America’s high school students are mostly sitting at home right now, alternating between scrolling Instagram, being bored, and being bored while scrolling Instagram. The New York Times wants to give them something to do.

Through a deal with Verizon, the Times is giving free access to NYTimes.com and its mobile apps to American high school students for the next three months. The idea is that Times journalism can keep students informed as they deal with the dislocation caused by the coronavirus and the social constraints imposed on Americans as a result.

“From April 6 to July 6, students and teachers will be able to access Times journalism online,” said Times CEO Mark Thompson and Verizon CEO Hans Vestberg in a joint release. “This means that even while studying remotely, students will have deeply reported, expert journalism at their fingertips — from international issues to arts and culture to science, politics and more.”

It’s a good deal for the kids, obviously, and it’s a good deal for the Times, for reasons discussed below. It’s also the latest event in more than two centuries of intersection between America’s newspapers and its schools — an exchange that’s mixed civic and commercial interests in ways that try to advance both.

On June 8, 1795, the Portland Eastern Herald of Maine published an editorial proclaiming the merits of newspapers as a teaching tool.

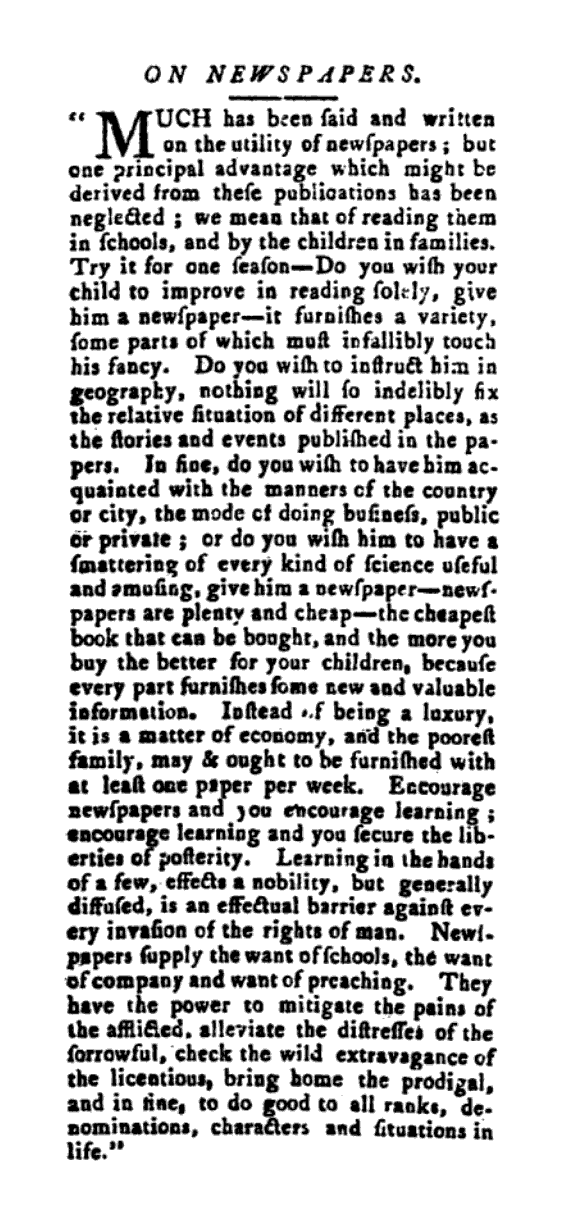

“Much has been said and written on the utility of newspapers,” it argued, “but one principal advantage which might be derived from these publications has been neglected; we mean that of reading them in schools, and by the children in families…Learning in the hands of a few effects a nobility, but generally diffused is an effective barrier against the every invasion of the rights of man.”

That combination — of honest hopes for improved social welfare and financial self-interest — has marked the relationship between newspapers and education across the two-plus centuries since. Newspapers-in-education programs took off in the United States in the 1930s and have both given students a window into the broader world and inculcated the newspaper-reading habit in generations of young future subscribers.

No American newspaper has leaned into that project more than The New York Times, which has used its perch as a national newspaper to dip repeatedly into the education world. Just to look at the past couple of decades: Its Knowledge Network was an early attempt to link “Times content with faculty course material for both credit-bearing and continuing education courses” online, in 2007. In 2008, it bought a majority share of Epsilen, an online-learning platform. By 2010, it first partnered with universities to jointly offer for-credit courses, like a video class at Ball State’s j-school, and running a statewide initiative in Texas public schools. In 2011, it started offering teacher certification courses with an Arizona community college and continuing ed classes with USC.

Those efforts developed at a time when the Times was seeking to diversify company revenue. But the cash crunch of the financial crisis led the paper to sell off its non-core assets and retrench around its central product, with many of those education partnerships falling away. (It sold Epsilen in 2012.) But they never stopped.

(Did you know you can attend summer school at The School of The New York Times for just $5,825? Pay $95 to learn how to be a critic from A.O. Scott and Ben Brantley? Earn a certificate in virtual reality?)

The decision to focus on its news product has paid off, of course, with a boom in digital subscriptions, a growing newsroom, and a generally robust future ahead of it. And some of its most noteworthy engagements with education have come with that core news offering.

In early 2017, after Donald Trump’s election, there was a swell of audience interest in and goodwill toward high-level journalism, illustrated most clearly by the “Trump bump” in subscriptions the Times and others experienced. To try to capture a bit more of that spike, the Times launched a simple program that let anyone “sponsor” a Times digital subscription for a high school student. “Sponsor a student subscription and inspire the future generation of readers,” it pitched.

Given that the marginal cost of an additional Times digital subscription is essentially zero, this functioned essentially as a donation to the Times — which, as a for-profit company and a proud institution, would find it difficult to just put a “Donate” button on article pages. Within one month, 15,500 donors had “sponsored” 1.3 million student subscriptions. (Some back-of-the-envelope math suggests that generated about $2 million for the Times.)

Since then, the Times has gone back to the idea of sponsoring subscriptions for revenue. Last fall, it announced a partnership with Verizon to give free NYTimes.com access to students in Title I high schools (those with higher populations of poor and disadvantaged students). Of note in that announcement: Students and teachers only had access “when connected to their school’s network” — a situation very few American students are in right now thanks to COVID-19.

Then there’s today’s announcement:

The New York Times Company and Verizon today joined forces to offer all students and teachers in high schools within the U.S. free digital access to NYTimes.com. With students across the country impacted by school closures due to the coronavirus pandemic, this partnership will help to keep them educated, informed and connected.

This time, crucially, access will not require being connected to a school’s network.

Getting in will require teachers or school administrators registering and then giving over a list of their students’ emails. (So if you’ve got a bored high-schooler at home, you may need to bug someone in the school office to get this process going. Or, well, someone who is normally in the school office but currently in their living room.) Sorry, no homeschoolers.

I’m going to assume that Verizon is paying the Times for the privilege here. (No details in the announcement, of course, but the Times could just as easily do this on its own.) But this would still be a very good deal for the Times even if money wasn’t involved and the PR benefit was nil.

Most fundamentally, the Times gets millions of teenagers exposed to Times content — at a moment when, thanks to coronavirus, news consumption is waaaay up for all Americans. It’s easy to imagine these kids thinking of the Times as the place to go when they want to see the latest on the crisis — and some of them sharing Times stories in their networks.

(It’s worth noting, of course, that the closure of schools means that any access to digital content is a matter of what resources students have at home — both in terms of access to a computer or smartphone and in terms of wifi or data access. Those can be wildly unequal from home to home, as America is finding out in its current experiment with distance learning.)

Presumably, the students will get some version of the standard onboarding for new Times subscribers, which pushes newsletters and podcasts like The Daily. Those embed the Times into a daily ritual, either in their inboxes or their podcast app. And if a student subscribes to any, those will keep coming after the three-month free access is over.

The Times also gets all those kids’ email addresses — admittedly, probably their school addresses instead of their Gmails — which (a) makes them registered, logged-in users, making it possible to learn their preferences and what kind of content they like, and (b) opens the door to future email marketing. (If I were the Times, I’d send every kid in this program an email in a couple months offering $1 or some other cheap price to extend access through the November election — another big potential hook to draw in even kids with limited interest in the news.)

And all of this comes with no real financial downside. Not many teenagers have their own paid New York Times subscriptions, so there’s almost no risk of cannibalizing existing customers. The cost of providing access is just processing the email addresses and figuring out a marketing/onboarding plan.

I am of the belief that the Times (and a few other national outlets, plus a larger number of niche outlets) still has a lot of potential growth in the education business. (The fact that coronavirus is currently accelerating distance learning and online education like nothing before will only increase that opportunity. As Scott Galloway recently pointed out, Google searches for “MasterClass” have passed searches for “business school.”) I’m on the record backing an education-ish acquisition like The Great Courses or MasterClass, as both a standalone product line and an upsell to a premium Times subscription.

Education is a hard nut to crack; ask all the people saying MOOCs would take over higher ed a decade ago. But this sort of deal to bring in young readers is a no-brainer.

Just for fun, here’s that piece from the June 8, 1795 Portland Eastern Herald — which survives today in the Portland Press Herald — advocating for the use of newspapers in education.