![]() We all know that The New York Times and other papers have been thinking hard about finding ways to charge readers for the news on their web sites, and there’s evidence that the decision-making process is moving along. Bloomberg has reported that a survey of print subscribers included this sentence:

We all know that The New York Times and other papers have been thinking hard about finding ways to charge readers for the news on their web sites, and there’s evidence that the decision-making process is moving along. Bloomberg has reported that a survey of print subscribers included this sentence:

The New York Times website, nytimes.com, is considering charging a monthly fee of $5.00 to access its content, including all its articles, blogs and multimedia.

It also asked about a $2.50-a-month “discounted fee” for print subscribers.

What bugs me most about that survey isn’t the idea that the Times wants to charge for its web site. As a news consumer, I love having the world’s newspapers free and a click away. But I know enough about the financial situations of most American newspapers — and the desperation they feel about their tumbling revenue numbers — that I’ve come to accept that we’re going to see a lot more experimentation with charging for access in the coming months. I wouldn’t be shocked if the majority of major American newspapers erected some sort of pay wall by year’s end.

No, what bugs me most is that the Times is thinking about charging so little.

The Times is the premier brand in American journalism, and it appeals to an elite audience. Charging anything for access to a newspaper web site is going to drive away a lot of readers. But if you’re going to charge and go through the massive dislocation of turning something free into something with a price tag — charging just $5 makes it seem like a damaged item in the discount bin. Here are three arguments for why the Times — if it’s going to charge — should charge more:

— Five bucks a month doesn’t generate enough revenue to make a dent in the paper’s problems. Hamilton Nolan at Gawker notes approvingly that “if all 650,000 print subscribers paid $5 a month for the website, that would be an instant $39 million per year.” That’s likely very optimistic, since the Times is talking about half-off for print subscribers — and, of course, a hefty portion of Times print subscribers are plenty happy with a print-only lifestyle. But let’s say half of print subscribers sign up at $2.50 a month. That’s $19.5 million a year.

How about online-only readers? The Times Select experiment topped out at a little over 200,000 subscribers and $10 million in annual revenue; that was at $50 a year and covered only a small fraction of the Times’ content. Let’s imagine the number of non-subscribers willing to pay is now three times what it used to be. At $5 a month, that’s $36 million.

This is obviously back-of-the-envelope stuff — and I suspect it’s an optimistic envelope — but that’s about $55 million a year. The New York Times Media Group (which also includes the International Herald Tribune) had revenue of $396 million in the first quarter. In other words, this probably optimistic estimate would bump up revenues by about 3.5 percent. And that’s before you factor in the inevitable loss of online advertising revenue, no matter how semi-permeable the pay wall ends up being.

At a time when advertising revenues are cratering — and nytimes.com is the single strongest untapped asset the newspaper has — to go through all the dislocation of a pay wall for only a tiny bump in revenue doesn’t seem worth it.

— It ignores the lessons of micropayments. There’s been plenty of debate over Chris Anderson’s Free, but one of his strongest arguments is that there’s a huge mental gap between something that’s free and something that costs even a tiny amount. The mental transaction cost of paying for something when free options are available is very real. But the flip side of that is that the fear newspaper execs have about charging for their web sites should be primarily about the act of charging — not about the specific price point.

The Times is well aware that mental transaction costs are a big hurdle; that’s why they’re down on micropayments as a solution. As Scott Heekin-Canedy, New York Times Media Group president/GM, said recently:

Our general view is that micropayments are too cumbersome. It is just like getting in a taxi and the meter is running for every word or page you consume. It creates an anxiety that just doesn’t belong here.

Anderson writes about a Dan Ariely experiment in which people are faced with the choice of “buying” a 14-cent chocolate truffle or a free Hershey’s Kiss. Sixty-nine percent chose the free Kiss. When the prices were hiked a penny — 15 cents for the truffle and 1 cent for the formerly free Kiss — 73 percent chose the truffle. (Some folks disagree about the specific numbers.)

One lesson to draw from this is that free is a very attractive price, and that charging anything above zero will drive away a lot of customers. And that will no doubt happen if the Times puts all its news behind a pay wall.

But the other lesson is that, once you get past that zero barrier, you have more flexibility with pricing. Raising the price of a truffle from 14 to 15 cents didn’t drive everyone away.

Or to look at it another way: If someone is willing to pay $5 a month for the Times, wouldn’t they probably also be willing to pay $6? Or $7? There are probably some people for whom there really is a magical cut off at $5.75 or whatever. But I’d wager the vast majority of people who are willing to pay $5 would also be willing to pay $10. And a big chunk would be willing to pay $15. The big hurdle is from free to non-free, getting people to actually turn over their credit cards and commit to paying anything. Once you’re past that, setting too low a price is leaving money on the table.

— It sets an implicit ceiling on what other newspapers can charge. Say you’re an exec at The Seattle Times, or The Kansas City Star, or my old paper, The Dallas Morning News. You’re bleeding heavily; your newsroom is maybe half what it used to be, and the numbers aren’t getting any better. You’re thinking about how you can get away with charging for your web site to generate some revenue.

Then you hear that the Times — the gold standard of American newspapers — thinks its web site is worth about $5 (or $2.50) a month. How much pricing room does that leave you? Once that becomes the top of the market, what are you stuck with — three bucks a month?

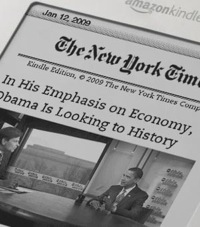

We already have a marketplace for digital news to compare this to. On the Kindle, the Times costs $13.99 a month, but regional papers

We already have a marketplace for digital news to compare this to. On the Kindle, the Times costs $13.99 a month, but regional papers price themselves are priced at somewhat less ($9.99 for the Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Arizona Republic) or a lot less ($5.99 for the Seattle Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Houston Chronicle). If that gap in prices carries over at all into how newspaper value their web sites, everyone who’s not the Times (or the Wall Street Journal and maybe Washington Post or Los Angeles Times) is going to be stuck in the bargain bin before they even start charging. (Update: Someone pointed out to me that Amazon sets Kindle subscription pricing, not newspapers — my apologies. But if anything, I think that strengthens the argument, since Amazon has the richest data across publishers of what digital subscribers will stand for and is presumably trying to maximize its revenues.)

(Kindle pricing also forces the question: If Times stories without video, without interactivity, without color — and without all the other stuff at nytimes.com — are worth $14 a month on the Kindle, why in the world is the web site only worth $5?)

What price would I set for nytimes.com? There are plenty of smart business people at the Times, and they have access to a lot more data (like those survey results) than I do. But I think charging anything less than $10 a month devalues the product and doesn’t maximize revenue.