[Warning: Violent and gruesome metaphor ahead.]

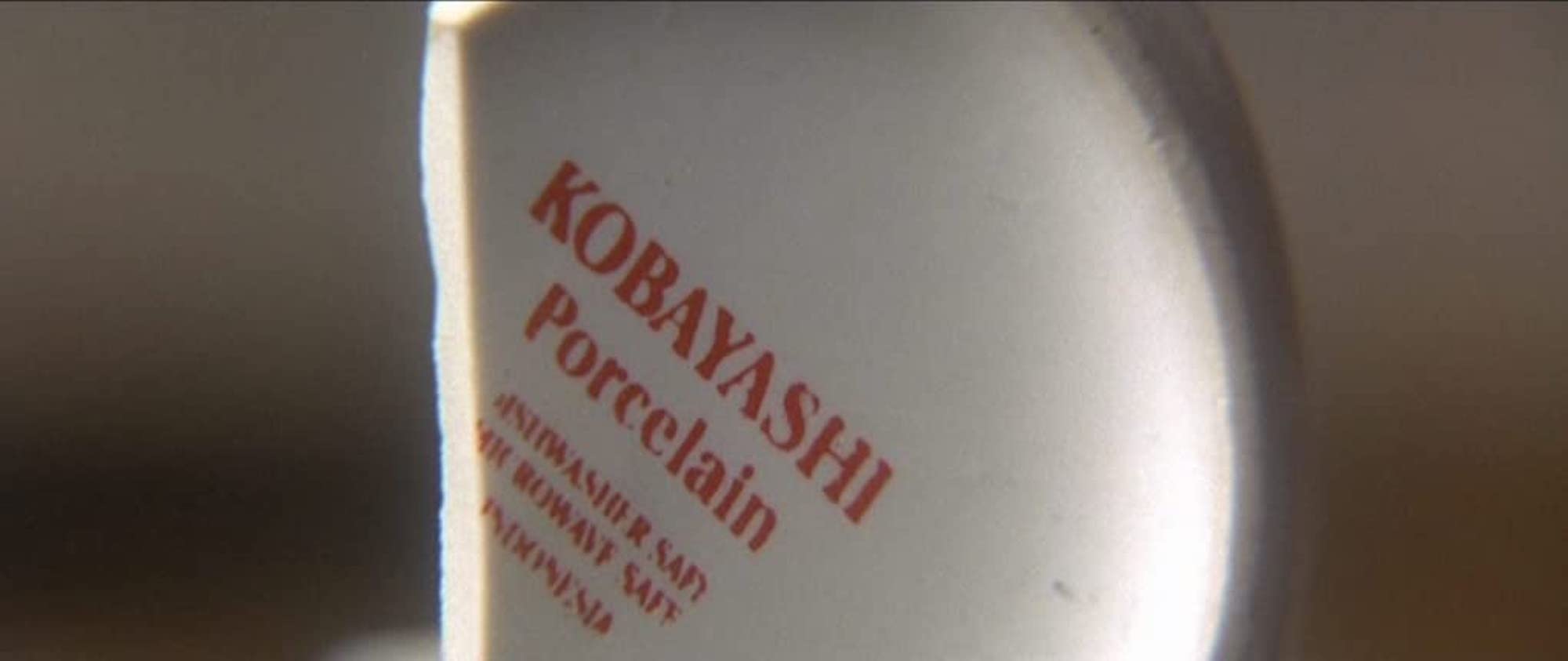

In The Usual Suspects (1995), there’s a scene in which the true extent of ur-villain Keyser Söze’s evil is clarified for the viewer. A gang of Hungarians has burst into Söze’s home and taken his wife and children hostage. “They realized that, to be in power, you didn’t need guns or money or even numbers,” one character, Verbal Kint, narrates. “You just needed the will to do what the other guy wouldn’t.”

The Hungarians want Söze’s territory, and to show how serious their intentions are, one of them slices the throat of Söze’s youngest boy, to the obvious horror of the boy’s mother. The Hungarian grabs Soze’s daughter and makes it clear that she’ll be next.

In response, Söze shoots two of the Hungarians and then does the unthinkable — remember, he’s the bad guy! — and shoots his own children, one by one, and then his wife. Söze tells the Hungarian “he would rather see his family dead than live another day after this.” He lets the last Hungarian go, the better to spread the legend of the villain so heartless he would murder his own family to make a point.

As Verbal puts it: “Keaton always said: ‘I don’t believe in God, but I’m afraid of him.’ Well, I believe in God, and the only thing that scares me is Keyser Söze.”1

Australian regulators have been arguing for months that Facebook derives huge value from the news stories shared on its platform — and that, as a result, Facebook should be forced to compensate the Australian publishers who create them. As with the Hungarians above, Australia’s play can be simplified to: We have something you find incredibly valuable, and unless you give us what we want, we can destroy it.

To which Facebook, by unilaterally banning Australian news stories, responded: You have a really messed up idea of who finds what valuable here. Here, watch me shoot the hostages and show how illusory your “leverage” really is.

It took less than a week for Australia to backtrack. The mandatory arbitration that was the key to Australia’s proposed new law has been reduced to a matter of theory. Facebook can now decide to offer different publishers whatever amount it wants, including nothing at all, without risk of penalty. And Facebook retains the right to shoot more hostages whenever it likes, as Campbell Brown’s statement makes clear:

After further discussions with the Australian government, we have come to an agreement that will allow us to support the publishers we choose to, including small and local publishers. We’re restoring news on Facebook in Australia in the coming days. Going forward, the government has clarified we will retain the ability to decide if news appears on Facebook so that we won’t automatically be subject to a forced negotiation. It’s always been our intention to support journalism in Australia and around the world, and we’ll continue to invest in news globally and resist efforts by media conglomerates to advance regulatory frameworks that do not take account of the true value exchange between publishers and platforms like Facebook.

The money is not and has never been the issue here. Facebook and Google are both perfectly willing to throw money at publishers to hold off regulation. (I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s a petty cash drawer somewhere in Menlo Park labeled Hush Money For Publishers In Anglophone Countries (Small).) As I wrote last year (and, I daresay, it’s held up):

Hence the various Journalism Projects and News Initiatives of Google and Facebook, which started with innovation grants and have since grown to “Okay, we’ll pay publishers some money, fine, but only for this side product that no one really cares about, and we pick who and how much to pay.”From the duopoly’s perspective, the biggest problem with paying for all the news coursing through their digital veins isn’t the money. (They have plenty of money.) It’s that paying for news in any systemic way would attack their core advantage as platforms: organizing other people’s content.

Say you think Google owes The New York Times money for including all of its news stories in search. Fine. Do they also owe me money for including my old blog from the early 2000s? It’s in Google’s index too. How about Breitbart? How about The Daily Stormer or Stormfront? What about your tweets? DairyQueen.com? All of them are digital content that contributes some sort of notional value to Google as a product. Maybe you think you can draw the line somewhere, but where — and how do you apply it to an index of billions of websites?

Should Facebook pay publishers based on how much value they add to News Feed? Okay — then the biggest check goes to the Daily Mail, and The Daily Wire gets as much as The New York Times.

No, any sort of systematic, performance-driven payments to publishers based on the value they offer platforms are a no-go. So Facebook and Google have responded by looking for other ways to deal with the PR headache by getting money to news companies.

The tech giants have money, and they have power. They don’t mind giving up money if it gives them something in return: a friendlier regulatory environment, or silence from cranky publishers. What they don’t want to give up is the power: the power to pick winners (whether via algorithm or cash transfer), the power to decide what it’s willing to pay, and — most importantly — the power to maintain their main advantage as platforms, which is to aggregate huge amounts of free information and profit from all the ways they can organize, distribute, and monetize it all.

If there were suddenly a law that says Google has to pay for some kinds of information in its search index — or that Facebook has to pay to have some kinds of information in News Feed — that core element of their model would be at risk. Suddenly, instead of being a toll road that commuters pay to use, you have to pay drivers for the privilege of using you? That’s the unthinkable.

As Google’s Melanie Silva told Australian officials: “The concept of paying a very small group of website or content creators for appearing purely in our organic search results sets a dangerous precedent for us that presents unmanageable risk from a product and business-model point of view.”

The thing about Keyser Söze vs. the Hungarians is that there’s no side to root for. They’re both bad guys with bad intentions, so instead of some sort of moral valence, all you’re left to compare is the raw power on display from each sides.

Facebook is a corporate nightmare that has done very real and meaningful damage to democracy. Australian regulators carry water for Rupert Murdoch and have been proposing a policy that would, as Tim Berners-Lee says, make the web “unworkable.” But a bad company facing bad regulations distills down to pure power, and by shooting the hostages, Facebook made it very clear where that still lies.

Or, to put it another way: “How do you shoot the devil in the back? What if you miss?”

]

]