Last summer, Vox’s Terry Nguyễn wrote about the ways that our Instagram feeds had changed in the wake of the Black Lives Matters movement. We started to see more PowerPoint-looking slides that were made to communicate information about the protests, and they’ve since been co-opted for just about every subject.

Nguyễn wrote about how those slides, while attention-grabbing, ran the risk of oversimplifying issues, stripping them of their importance, and potentially spreading misinformation:

Coincidental or not, creators are applying this millennialesque visual language to their work, which makes it easy for savvy brands (or anyone who can replicate that design style) to jump on and pervert the movement by using it to further their own corporate mission. Then there’s the question of whether it’s even appropriate to aestheticize these human rights-related issues. As corporations and individuals become attuned to the widespread adoption of memes and certain creative aesthetics in online spaces, they could further be used to “commodify tragedy and obfuscate revolutionary messages,” wrote the Instagram creator @disintegration.loops, later referencing how Breonna Taylor’s death has devolved into a meme.

Most of these activism slideshows don’t appear to be made with malicious intent, nor are they actively harming anyone, but some are worried about the long-term neutralizing effect of making advocacy more digestible and consumable for a large audience.

But slides like these, when done right and with care, make complex stories (about, say, a mutating virus!) more digestible and accessible. At The New York Times, the audience team has been experimenting with variations of these slides and cards on its social media platforms, deputy off-platform editor Jake Grovum said.

“When there’s either an important, complicated news story or something that [would benefit from] context, there’s a real good journalistic reason to do this kind of thing,” Grovum said. “If you look at some of the examples when it works best, it’s almost like you get the first three or four grafs of a news story all in one post. You have the copy of the tweet, a couple of lines in the card, and then it’s just a lot more information and context, and everyone knows that context can be lacking on social.”

At the Times, using slides and cards on social became more of a priority around the beginning of the pandemic last year. The audience team wanted to have a more “visual presence” on Times platforms and wanted to make more use of the maps and data visualizations that lived on the website.

“It all came from wanting to be more visual,” Grovum said. “We made it part of our daily routine to have these visual presences for whatever news or whatever story we’re trying to share.”

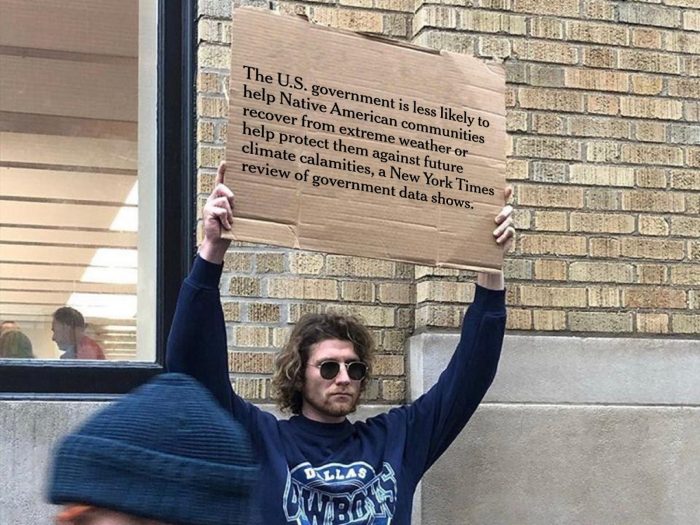

Single cards work better on Facebook and Twitter because those apps don’t have a carousel feature (you know, where you swipe left to see more images in a single post) the way Instagram does. Grovum said he’s found that Facebook and Twitter lend themselves well to text-heavy cards and that users are actually taking the time to read and share them.

The cards have been particularly useful to the Times in debunking misinformation, though Grovum said a broader challenge is designing cards in ways that are still helpful even if they’re screenshotted and stripped of context.

Here, a Facebook post from this past April about a vaccine-related false claim had more than 8,300 shares and 25,000 likes, a sign that users want to share factual information with others.

Compare that to the engagement on another Facebook post from the same day that explains what the word “cheugy” means. Just over a thousand likes and 534 shares.

Grovum said the Times looks at metrics and qualitative feedback (like comments) on the cards as proxy for utility. More engagement is a sign that people found the information helpful, even if they didn’t click the link.

“We’re pretty aware and upfront with ourselves about how these are optimized for off-platform engagement, reach, and sharing. If you wanted to optimize for people clicking through the site, you wouldn’t put a third of the story on a card,” Grovum said. “We’re very aware that there’s a trade-off here, and we’ll usually do bot — we’ll have a link post or something and [also] do the shareable version and get the best of both worlds. Link posts without a visual can drive more actual click-through, [while] the cards are better for engagement.”

Because the text cards are usually image files, they can be difficult to read or even access for people who are visually impaired. Grovum said the Times is still working through those accessibility issues by adding alternative text to some posts, but noted that many social media management tools still don’t have an efficient way of including it, which can cause problems in workflow.

Trying out these new formats is helpful to the Times because it gives journalists a chance to learn about what their audiences want to see.

“Even with templates, these are labor-intensive no matter how easy your processes are. It takes longer to do [a card] than to write a tweet and just get that out,” Grovum said. “But I think it pays off to understand your audience and lean into things that you know are going to resonate with them.”