Welcome to Hot Pod, a newsletter about podcasts. This is issue 248, dated March 3, 2020.

This came in yesterday: Pocket Casts, the popular third-party podcast app, is receiving new investment money from BBC Studios, a commercial arm of the BBC. In addition to getting more funds to expand and carry out its operations, the investment also means that BBC Studios joins the coalition of public media companies that has collectively owned Pocket Casts since May 2018, which includes NPR, WNYC, WBEZ, and This American Life.My sense is that the underlying thinking behind Pocket Casts has remained the same since that acquisition. You can read all about that here.

All the news that’s fit to Mailkimp. Who are we if we are not fretting about The New York Times?

Ben Smith, the former editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News, began his tenure as the David Carr-descended media columnist over at the Gray Lady this past Sunday, and his inaugural missive is…well, about the Times. Specifically, it’s about how the Times’ increasing success as a singular journalistic institution may well be a detriment to the news business as a whole, particularly within the context of an increasingly consolidated environment in which everybody’s doing everything — a newspaper is also a podcaster, a blog is also a Hollywood IP machine, Vaulter is connected to a cruise line — and where a likely end result is an insurmountable gulf between a single diversifying player and everybody else — which is great for the Times but not so great for the news business.

(This environment also puts media columnists in a weird situation, since everything they write about could complicate the various activities of their employers. Then again, maybe that’s the point.)

In other words, the column advances a take that the dude Josh Benton has been slinging for a bit now. But it comes with some fresh news that’s explicitly relevant to us here in podcast-land.First, Smith confirms Ben Mullin’s report over at The Wall Street Journal that Serial Productions has been exploring a sale. Then he specifies that the Times is in “exclusive talks” to acquire the This American Life spinoff podcast studio. He also gives a number: Serial Productions — which houses Serial and S-Town, along with various projects in development that aren’t This American Life — was valued at $75 million, though if a deal actually gets done, the Times is expected to pay less than that.

That $75 million number is definitely curious, given that we’re talking about one of the most valuable podcast studios on the market, which owns what is perhaps the most lauded podcast of all time. That number would also place the deal vaguely in Parcast territory, which was $56 million guaranteed plus $47 million in incentives. But I wouldn’t go too far with that comparison; The New York Times is fundamentally a different kind of buyer than Spotify, which is in a position to be significantly more aggressive with its deals, and an acquisition of Serial Productions would probably require more work around the preservation of culture, identity, and brand power.

Second, the column also highlights what would be the strategic pathway for the Times deal: “The deal, along with The Daily, the popular weekday podcast at The Times, could form the basis for an ambitious new paid product — like the company’s Cooking and Crossword apps — that executives believe could become the HBO of podcasts.” In other words, we could very well be talking about an actual spinout paid podcast app built around the Times’ audio assets.

Yes, the fact that yet another party had invoked the classic “HBO of podcasts” construct triggered groans in some podcast corners, but I dunno — I kinda feel it would actually be pretty apt in this context. After all, we’re talking about a tightly curated portfolio of premium — in the genuine sense of the word! — podcasts that are monetized as a bundle within a broader, validated business model.

Of course, this very idea raises the possibility of a universe where The Daily could be dragged behind a paywall, if doesn’t end up being deployed as a top-of-the-funnel draw. But whatever the scenario, this theoretical NYT Audio app would in large part be marketed towards a demographic that’s already inclined to pay for more NYT stuff. Consider the system-level upside of what happens next: This could help get more people used to paying for podcasts. More so than Luminary, anyway.

I’d stroke my chin, but we’re not supposed to be touching our faces right now. Oh, speaking of…

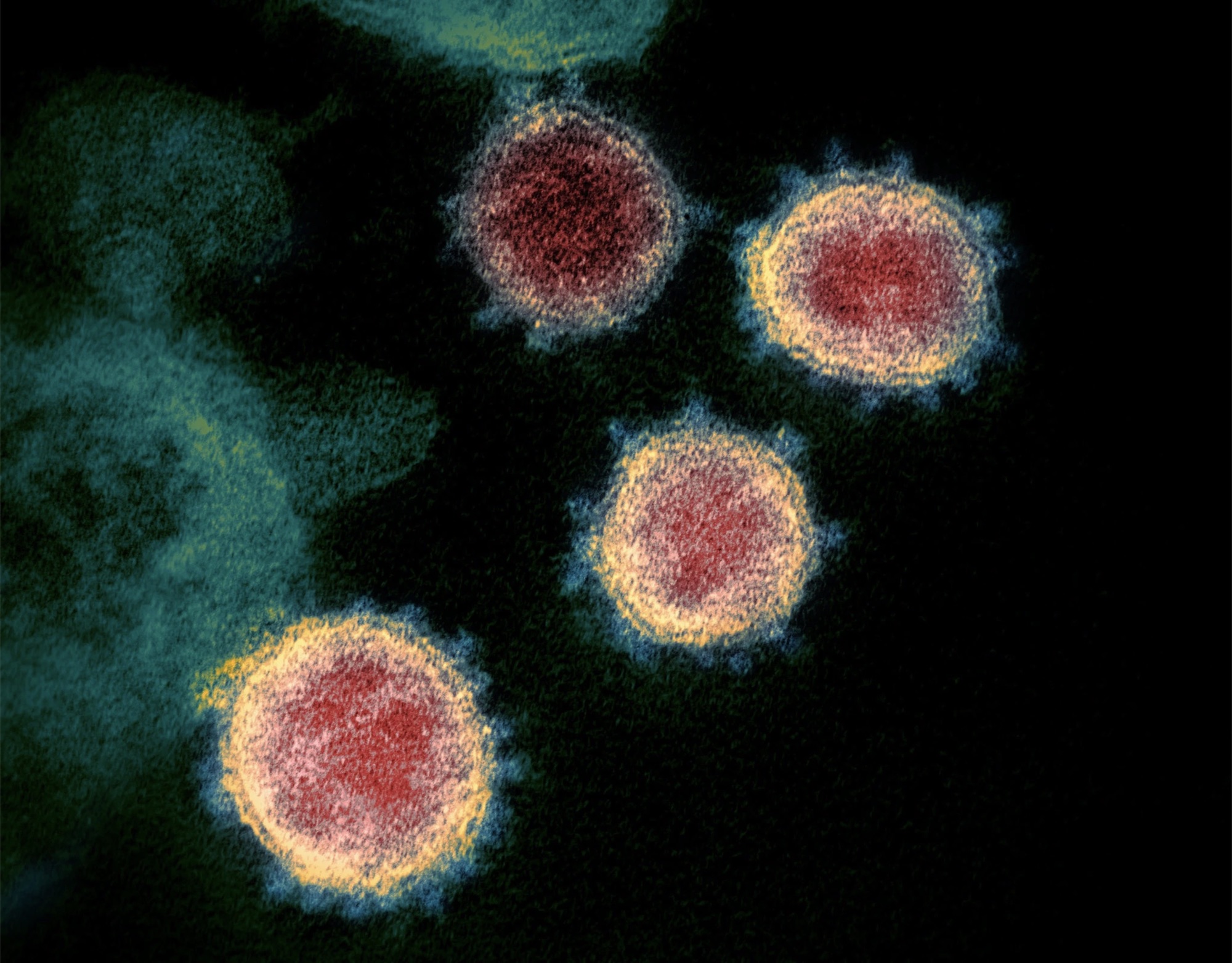

Outbreak. Much like the wave of impeachment pods that spread across the United States a few months ago, a wave of coronavirus pods feels imminent. Over the past few days, CNN and ThreeUncannyFour have both launched new audio projects that will cover the outbreak, and they almost certainly will not be the last.

The radio listserv in 2020 [by Caroline Crampton]. If you’re involved in audio production in a professional or semi-professional way, you’re probably a member of at least one email listserv about it. There are lists based on geographic location — of which NYC Radio is probably the best known to a U.S. audience — as well as those devoted to other kinds of community or identity, such as Ladio, Gaydio, and Producers for Diversity in Public Media. Like lots of readers, I use lists like these everyday, but it’s only recently that I started thinking about why they’re so important to this industry and how they can adapt to the changing demands of work in 2020.

For the purposes of this piece, I’m using the term “listserv” generically to refer to the category of software that allows messages to be distributed transparently to a list of email addresses just by sending a single email, rather than meaning the specific trademarked application of the name. Listservs are old-fashioned internet technology, first used widely in the 1980s and updated through a variety of iterations over the decades. These days, the easiest way to create and maintain one is through something like Google Groups, although plenty of more old-school options still exist as well.

Given that so many other ways to connect and form communities now exist — from Facebook Groups to Slack to Twitter and so on — why do listservs remain so vital? There are great projects being run outside of them too, don’t get me wrong — the PoC in Audio database is one that springs to mind. But plenty of instant messaging tools have promised to minimize or even eliminate email from our workflow, and yet this simple email-based system is still thriving, with busier audio-related listservs seeing dozens of posts a day.

On a fundamental level, I think listservs have stuck around precisely because email is so ubiquitous. It’s an extremely rare person these days who doesn’t have an email account they use regularly, so an email-based community is a pretty accessible one. There’s no need to download a new app or learn the rules and etiquette of a new platform. Any of those other examples would automatically exclude people who don’t use Facebook, say, or aren’t interested in adopting Slack, whereas email is a universal presence.

In some ways, the lo-fi nature of a listserv is a distinct advantage in the modern age. Unless moderators so choose, there doesn’t need to be an obvious front-end presence for the list, meaning that new members are mostly introduced by word of mouth and therefore tend to be genuinely interested in participating in the community. It doesn’t require huge amounts of attention from members to exist either — no constant notifications or updates needed. From a technological standpoint too, it’s pretty low maintenance, with little time-consuming upkeep required from a webmaster or moderator.

However, for a listserv to be more than just a distribution list used to publicize job requests, there’s more work involved. Plenty of the examples I’ve already mentioned work really well for this purpose, with companies and production houses using them to source stringers and producers in other locations for freelance work. But I’ve also used the word “community” a few times in relation to this kind of organizing, and in some cases that’s what a listserv becomes, with regular conversation on much broader topics that over time nurture a sense of belonging, and can even foster change in the wider industry.

With this in mind, I caught up late last week with Lily Ames, who founded the UK Audio Network listserv. She started it in August 2017, inspired by various U.S.-based groups and wanting to provide the infrastructure for greater transparency for those working in audio in the U.K. More than two years on, Ames is now running a survey about the future of this group with the intention of building on the basic foundation to enhance the community’s offering.

As a forum for job callouts, UKAN is working well, she said. But there’s more it could be doing: “I think I would like people to give just as much as they take. That’s what needs more work from me to make happen.”

She elaborated: “Taking is just posting tape syncs when you need them without posting real jobs or bigger contracts for your show. Taking is just posting tape syncs without taking the time to get to know that producer who you’ve hired for the day — they could be, you know, a really interesting candidate who just is freelancing right now. When you’re in a higher up position — if you run a company, you’re a commissioner, you’re a senior producer — and you’re adding junior people to the list, you have to make sure that you’re actually then in turn posting opportunities to the list.”

At the moment, “I can see that it’s skewing more towards taking,” Ames said. But it takes work to encourage other kinds of activity, which Ames herself doesn’t always have time to do (she’s the head of production at Chalk and Blade, a London-based shop making shows for the BBC, Pushkin, Audible, and others). “You have to kind of cultivate a sense that this is a thriving, exciting community, and that’s done through work like reiterating the values, through reinforcing rules through outreach, through innovation where possible.”

UKAN has already done some valuable work to help even out the uneven power dynamics in the U.K. audio scene — we reported on a pay survey facilitated via the list back in May 2019, for instance, and there have been some useful conversations about diversity (or the lack of it) when it comes to awards lineups. Alongside the email list, UKAN has a resources section with studio and gear hire databases, legal factsheets, production templates and other helpful documents.

However, Ames has observed what she thinks is some cultural differences that sometimes prevent the U.K. list from being as transparent or direct as its U.S. counterparts (she herself is a Canadian who moved to the U.K. in 2014). “It kind of evolved very differently, I think mainly because of the difference between British culture and American culture. People kind of look to me to run it as opposed to it being self-run,” she said.

And sometimes there’s a reticence to post publicly that can be frustrating. “A post goes up and it’s controversial in some way — those posts are kind of important because they can start a conversation. They can alert everyone to what the problem is and why it’s a problem. On the American ones, people jump in right away say, ‘This is problematic and this is why it’s problematic.’ And I was expecting that to happen for the British one, but people just send me a very thoughtful individual email when I was expecting a reply-all to the whole group.”

That’s why the survey can help steer the group’s future — armed with information about what the 1,400 and counting members want from UKAN, Ames says she can make plans to improve things. In an audio scene that to date has been very dominated by the BBC and its big providers, it’s valuable to have an open conversation in a place everyone can access, like their email inbox. “I think it’s really important when you’re disrupting power dynamics that everyone is involved in the conversation. The higher-ups are reading,” Ames said. “They’re watching those posts. They’re watching closely.”

UKAN is a relatively young listserv, and the unique aspects of the U.K. audio scene probably make it inadvisable to read across too much to other communities in other places. But as a case study for what a listserv can offer in 2020, it’s a fascinating example of how an old-fashioned technology is still facilitating innovation. At a moment when there’s a movement in some quarters towards greater unionization, listservs can provide some of that solidarity and collectiveness to those who don’t have other options to organize.

PRX changes. The public media organisation PRX has added four new members to its board of directors: Jene Elzie of Athletes First Partners, Rima Hyder of FactSet, Tanya Jones of Aya Global, and Claudia Palmer of WGBH in Boston. In addition, Jon Abbott, the president and CEO of WGBH, has completed his eight-year term on the board. Ma’ayan Plaut, formerly the podcast librarian at RadioPublic, has also joined the PRX marketing team to work on audience development.

This week in politics, and all the weeks after that. It’s Super Tuesday, folks, one of the more consequential dates on the American presidential elections calendar, so it’s only fitting that we do a couple things on politics and podcasts.

First things first. Ahead of today’s big occasion, I wrote a lengthy essay for Vulture last week on the ever-healthy election podcast subgenre, revisiting its boom during the 2016 cycle and exploring how the subgenre has evolved since then.

It’s mostly a recent history piece, one where I tried to argue the ways in which the 2016 election cycle helped pushed podcasting towards innovation and industrialization in specific ways. But it was also an opportunity to mull over something I’ve long wondered about: As we move deeper into the 2020 cycle, can we say unambiguously that politics podcasts, far from being tech oddities, are properly part of the wider media ecosystem with the capacity to really affect society, political opinion, and electoral outcomes?

However you approach that question, I think we can at least acknowledge that the relationship between politics and podcasting has grown noticeably more complicated since 2016. Consider Joe Rogan’s endorsement of Bernie Sanders, and how that was treated with seriousness. Same goes for the ongoing phenomenon of Chapo Trap House, the prime church of the “Dirtbag Left.”

Speaking of, Chapo Trap House was the subject of a Nellie Bowles portrait in The New York Times that caused a stir over the weekend. It’s the sort of writeup that tends to draw strong (typically negative) reactions from all sides, whether it’s Chapo followers displeased about the way they’re portrayed or folks wary about those followers and what they suggest about certain corners of the Sanders movement. For what it’s worth, I thought the piece did its job, functioning better as an illustration of a phenomenon than an analysis of it, though it does risk positioning the podcast and its followers as overly representative (synecdochal?) of the Sanders base. And what a wild picture it paints of Chapo Trap House: frustrating, peppered with internal contradictions, and a little scary, but also resonant, voracious in its beliefs, and compelling in its anger.

Meanwhile, 2016 continues to not end. On Thursday, Politico reported that Hillary Clinton is apparently planning to launch a podcast with iHeartMedia. I should note that the writeup doesn’t mention that this won’t be the first time Clinton is hitting the podcast well: that honor goes to With Her, the agitprop-ish official campaign podcast that was produced by Pineapple Street (now an Entercom company).

But there’s nonetheless some meat on this bone. Much is made in the Politico piece about one of the key inspirations for the new Clinton pod: Howard Stern, the legendary radio talent whose on-mic ability, persona, and multiyear exclusive contract basically laid the foundation for SiriusXM. Also interesting are the people who will apparently be producing the show: Kathleen Russo, credited as the creator of WNYC’s Here’s The Thing with Alec Baldwin, and Julie Subrin, the former executive producer of audio at Tablet.

Not that anybody’s asking, but I find the choice to partner with iHeartMedia somewhat unexpected, given the existence of Crooked Media, the wildly popular progressive media company founded by a crew of former Obama staffers — which is now expanding beyond politics, by the way — and Higher Ground, the Obamas’ production company that has a podcast partnership with Spotify, which is decidedly sexier. Then again, maybe a close association with the Obama administration isn’t something the Clinton camp finds agreeable, and perhaps working with an old-school radio giant that’s working hard to drag itself out of a bankruptcy and reposition itself as a next-generation audio company is more…appropriate.

Anyway, Clinton’s reentry into the podcast world raises another question: What’s the over/under on the amount of time before we get a Buttigieg/Klobuchar pod? A Yang pod, meanwhile, feels imminent.