The growing stream of reporting on and data about fake news, misinformation, partisan content, and news literacy is hard to keep up with. This weekly roundup offers the highlights of what you might have missed.

If you ever see an article on n13m4nl4b.org, it’s fake. The Citizen Lab at University of Toronto released a case study of Endless Mayfly, “an Iran-aligned network of inauthentic websites and online personas used to spread false and divisive information primarily targeting Saudi Arabia, the United States, and Israel.” Here’s how the “disinformation supply chain” worked:

Step 1: Create personas: Endless Mayfly personas establish social media identities that are used to amplify specific narratives and propagate Endless Mayfly content.

Step 2: Impersonate established media sites: Using typosquatting and scraped content, sites are created to impersonate established media outlets, such as Haaretz and The Guardian, which then serve as platforms for the inauthentic articles.

Step 3: Create inauthentic content: Stories combining false claims and factual content are published on the copycat sites or as user-generated content on third-party sites.

Step 4: Amplify inauthentic content: Endless Mayfly personas amplify the content by deploying a range of techniques from tweeting the inauthentic articles to privately messaging journalists. Multiple Iran-aligned websites also propagate content in some instances. In one case, bot activity was observed on Twitter.

Step 5: Deletion and redirection: After achieving a degree of amplification, Endless Mayfly operators deleted the inauthentic articles and redirected the links to the legitimate news sites that they had impersonated. References to the false content would continue to exist online, however, further creating the appearance of a legitimate story, while obscuring its origins.

One of the fake articles created was purportedly by The Atlantic. Alexis Madrigal runs down how you’d spot that the articles were fake. It wasn’t too hard to tell if you’re a savvy news reader — though that doesn’t mean that some legitimate media outlets weren’t fooled. For instance:

The lede also doesn’t spell out F(oreign) M(inister), which American news organizations would. The sentence is grammatically flawed. The rest of the article displays a similar lack of familiarity with journalistic conventions. As good as the design knockoff was, the text was a terribly amateurish counterfeit.

And the tweet distribution was equally bad. As far as Citizen Lab could tell, all 2,700 of the tweets to the fake story may have yielded only a few thousand clicks. Does that influence much? Even multiplied across more than a dozen similar efforts with other publications like The Guardian and The Globe and Mail?

Directly, it seems highly unlikely. But on three occasions, legitimate news organizations — Reuters, Le Soir, and Haaretz — picked up a fake story and ran with it. In the Reuters case, this led to a burst of attention from other sites before a retraction was published.

Among other things, no one here would get away with a lede this bad https://t.co/vKdEwrBXBE pic.twitter.com/T00ClzSx1s

— McKay Coppins (@mckaycoppins) May 15, 2019

“Seemingly trivial decisions…” This study isn’t directly related to misinformation, but it’s interesting as a reminder that the way researchers ask a question affects the answer: A study from the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg Public Policy Center found that “seemingly trivial decisions made when constructing questions can, in some cases, significantly alter the proportion of the American public who appear to believe in human-caused climate change.”

Surveying more than 7,000 people, the researchers found that the proportion of Americans who believe that climate change is human-caused ranges from 50 percent to 71 percent, depending on the question format. And the number of self-identified Republicans who say they accept climate change as human-caused varied even more dramatically, from 29 percent to 61 percent.

“People’s beliefs about climate change play an important role in how they think about solutions to it,” said the lead author, Matthew Motta, one of four APPC postdoctoral fellows who conducted the study. “If we can’t accurately measure those beliefs, we may be under- or overestimating their support for different solutions. If we want to understand why the public supports or opposes different policy solutions to climate change, we need to understand what their views are on the science.”

Participants were asked the question in three different ways:

Given the option to respond with a choice of “don’t know” or allowed to just skip the question (a “hard” don’t know vs. a “soft” don’t know) [This is the “Pew-style” approach];

— Provided with explanatory text saying that climate change is caused by greenhouse gas emissions, or given no additional text apart from the question;

— Presented with discrete, multiple-choice responses and asked to pick the one that comes closest to their views — or shown a statement and asked how strongly they agreed or disagreed with it, using a seven-point agree-disagree scale

The first and third options produced strikingly different results:

The “Pew Style” approach, which uses a clear “don’t know” option, no explanatory text, and a discrete choice among statements as to which best represents your views, produced the lowest acceptance of human-caused climate change: 50 percent of U.S. adults and just 29 percent of Republicans.

The van Boven et al. approach cited by Leaf van Boven and David Sherman in a 2018 New York Times op-ed, “Actually, Republicans Do Believe in Climate Change.” This approach uses an agree-disagree scale and explanatory text and does not offer a “don’t know” option. In the present study, this format combination found that 71 percent of U.S. adults believe in human-caused climate change and 61 percent of Republicans — the highest level of acceptance among the eight question formats studied.

In their paper, the researchers write:

We want to be clear that this research cannot (and does not) offer a single measurement strategy as a “gold standard.” Although we show that some design decisions produce higher estimates of belief in [human-caused climate change] than others, it is not possible to conclude from this research that any one measurement format is somehow “better” than the others. Instead, we think that our work should be considered an important first step in determining how to best measure climate change belief in the mass public.

“Whatever WhatsApp does, there’s a workaround.” WhatsApp has tried to fight the spread of fake news by adding app controls that limit the number of times a message can be forwarded to five. But this week Reuters reported how easy it is to get around those controls: “WhatsApp clones and software tools that cost as little as $14 are helping Indian digital marketers and political activists bypass anti-spam restrictions set up by the world’s most popular messaging app.”The published version of this piece adds additional analyses showing that Democrats and Republicans _alike_ are influenced by these seemingly minor changes; and to very similar degrees. pic.twitter.com/sGl4W6vcd3

— Matt Motta (@matt_motta) May 2, 2019

Bad news: It does not seem hard to beat the five-forwards limit on WhatsApp, which was the company’s primary defense against mass disinformation. https://t.co/MdJOj6a5Gv

— Joseph Menn (@josephmenn) May 16, 2019

Reuters found WhatsApp was misused in at least three ways in India for political campaigning: free clone apps available online were used by some BJP and Congress workers to manually forward messages on a mass basis; software tools which allow users to automate delivery of WhatsApp messages; and some firms offering political workers the chance to go onto a website and send bulk WhatsApp messages from anonymous numbers.

It’s not just India: “Tools purporting to bypass WhatsApp restrictions are advertised in videos and online forums aimed at users in Indonesia and Nigeria, both of which held major elections this year.”

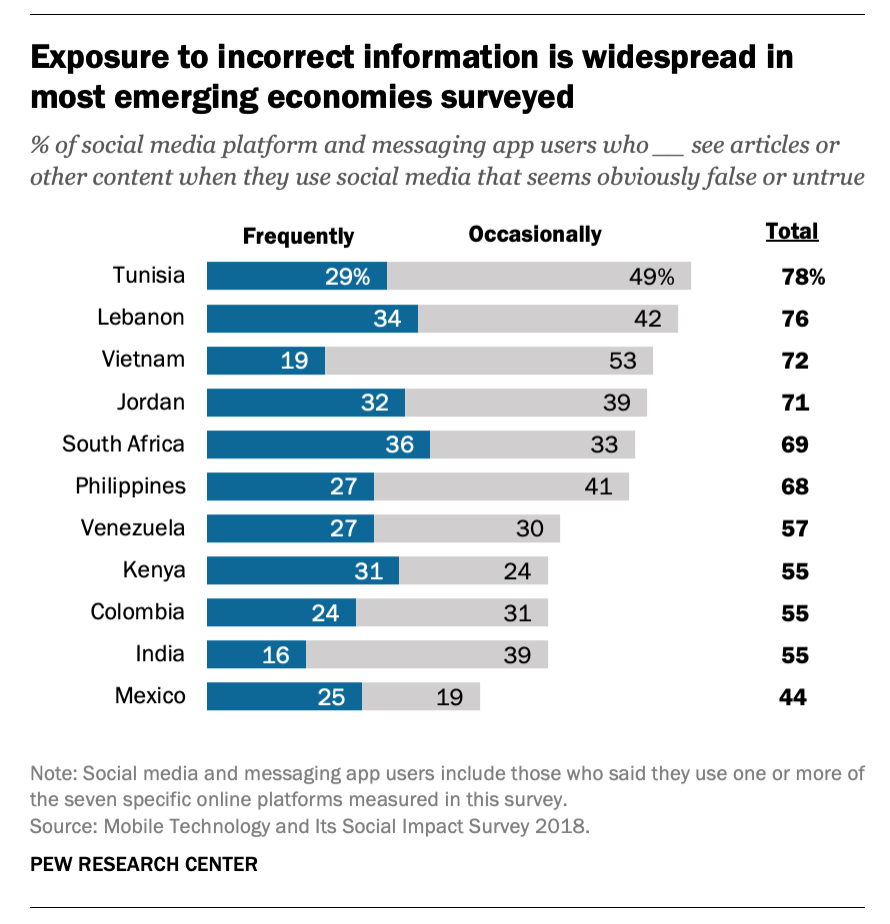

“The phrase ‘fake news’ was sometimes mentioned in English.” Pew surveyed citizens in 11 emerging markets (Tunisia, Lebanon, Vietnam, Jordan, South Africa, the Philippines, Venezuela, Colombia, India, and Mexico) about the misinformation that they see and how worried they are about it.

A median of 64% of adults across the countries surveyed say people should be very concerned about exposure to false or incorrect information when using their mobile phones. In India, a country where journalists and politicians have focused on the dangers of misinformation for their election, this concern is second only to the worry that children will be exposed to immoral information.

Focus groups conducted by the Center in advance of the survey highlighted people’s different experiences with false or incorrect information. Even though the bulk of the sessions were conducted in other languages, the phrase “fake news” was sometimes mentioned in English. Some participants mentioned challenges in knowing the source of the posts they saw on social media, difficulties verifying the things they encountered there or having to triangulate among multiple sources to determine what was true and what was not. Others worried about posts seeking to actively mislead people or stoke animosity between political parties (in the Philippines and Mexico) or tribes (in Kenya).