There is a flaw in the investigative reporting model and it has to do with longevity. Follow me on this for a second: A reporter works months at a time scouring documents, meeting sources, verifying details, writing, and perhaps even building a database. And then the piece is published.

And that’s it.

The lifespan of investigative reporting, at least as it’s typically done through newspapers, can be disappointingly short given the painful labor and birthing process. Once stories are released, the hope is the public (or perhaps lawmakers) will pick up the torch to right the wrongs illuminated by reporters. But the drumbeat stops after a while. Reporters have to move on to new assignments, and the public’s desire to change laws and right wrongs can be overtaken by things like #Winning.

In an ambitious new project, the Center for Public Integrity, Public Radio International, and Global Integrity are trying to build a new mechanism that keeps the intensity and awareness of investigative reporting at a steady pace.

What they’re building is a fifty-state corruption risk index. Think of it like a Homeland Security threat level indicator that shows just how susceptible your state is to corruption. Already this is no small task: They plan to hire a reporter in each state to do ground-level reporting and compile information for the index as well write stories. Where they hope to transform the investigative reporting machine, though, is by going transparent and getting people invested in the project before it officially drops next year. Instead of holding onto information before the project is complete, they’ll invite the public in, ask for a little crowdsourcing, and build momentum — and a network. The goal is to make the corruption index something of a perpetual motion machine.

“The idea here is that in recent years really good, solid investigative reporting on the state level has fallen off, and state newspapers have had to make cutbacks,” said Caitlin Ginley, the project coordinator for CPI. “We see this as a great way to revitalize that.”

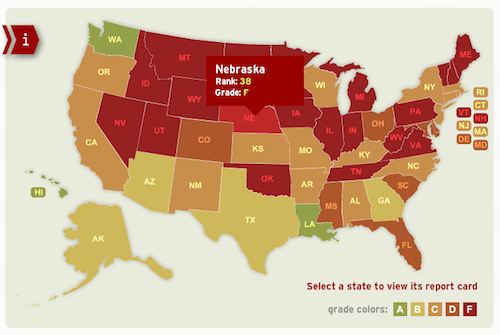

The corruption index is not without some precedent. In 2009, The Center for Public Integrity released States of Disclosure, a fifty-state ranking of financial disclosure laws for local legislators (and source for the map above). Ginley told me they wanted to build on that foundation for the corruption index, using financial disclosure laws, conflict-of-interest laws, FOIA regulations, lobbyist rules, and other accountability standards as indicators to gauge the likelihood of corruption.

“Reporters can take that information and see this is where [their state is] doing very poorly and report that out,” Ginley said.

In its role, Global Integrity will help by creating a methodology and guiding the analysis of the data that comes in. (Reporters will also be using Global Integrity’s Indaba tool to collect and publish information.) The end result will be much like States of Disclosure, with report cards and rankings, as well as background data from each state, Ginley said.

But the work that starts now, aside from the hiring of journalists in each state (JOB ALERT), is identifying people or organizations who can be helpful over the course of the corruption project.

“We have the tools now for people to get engaged in stories as they go along and that creates a lasting commitment so its not a one-shot deal,” said Michael Skoler, vice president of Interactive Media for PRI. Just as important as finding reporters and document-hounding is cultivating a community that can guide and assist the reporting, Skoler told me. (Skoler is familiar with the concept, having established the Public Insight Network while working for American Public Media.)

“The standard mode for investigative reporting is that people don’t talk at all about what they’re doing,” he told me.

PRI will work with its more than 800 partner stations to find expertise and build interest in the project over the next twelve months so that ideally, when the report is produced, there will be a built-in audience who can share it with others or try to minimize corruption in their state. Projects around government and budgets are ripe conditions for crowdsourcing, but Skoler thinks the crowdsourcing concept is something far too many people attempt but ultimately don’t understand.

“I think one of the misconceptions about crowdsourcing is when you crowdsource, you’re trying to attract and engage everyone. And that doesn’t work,” Skoler said. “Crowdsourcing is about reaching out to the people who are naturally interested and knowledgeable about something and inviting them to play.”

Within each state, he points out, there are honest government/open government groups, think tanks, academics, and non-profits who have an interest in state corruption and could assist in the project. Skoler thinks approaching these specific people and groups, unlike asking the general readership for help, could produce better results.

He also things that approach could help to increase the reach of investigative reporting. Instead of hoping that the results a reporter produces will automatically take on a life of their own, the corruption index hopes to apply strategy to extending the shelf life of accountability journalism. As Skoler puts it, “It’s a new way of thinking about impact for investigative journalism — and about building impact in through a whole process.”