![]() Every Friday, Mark Coddington sums up the week’s top stories about the future of news.

Every Friday, Mark Coddington sums up the week’s top stories about the future of news.

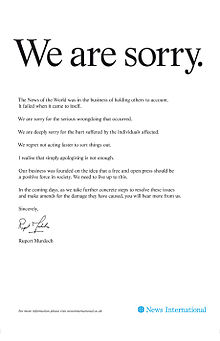

News Corp.’s scandal keeps growing: Rupert Murdoch might have hoped News Corp.’s phone hacking scandal would die down when he closed the British tabloid News of the World last week, but it only served to fuel the issue’s explosion. This past week, the scandal’s collateral damage spread to News Corp.’s proposed takeover of the British broadcaster BSkyB: Faced with increasing pressure from the British government and the revelation that News Corp. journalists tried to get private records of former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, News Corp. dropped the BSkyB bid, which had been a huge part of the company’s U.K. strategy. (And the scandal only grew worse over the weekend, with the arrest of resigned News Corp. exec Rebekah Brooks and the resignation of the head of Scotland Yard.)

Plenty of other problems are cropping up for News Corp., too. The top lawyer for its U.K. newspaper branch, News International, quit. The company’s stock lost $7 billion in four business days at one point. A pre-existing U.S. shareholders’ suit expanded to cover the hacking scandal. The Murdochs have to testify before British Parliament this week about the scandal, and the FBI started investigating U.S.-related aspects of the issue. That’s all in addition to the ongoing problems News Corp. faces, as detailed by Poynter’s Rick Edmonds.

Plenty of other problems are cropping up for News Corp., too. The top lawyer for its U.K. newspaper branch, News International, quit. The company’s stock lost $7 billion in four business days at one point. A pre-existing U.S. shareholders’ suit expanded to cover the hacking scandal. The Murdochs have to testify before British Parliament this week about the scandal, and the FBI started investigating U.S.-related aspects of the issue. That’s all in addition to the ongoing problems News Corp. faces, as detailed by Poynter’s Rick Edmonds.

The scandal has led quite a few writers to criticize the culture that Murdoch has created at News Corp. Capital New York’s Tom McGeveran and Reuters’ John Lloyd railed on Murdoch and News Corp.’s character, Carl Bernstein called this Murdoch’s Watergate, and the Observer’s editorial board called for systemic reforms in Britain so Murdoch’s influence can never be so strong. Members of the Bancroft family said they wouldn’t have sold the Wall Street Journal to Murdoch in 2007 if they’d have known the hacking was going on.

On the other hand, The New York Times pointed out that sleazy British tabloid tactics are hardly limited to Murdoch, and media critic Howard Kurtz noted that they’re very much alive in the U.S. mainstream press, too. New York Times columnist Roger Cohen defended Murdoch, saying he’s been good for journalism on the whole, and Gawker’s John Cook defended those tabloid reporting tactics. Meanwhile, j-prof Jeff Jarvis and the Telegraph’s Toby Harnden urged the British government not to respond by enacting more regulation.

News Corp.’s retreat might not stop with News of the World and BSkyB. Murdoch biographer Michael Wolff and others have reported that the company’s execs are debating whether to get out of Britain’s newspaper business entirely, and several observers chimed in to say that might actually make a good deal of business sense. Media analyst Ken Doctor said News International is losing steam, and the Financial Times’ John Gapper said newspapers are becoming far more trouble than they’re worth to Murdoch.

Not only that, but the New Yorker’s John Cassidy said dropping his U.K. newspapers could let Murdoch revive his BSkyB bid, and Jeff Jarvis speculated that when Murdoch chooses between the power that the papers give him and the money saved by getting rid of them, he’ll choose the money. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal, Murdoch called the rumors of a newspaper sell-off “rubbish.”

But just because News of the World and News International may be dead and dying, that doesn’t mean newspapers as a whole are, argued David Carr of the New York Times. As he noted, it was the Guardian’s dogged reporting that finally broke this story open. Murdoch “prefers his crusades to be built on chronic ridicule and bombast. But as The Guardian has shown, the steady accretion of fact — an exercise Mr. Murdoch has historically regarded as bland and elitist — can have a profound effect,” Carr wrote. The Atlantic also had praise for the Guardian, and Poynter’s Mallary Jean Tenore interviewed one of its editors about the lonely journey of covering the phone hacking story.

HuffPo aggregation under the microscope: A lively discussion about the rights and wrongs of aggregation developed last week out of a column by Ad Age media critic Simon Dumenco, who complained that the Huffington Post had extensively summarized one of his posts, buried the link to the original, and — contrary to Arianna Huffington’s argument that her site benefits those they aggregate by sending them readers — gave him just 57 pageviews.

![]() The Huffington Post responded by apologizing and suspending the article’s writer. HuffPo business editor Peter Goodman told Adweek the piece was a fully formed article when it should have been a simple introduction and a link, but Dumenco responded to the apology by arguing that the writer did nothing out of the ordinary — this is just how HuffPo tells its writers to do it.

The Huffington Post responded by apologizing and suspending the article’s writer. HuffPo business editor Peter Goodman told Adweek the piece was a fully formed article when it should have been a simple introduction and a link, but Dumenco responded to the apology by arguing that the writer did nothing out of the ordinary — this is just how HuffPo tells its writers to do it.

Dumenco’s point was echoed by several others: The Awl’s Choire Sicha said the suspended writer was doing what she was taught, Gawker’s Ryan Tate, drawing on a revealing quote from a former HuffPo writer, made the same point: “This is pretty ridiculous, given HuffPo’s systematic, officially-sanctioned approach to rewriting too much of people’s news articles.” U.K. journalist Kevin Anderson called HuffPo’s summary-heavy aggregation “a pretty cynical strategy,” and paidContent’s Staci Kramer said HuffPo needs to respect its sources, rather than treating a link as a favor.

Gabe Rivera, whose news site, Techmeme, was compared to HuffPo favorably by Dumenco, looked for terms to distinguish what his site does from what HuffPo does. Poynter’s Julie Moos said some measure of originality will always make for better journalism and a better business model than heavy aggregation, and ZDNet’s Tom Foremski pined for the old blogging mentality whose goal was to add value. In a short podcast, author Steven Rosenbaum said this is a logical time to step back and evaluate exactly what constitutes ethical aggregation.

There were a few dissenters, though: GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram and Slate’s Jack Shafer both argued that the type of aggregation that HuffPo does has been around for ages in traditional media (especially in Britain, according to Forbes’ Tim Worstall). In fact, Shafer said, news orgs could learn a something valuable from the Huffington Post: “That a huge, previously ignored readership out there wants its news hot, quick, and tight.”

Comparing Google+, Facebook, and Twitter: It’s been just about three weeks since Google+ launched, and Google’s new social network is growing like a weed, with 10 million users shared so far. (Its number of active users may soon be approaching Twitter’s figures.) Google+ news has dominated Twitter, and Google’s also working on integrating it with Gmail.

With Plus’ incredible growth, tech observers have been going back and forth about what social network Google+ is disrupting most. PCWorld’s Megan Geuss wondered whether Google+ and Facebook can coexist, and PC Magazine’s John Dvorak posited that all the excitement about Google+ is more or less just pent-up frustration with Facebook. The New York Times’ David Pogue and Technology Review’s Paul Boutin both compared Google+ favorably to Facebook, largely because of its superior privacy controls (though GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram pointed out that it may not be a privacy improvement for some people).

With Plus’ incredible growth, tech observers have been going back and forth about what social network Google+ is disrupting most. PCWorld’s Megan Geuss wondered whether Google+ and Facebook can coexist, and PC Magazine’s John Dvorak posited that all the excitement about Google+ is more or less just pent-up frustration with Facebook. The New York Times’ David Pogue and Technology Review’s Paul Boutin both compared Google+ favorably to Facebook, largely because of its superior privacy controls (though GigaOM’s Mathew Ingram pointed out that it may not be a privacy improvement for some people).

Meanwhile, Search Engine Land’s Danny Sullivan said Google+ is more comparable to Twitter, then went ahead and made a thorough, smart comparison between the two. The Atlantic’s Alexis Madrigal said Google+ might end up being more conversational than Twitter, which he called more of a call-and-response: Google+ “won’t be as good at connecting people to information or each other quickly, but it might be better at longer form discussions and whatever we call the process by which people pull reasoned thoughts from their networks into public discourse.” Hutch Carpenter said Google+ resembles both Facebook and Twitter, and Computer World’s Mike Elgan wrote that it’ll disrupt just about everything.

Still, Google+ has its limits: ReadWriteWeb’s Marshall Kirkpatrick explained why he’d never move his personal blog there as some are doing, and Instapaper’s Marco Arment and the Guardian’s Dan Gillmor both urged readers to keep a space for their own online identity outside of spaces like Google+ or Facebook. For journalists feeling out Google+, Meranda Watling of 10,000 Words put together a preliminary guide.

Reading roundup: Here’s what else people were talking about this past week:

— The newspaper chain MediaNews made a distinctive play for the tablet news market last week, announcing the launch of TapIn, a location-based news app made specifically for tablets. It’ll start in the Bay Area in partnership with the San Jose Mercury News. Ken Doctor, Jeff Sonderman, and Mathew Ingram all wrote about what makes it worth watching.

— The Economist continued running pieces all week in its series on the future of the news industry. You can check out several writers’ reasons for optimism or read the opening statements in an ongoing debate between NYU’s Jay Rosen and author Nicholas Carr about whether the Internet has been good for journalism.

— Boston Globe developer Andy Boyle made his pitch for young journalists to go into web development, or as he put it, “learn to make the internets.”

— Poynter’s Jeff Sonderman put together two great social media how-to’s for journalists: One on verifying information on social media, and the other on strategies for engagement on Facebook.

— Finally, NYU’s Clay Shirky gave us another thoughtful essay on the unbundling of news and why the news ecosystem needs to be chaotic right now. In the end, though, here’s what he believes news should be: “News has to be subsidized because society’s truth-tellers can’t be supported by what their work would fetch on the open market”; “news has to be cheap because cheap is where the opportunity is right now”; and “news has to be free, because it has to spread.”