“You Americans, you’re so obsessed with those mountains of facts,” was the response I recall during the early days of our efforts to establish an international investigative network, back in the days before the internet.

The voice on the other end was Nils Gunnar Niilson, editor of Sydsvenska Dagbladet, a leading newspaper in southern Sweden. Niilson, like many of the other European editors we worked with, did not have an aversion to “facts.” In fact, he sought them out from U.S. and his own team of reporters. It was more about their placement — where they appear in the architecture of an investigative story. From his point of view, we Americans delivered them too early, too quickly, just blasted away with the juicy findings and then other details faded down the descending steps of the inverted pyramid.

That was one of the early memorable calls in our effort almost 40 years ago to establish what may have been the world’s first international investigative network. It was a common observation: U.S. investigative reporting did not have the more literary ways of delivering revelations that was more characteristic of European journalism, where context, to put it broadly, preceded conclusion.

That was back in the days before the internet had blurred some of the stylistic distinctions across national frontiers, and sophisticated data-sharing techniques had helped make collaborations, like the path-breaking global investigations of the past 10 years, more common. But one thing we shared: The power of investigative journalism to follow power and centers of influence across national frontiers.

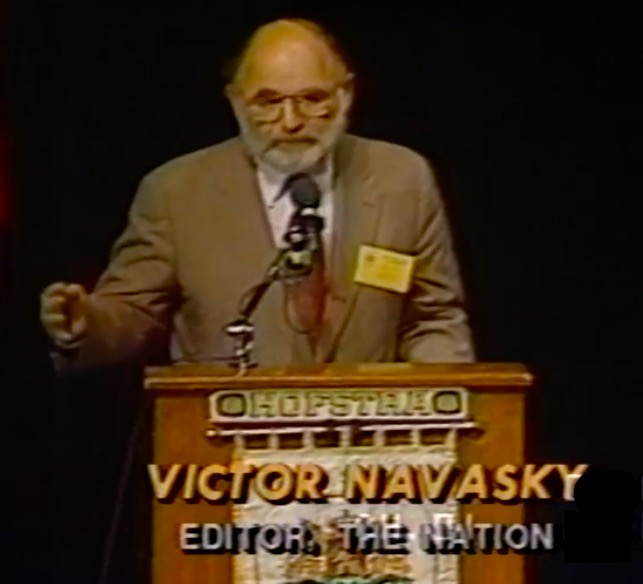

Back in 1986, Victor Navasky, the then-editor of The Nation, a liberal U.S. news and opinion magazine, had an inspired idea. For more than 150 years, the magazine, the oldest weekly publication in the United States, had produced generations’ worth of great journalism by some of the nation’s finest journalists, with a reputation for challenging the status quo.

InterNation was born out of an idea by the then-editor of The Nation, Victor Navasky, seen here at a 1988 symposium on the US presidential election. Screenshot via C-SPAN.

Navasky, who came to The Nation with an already storied history as a writer and editor in magazine journalism, was in touch with his counterparts at like-minded publications abroad — the feisty weeklies and dailies that boosted investigative journalism. Most, in those days, were in what was known as Western Europe and some new publications arising from the newly free democracies in Latin America. Why not find a way to collaborate on stories of common interest?

Publications were, of course, fiercely competitive in their national markets. But they wouldn’t be competing in foreign markets. As corporate power and criminal gangs started moving ever more frequently across national frontiers, why not cooperate to track and expose them? This may seem highly obvious today, but back then this was a radical new idea.

In those days, it’s not as if you could fire off an email to someone to test out an idea. And transatlantic phone calls were insanely expensive. The only way to build this network was very old-fashioned — in person. Amazingly, Victor asked me if I’d be interested. I was in my late 20s, hardly a seasoned journalist, but had long been interested in the global dimension to stories. I used to seek out foreign magazines or compilations of translated global newspapers and had spent time reporting in Europe and Mexico. I had landed a job as a junior reporter at the recently founded Center for Investigative Reporting, where the two co-founders provided on-the-job training in the methods of investigative journalism. I’d written a couple of stories for The Nation, and co-authored a book, Circle of Poison, (with CIR’s co-founder David Weir) that exposed the dumping of banned pesticides in developing nations. Reporting that book taught me how to follow a trail of evidence across borders, and that an abundance of international sources could be found if you knew where to look. I had a cockeyed optimism that such a scheme could work. I’d taken a college semester of French. I said yes, and moved to Paris a couple of months later. InterNation was born.

Over a series of meetings with Victor, sometimes over a tumbler or two of vodka, we concocted a plan. My pal Phillip Frazer, a genius in the publishing business, would be my partner in New York. (He would go on to found several feisty newsletters on political corruption and the environment that would succeed in being both profitable and journalistically groundbreaking; one of them, the Hightower Lowdown, is now on Substack.) He handled all the logistics of the operation. My job would be to meet with editors abroad, explain our vision of collaborative publication for stories of mutual interest, seek out writers, and give the stories an initial edit before sending them off to The Nation’s then-foreign editor George Black (who most recently authored a celebrated book on Vietnam). Hamilton Fish, then-publisher of The Nation (now publisher of the Washington Spectator) suggested we launch the project with an international conference.

We had our first InterNation conference in Amsterdam in the spring of 1987, co-hosted by the Dutch weekly Vrij Nederland and its editor Rinus Ferdinandusse, who joined out of a sense of open-mindedness and curiosity about what would happen when a bunch of investigative journalists and editors were lured to Amsterdam. Phillip saved a cassette recording of that launch conference, where we can hear, on scratchy 36-year-old audio, Victor launching the proceedings with an acknowledgment of how unlikely it was to even think of a collaborating network of international investigative journalists. (Phillip, I discovered, also collected and saved some of the letters I sent back to him reporting on our progress — and on which some of these recollections are based.) Victor’s comments, at our inaugural gathering held in the Flemish Cultural Center in Amsterdam, capture the time in which the idea of journalists sharing information and collaborating on trans-national investigations was, shall we say, not exactly in the zeitgeist.

“Investigative journalists,” Victor said, “are by definition loners, non-cooperative, double agents, they don’t share information. They have a talent for not letting anyone know what they’re about. They are underfunded, they may not take well to directions.” You can hear the nervous laughter flickering across the room. And, he said, they contend with wary editors, “who are suspicious [of what they’re doing] when they’re off-site.”

Thus, he introduced the four editors on our opening panel: Ferdinandusse, of Vrij Nederland; John Lloyd, of the British weekly The New Statesman; Peter Wivel, of the Danish weekly Information; and Nils Gunnar Niilson of Sydsvenska Dagbladet. Victor moderated (listen to the audio clip here). All seemed to viscerally understand the importance of journalists developing the skills to follow money, power, and corporate influence across national frontiers — and that collaboration might be a way to do so. But how to do it? Over numerous meetings and cocktails, a rough plan was hammered out: Stories would run in roughly the same one to two-week timespan. Editors could tailor them to their national audiences as they saw fit. The Nation would conduct the fact-checking. Each story would run with a tagline, “An InterNation Story” (a provision not, alas, religiously followed). My job was to follow up, find the writers, and make the stories happen.

At that conference we also made another kind of history, with our keynote speaker, I. F. Stone, the legendary U.S. journalist, making his final public speech. In journalistic circles, I. F., or Izzy, Stone is renowned for starting the first investigative newsletter in the United States, I. F. Stone’s Weekly. Notably, he launched the Weekly in 1953 the same week that Joe McCarthy became chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, from which the senator launched his notorious anti-communist campaign of terror. It quickly became clear that Izzy had forged a new way of doing investigations. Pugnacious and alone, he broke many of the big stories from the 1950s into the early 1970s, often by following paper trails, and released them through his own outlet every week. That included numerous scoops and criticisms of the war in Vietnam.

By the 80’s, Izzy himself was in his 80s, and had only one request when Victor asked him to speak abroad: He didn’t like flying and asked if he could be sent to Europe by boat. A cabin for he and his wife was booked on the transatlantic ocean liner, the Queen Mary, an unusual indulgence by The Nation out of respect for this living legend of investigative journalism. Into the port of Rotterdam sailed Izzy a day before our conference commenced.

The first issue of I. F. Stone’s Weekly, which heralded a new kind of investigative journalism in the U.S.

From Phillip Frazer’s recording of Stone’s speech that day, we can hear through the crackling audio, his genial and even bemused exhortations to the assembled editors and journalists. Stone was philosophical: “We journalists are under constant pressure to provide meaning,” he told the crowd. And he was grounded in the practical: “Read the newspaper from the back to the front,” he said, because for investigative journalists that’s where the stories are. “In those back pages, you can see all the ‘little’ items that got overlooked in the front pages…because they have the seeds of disagreement with the conventional wisdom.”

His technique, he said, would be to get the corresponding backstory to all those front-page stories. A coup in Bolivia? His first stop was to get data not from the State Department but from the Bureau of Mines, to understand which mining companies were operating there and obtain clues as to who had stakes in the coup. An underground nuclear bomb test? He didn’t join the delegation of embedded journalists invited to witness it in Nevada, but tracked down the seismographers in Japan and Canada who told him that the shocks from the explosions registered on their seismographs and could be felt thousands of miles away, and not just the 200 miles that the Pentagon claimed.

There was, Stone noted, little sense of collaboration among international journalists back then (listen to a clip here). He regretted not having a network of like-minded publications to work with on what could have been a “big global story,” like the effort to ban underground nuclear tests, which the Pentagon claimed would be unverifiable. “If there had been an InterNation at that time, an international collaboration among radical journalists, the outcome might have been very different,” he lamented. Scoops could be shared, he said, and built upon. “That’s why I think InterNation is a great idea,” he would go on to say.

And thus, Izzy Stone anointed our fledgling enterprise.

For the next three years, we tried to put that spirit into practice. I shared an office with a film production company in Paris and spent, it seemed, half my time standing in front of a fax machine, either feeding in stories to all of our collaborating outlets, or receiving back commentaries on them. We found writers, many based in Europe for whom The Nation might as well have been a publication on Mars; and some Americans, for whom the reverse was true among our many European publications. But the results started coming in.

Within a year, we had several stories published or underway. Some of those path-breaking investigations included: the U.S. right-wing’s aggressive expansion into Europe and their connections with neo-fascist organizations; an investigation into how the then-Reagan administration was pressuring European governments to deploy U.S. nuclear missiles and its Star Wars technology; the international arms trade with Iran, mostly centered in Belgium; the export of global hazardous wastes to developing countries; and the connection of U.S. political figures to the recently deposed right-wing military government in Argentina.

The stories, reported and written by journalists based in Europe, the U.S., and Latin America, were published in more than a dozen international outlets. Along with The Nation in the U.S., we ran exposés in: The New Statesman (U.K.), Vrij Nederland (Netherlands), De Morgen (Belgium), L’Evénement du Jeudi (France), Dagens Nyheter and Sydsvenska Dagbladet (Sweden), Information (Denmark), Helsingin Sanomat (Finland), Tageszeitung (Germany), Tages Anzeiger (Switzerland), L’Espresso (Italy), Proceso (Mexico), and El Periodista (Argentina). We assumed the translations and alterations in style were accurate; relationships, like today, were based on trust. Often staff journalists would expand upon the story with deeply reported companion pieces, giving them a deep sense of local connection.

An example of InterNation’s low-tech correspondence in 1986 between Schapiro, in Paris, and Frazier, his U.S. editor in New York, which in this case involved typing a message directly onto an air-mailed letter called an Aerogramme.

A year later, in 1988, we held a follow-up conference in London and our network had grown to 65 journalists and editors. By 1991, when we held our final conference in Moscow, the world had radically changed. The Berlin Wall had fallen. East European countries had bolted from the Soviet orbit and would, soon enough, apply for membership in the EU. Russia itself was in the throes of the early days of perestroika and glasnost. Katrina vanden Heuvel, then a young rising star at The Nation, and who would later succeed Victor as editor, corralled her deep contacts in Russia to help U.S. organize an extraordinary event — bringing together the nascent Russian press with their global counterparts.

At the time, Russia was bursting with new publications: Ogonyok, Nezavisimaya Gazeta, and others; even Pravda was being refashioned in the spirit of the times. The editors and journalists from those and other publications and TV stations from the suddenly blossoming Russian press engaged with their Western European counterparts over an extraordinary couple of days. Freed from the yoke of censorship, that country’s publications were on a roll — investigating everything from the theft of public properties to the corruption of the crumbling Communist Party. One heated ethical discussion focused on whether it was acceptable to pay for information. It was eye-opening to many of the journalists assembled to hear top Russian editors discounting “Western” objections to such a practice. In Russia, where the economy was teetering due to the colossal changes underway, one would never get a story without providing some kind of payoff, even small, to sources, they explained. The Nation and many other members of the network started collaborating in a more direct way — syndicating stories that offered a glimpse into the dramatic changes underway in Russia and Eastern Europe. (All of the publications, TV stations, and radio programs that were present at that year’s conference have either been forced to close by the government, driven out of the country, or, like Pravda transformed back into pro-government propaganda.)

A five-page memo that details the early history of the InterNation collaborative journalism network, as well as a summary of events at InterNation’s second conference, held in London, England, in 1988. Click here to see more of the memo. Via Philip Frazier.

As for InterNation, the money, as it often does, started running out. I left Paris and returned to the U.S. to take a job at Mother Jones. The legendary investigative journalist Mark Dowie took over InterNation in a scaled down form from his home in northern California. Two notable investigations resulted in that final year: one was an exposé of the global cement cartel; the other on the secret teams dispatched by the U.S. to monitor Communist Party members in Western Europe.

By 1992, the loose network we’d created went onto take other forms — mostly shared stories and translations. As Dowie put it, “a syndicate arose from the syndicate.” As it happens, Dowie’s upcoming book on the history of investigative journalism, When Truth Mattered: History and Spirited Defense of Investigative Journalism from 445 B.C. to the Present, goes into considerable detail on the evolution of this collaborative spirit. (It will be published next year by New York University Press.)

It would have been hard to imagine back then just how much the universe of cross-border collaborations would explode. As globalization took hold in journalism — in a world no longer dominated by Cold War divisions — the internet offered instantaneous communications, while the skills of journalists in accessing and analyzing international data leapt to levels of the Panama Papers and beyond. The incredible power of collaborations is exemplified by the many investigative networks — global, national, regional — now present within GIJN, at a scale we never could have envisioned more than three decades ago. Some of those were early pioneers back in the day with InterNation (they know who they are).

The changes have been profound, but the words of I. F. Stone to that Amsterdam conference continue to resonate, as much with the current Global Investigative Journalism Network as with our merry band 35 years ago. You can hear Stone’s wily sense of humor in the scratchy recording, a message to new generations of investigative journalists that will no doubt echo through the ages. Step one, he said: Discount the common wisdom. Step two: “Investigative journalists should use their heads for more than just carrying a hat.”

Mark Schapiro is an investigative journalist and author specializing in the environment. His most recent book is Seeds of Resistance: The Fight for Food Diversity on Our Climate-Ravaged Planet. This story was originally published by the Global Investigative Journalism Network and is used here under a Creative Commons license.