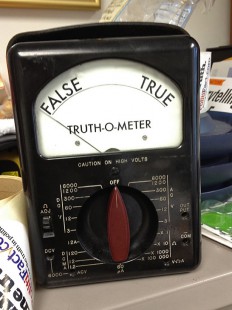

WASHINGTON — PolitiFact’s “Star Chamber” is like Air Force One: It’s not an actual room, just the name of wherever Bill Adair happens to be sitting when it’s time to break out the Truth-O-Meter and pass judgment on the words of politicians. Today it’s his office.

Three judges preside, usually the same three: Adair, Washington bureau chief of the Tampa Bay (née St. Petersburg) Times; Angie Drobnic Holan, his deputy; and Amy Hollyfield, his boss.

For this ruling — one of four I witnessed over two days last month — Holan and Hollyfield are on the phone. Staff writer Louis Jacobson is sitting in. Jacobson was assigned to check this claim from Rep. Jeff Duncan (R-S.C.):

83% of doctors have considered leaving the profession because of

#Obamacare#repealandreplace— Jeff Duncan (@Duncan4Congress) July 10, 2012

After conducting five interviews, poring over survey data, and filing 1,100 words, Jacobson is recommending False. Hollyfield wants to at least consider something stronger:

Hollyfield: Is there any movement for a Pants on Fire?

Adair: I thought about it, but I didn’t feel like it was far enough off to be a Pants on Fire. What did you think, Lou?

Jacobson: I would agree. Basically it was a case I think of his staff blindly taking basically what was in Drudge and Daily Caller. Should they have been more diligent about checking the fine print of the poll? Yes, they should have. Were they being really reckless in what they did? No. It was pretty garden-variety sloppiness, I would say. I don’t think it rises to the level of flagrancy that I would think of a Pants on Fire.

Adair: It’s just not quite ridiculous. It’s definitely false, but I don’t think it’s ridiculous.

This scene has played out 6,000 times before, but not in public view. Like the original Court of Star Chamber, PolitiFact’s Truth-O-Meter rulings have always been secret. The Star Chamber was a symbol of Tudor power, a 15th-century invention of Henry VII to try people he didn’t much care for. While the history is fuzzy, Wikipedia’s synopsis fits the chamber’s present-day reputation: “Court sessions were held in secret, with no indictments, no right of appeal, no juries, and no witnesses.”

PolitiFact turns five on Wednesday. Adair founded the site to cover the 2008 election, but the inspiration came one cycle earlier, when a turncoat Democrat named Zell Miller told tens of thousands of Republicans that Sen. John Kerry had voted to weaken the U.S. military. “Miller was really distorting his record,” Adair says, “and yet I didn’t do anything about it.”

The team won a Pulitzer Prize for the election coverage. The site’s basic idea — rate the veracity of political statements on a six-point scale — has modernized and mainstreamed the old art of fact-checking. The PolitiFact national team just hired its fourth full-time fact checker, and 36 journalists work for PolitiFact’s 11 licensed state sites. This week PolitiFact launches its second, free mobile app for iPhone and Android, “Settle It!,” which provides a clever keyword-based interface to help resolve arguments at the dinner table. (PolitiFact’s original mobile app, at $1.99, has sold more than 24,000 copies.) The site attracts about 100,000 pageviews per day, Adair told me, and that number will certainly rise as the election draws closer and politicians get weirder.

If your job is to call people liars, and you’re on a roll doing it, you can expect a steady barrage of criticism. PolitiFact has been under fire practically as long as it has existed, but things intensified earlier this year, when Rachel Maddow criticized PolitiFact for, in her view, botching a series of rulings.

In public, Adair responded cooly: “We don’t expect our readers to agree with every ruling we make,” is his refrain. In private, it struck a nerve.

“I think the criticism in January and February, added to some of the criticism we’ve gotten from conservatives over the months, persuaded us that we needed to make some improvements in our process,” Adair told me. “We directed our reporters to slow down and not try to rush fact-checks. We directed all of our reporters and editors to make sure that [they’re] clear in the ruling statement.”

Adair made a series of small changes to tighten up the journalism. And for the first time he invited a reporter — me — to watch the truth sausage get made.

To understand fact-checking is to accept a paradox: “Words matter,” as PolitiFact’s core principles go, and “context matters.”

Consider this incident recently all over the news: Harry Reid says some guy told him Mitt Romney didn’t pay taxes for 10 years. It’s probably true. Some guy probably did say that to Harry Reid. But we can’t know for sure. To evaluate that statement is almost impossible without cooperative witnesses to the conversation.

Now, is Reid’s implication true? We can’t know that, either, not until someone produces evidence. So how does a fact checker handle this claim?

The Truth-O-Meter gave Reid its harshest ruling, “Pants on Fire,” a PolitiFact trademark reserved for claims it considers not only false but absurd. In the Star Chamber, judges ruled that Reid had no evidence to back up his claim.

“It is now possible to get called a liar by PolitiFact for saying something true,” complained James Poniewozik and others. But True certainly would not have sufficed, here not even Half True.

Maybe the Truth-O-Meter needs an “Unsubstantiated” rating. They considered it, but decided against it, Adair told me, “because of fears that we’d end up rating many, many things ‘unsubstantiated.'”

Whereas truth is complicated, elastic, subjective… the Truth-O-Meter is simple, fixed, unambiguous. In a way, this overly simplistic device embodies the problem PolitiFact is trying to solve.

“The fundamental irony is that the same technological changes and changes in the media system that make organizations like PolitiFact and FactCheck.org possible also make their work less effective, in that we do have this highly fragmented media environment,” said Lucas Graves, who recently defended his dissertation on fact-checking at Columbia University.

So the Truth-O-Meter is the ultimate webby invention: bite-sized, viral-ready. Whether that Pants on Fire for Reid was warranted or not, 4,300 shares on Facebook is pretty good. PolitiFact is not the only fact checker in town, but the Truth-O-Meter is everywhere; the same simplicity in its rating system that opens it to so much criticism also helps it spread, tweet by tweet.

“PolitiFact exists to be cited. It exists to be quoted,” Graves said. “Every Truth-O-Meter piece packages really easily and neatly into a five-minute broadcast segment for CNN or for MSNBC.” (In fact, Adair told me, he has appeared on CNN alone at least 300 times.)

Stories get “chambered,” in PolitiFact parlance, 10-15 times a week. Adair begins by reading the ruling statement — that is, the precise phrase or claim being evaluated — aloud. Then — and this is new, post-criticism — Adair asks four questions, highlighted in bold. (“Sounds like something from Passover, but the four questions really helps get us focused,” he says.) Let’s return to the ruling we started with, from the beginning:

Adair: We are ready to rule on the Jeff Duncan item. So the ruling statement is: “83 percent of doctors have considered leaving the profession because of ObamaCare.” Lou is recommending a False. Let’s go through the questions.

Is the claim literally true?

Adair: No.

Jacobson: No, using Obamacare.

Is the claim open to interpretation? Is there another way to read the claim?

Jacobson: I don’t think so.

Adair: I don’t think so.

Does the speaker prove the claim to be true?

Adair: No. Did you get in touch with Duncan?

Jacobson: Yes, and his office declined to speak. Politely declined.

Did we check to see how we handled similar claims in the past?

Adair: Yes, we looked at the — and this didn’t actually get included in the item…

Jacobson: …The Glenn Beck item.

Adair: Was it Glenn Beck?

Jacobson: Two years ago.

Adair: I thought it was the editorial in the Financial Times or whatever. What was that?

Jacobson: Well, Beck was quoted citing a poll by Investors Business Daily.

Adair: Investors Business Daily, right.

Jacobson: We gave that a False too, I think. But similar issues, basically.

Adair: Okay. So we have checked how we handled similar things in the past. Lou is recommending a false. How do we feel about false?

Angie: I feel good.

Hollyfield: Yup.

Adair: Good. All right, not a lot of discussion on this one!

Then, after briefly considering Pants on Fire, they agree on False.

Another change in the last year has created a lot of grief for PoitiFact: Fact checkers now lean more heavily on context when politicians appear to take credit or give blame. Which brings us to Rachel Maddow’s complaint. In his 2012 State of the Union address, President Obama said:

In the last 22 months, businesses have created more than 3 million jobs. Last year, they created the most jobs since 2005.

PolitiFact rated that Half True, saying an executive can only take so much credit for job creation. But did he take credit? Would the claim have been 100 percent true if not for the speaker? Under criticism, PolitiFact revised the ruling up to Mostly True. Maddow was not satisfied:

You are a mess! You are fired! You are undermining the definition of the word “fact” in the English language by pretending to it in your name. The English language wants its word back. You are an embarrassment. You sully the reputation of anyone who cites you as an authority on “factishness,” let alone fact. You are fired.

Maddow (in addition to many, many liberals) was already mad about PolitiFact’s pick for 2011 Lie of the Year, that Republicans had voted, through the Ryan budget, to end Medicare. Of course, her criticism then was that PolitiFact was too literal.

“Forget about right or wrong,” Graves said. “There’s no right answer if you define ‘right’ as coming up with a ruling that everybody will agree with, especially when it comes to the question of interpreting things literally or taking an account out of context.” Damned if they do, damned if they don’t.

Graves, who identifies himself as falling “pretty left” on the spectrum, has observed PolitiFact twice: for a week last year and again for a three-day training session with one of PolitiFact’s state sites.

“One of the things that comes through clearest when you spend time with fact checkers…is that they have a very healthy sense that these are imperfect judgments that they’re making, but at the same time they’re going to strive to do them as fairly as possible. It’s a human endeavor. And like all human endeavors, it’s not infallible.”

The truth is that fact-checking, and fact checkers, are kinda boring. What I witnessed was fair and fastidious; methodical, not mercurial. (That includes the other three (uneventful) rulings I watched.) I could uncover no evidence of PolitiFact’s evil scheme to slander either Republicans or Democrats. Adair says he’s a registered independent. He won’t tell me which candidate he voted for last election, and he protects his staff members’ privacy in the voting booth. In Virginia, where he lives, Adair abstains from open primary elections. Revealing his own politics would “suggest a bias that I don’t think is there,” Adair says.

“In a hyper-partisan world, that information would get distorted, and it would obscure the reality, which is that I think political journalists do a good job of leaving their personal beliefs at home and doing impartial journalism,” he says.

Does all of this effort make a dent in the net truth of the universe? Is moving from he-said-she-said to some form of judgment, simplified as it may be, “working?” Last month, David Brooks wrote:

A few years ago, newspapers and nonprofits set up fact-checking squads, rating campaign statements with Pinocchios and such. The hope was that if nonpartisan outfits exposed campaign deception, the campaigns would be too ashamed to lie so much.

This hope was naive. As John Dickerson of Slate has said, the campaigns want the Pinocchios. They want to show how tough they are.

“I don’t think we were naive. I’ve always said anyone who imagines we can change the behavior of candidates is bound to be disappointed,” said Brooks Jackson, director of FactCheck.org. He was a pioneer of modern political fact-checking for CNN in the 1990s. “I suspect it is a fact that the junior woodchucks on the campaign staffs have now perversely come to value our criticism as some sort of merit badge, as though lying is a virtue, and a recognized lie is a bigger virtue.”

Rarely is there is a high political cost to lying. All the explainers in the world couldn’t completely blunt the impact of the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth’s campaign to denigrate John Kerry’s military service. More recently, in July, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee claimed Chinese prostitution money helped finance the campaign of a Republican Congressman in Ohio. PolitiFact rated it Pants on Fire.

That didn’t stop the DCCC from rolling out identical claims in Wisconsin and Tennessee. The DCCC eventually apologized. But which made more of an impression on voters, the original lie or the eventual apology from an amorphous nationwide organization?

Brendan Nyhan, a political science professor at Dartmouth College, has done a lot of research on the effects of fact-checking on the public. As he wrote for CJR:

It is true that corrective information may not change readers’ minds. My research with Georgia State’s Jason Reifler finds that corrections frequently fail to reduce misperceptions among the most vulnerable ideological group and can even make them worse (PDF). Other research has reached similarly discouraging conclusions — at this point, we know much more about what journalists should not do than how they can respond effectively to false statements (PDF).

If the objective of fact-checking is to get politicians to stop lying, then no, fact-checking is not working. “My goal is not to get politicians to stop lying,” is another of Adair’s refrains. “Our goal is…to give people the information they need to make decisions.”

Unlike The Washington Post’s Glenn Kessler, who awards Pinocchios for lies, or PolitiFact, which rates claims on a Truth-O-Meter, Jackson’s FactCheck.org doesn’t reduce its findings to a simple measurement. “I think you are telling people we can tell the difference between something that is 45 percent true and 57 percent true — and some negative number,” he said, referring to Pants on Fire. “There isn’t any scientific objective way to measure the degree of mendacity to any particular statement.”

“I think it’s fascinating that they chose to call it a Truth-O-Meter instead of a Truth Meter,” Graves said. Truth-O-Meter sounds like a kitchen gadget, or a toy. “That ‘O’ is sort of acknowledging that this is a human endeavor. There’s no such thing as a machine for perfectly and accurately making judgments of truth.”

Update: This story was edited after publication to clarify details of the “Star Chamber” process. Political cartoon by Chip Bok used with permission.