others want to get actively engaged in helping the case. I’ve been quite amazed that some of the people who have popped up to offer their help have been legal experts, former journalists, former policemen, all coming through this group and saying hey, look, I want to work on this and I have some people who can help. We’re overwhelmed with offers, because of this.”