Blogs and newspaper sites enjoy a built-in advantage when it comes to search-engine optimization. They deal in words. But a whole universe of audio and video content is practically invisible to Google.

Say I want to do research on Osama bin Laden. A web search would return news articles about his assassination, a flurry of tweets, the Wikipedia page, Michael Scheuer’s biography, and an old Frontline documentary, “Hunting Bin Laden.” I might then take my search to Lexis Nexis and academic journals. But I would never find, for example, Frontline’s recent reporting on the Egyptian revolution, where bin Laden makes an appearance, or any number of other video stories in which the name is mentioned.

While video and audio transcripts are rich for Google mining, they’re also time-consuming and expensive. PBS is out to fix that by building a better search engine. The network has transcribed and tagged, automatically, more than 2,000 hours of video using software called MediaCloud.

“Video is now more Google-friendly,” said Jon Brendsel, the network’s vice president of product development. Normally, automatic transcription is laughably bad — Google Voice users know this — but Brendsel is satisfied with the results of PBS’ transcription efforts. He said the accuracy rate is about 80 to 90 percent. That’s “much better than the quality that I normally attribute to closed captioning,” he said. The software can get away with mistakes because the transcripts are being read by computers, not people. (For a hefty fee, the content-optimization platform RAMP will put its humans to work to review and refine the auto-generated transcripts.)

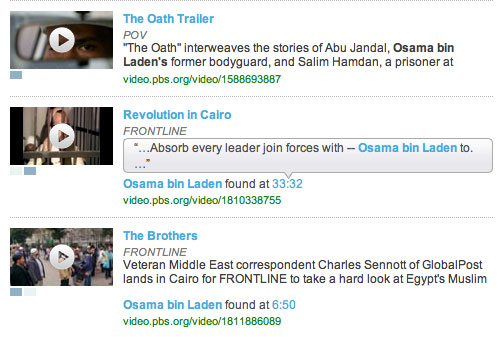

Query “Osama bin Laden” at PBS’ video portal, and the new search engine returns videos in which the phrase appears, including time codes. “Osama bin Laden found at 33:32,” reads one result. (So that’s where he was?) Mouse over the text to see the keyword in context; click it to be deposited at the precise moment the keyword is spoken. (Notice the text “Osama bin Laden” appears nowhere on the resulting page.)

PBS’ radio cousin, NPR, still relies on humans for transcription, paying a third-party service to capture 51 hours of audio a week. In-house editors do a final sweep to ensure accuracy of proper names and unusual words. It’s expensive, though NPR does not disclose how much, and time-consuming, with a turnaround time of four to six hours.

“We continue to keep an eye on automated solutions, which have gradually improved over time, but are not of sufficiently high quality yet to be suitable for licensing and other public distribution,” said Kinsey Wilson, NPR’s head of digital media.

Despite the expense, NPR decided to make all transcripts available for free when relaunching its website in July 2009. “Transcripts were once largely the province of librarians and other specialists whose job was to find archival content, often for professional purposes,” Wilson said at the time. “As Web content becomes easier to share and distribute, and search and social media have become important drivers of audience engagement, archival content — whether in the form of stories or transcripts — has an entirely different value than it did in the past.”

Put another way: Readers today (kids today!) are accustomed to search as a shortcut to obtaining information. If Google doesn’t index your content, it might as well not exist. (And there are other emerging platforms in the layering-text-on-video game — Universal Subtitles, for example, which essentially crowdsources captioning efforts.) Brendsel said mass indexing is a much more complicated project for PBS, because PBS does not own its content, unlike NPR. The network has to work out rights with multiple producers. And the transcription software is also expensive, he said. PBS is still working out a financial model for extending this service to local stations.

Brendsel plans to offer human-readable transcripts on story pages soon, when the video portal gets a design refresh. That will be the final step in making PBS video truly Google-friendly, allowing search engines to to crawl its text.