It’s a tablet experiment in cross-pollination. How do you use the 48 square inches of an iPad to expose the depth of public radio — thousands of hours of national programming, local shows, and community news that add up to a window on the world?

In southern California, KPCC’s new iPad app is a shape-shifting kind of product, heralding a new local promise — and offering an insight into what a greater shared local/national public radio experience may look like. All the metaphors in the product may not perfectly jell — it is a newly released V1 product — but its ambitions are great.

It is only the second local public radio iPad-specific news app in the market (Minnesota Public Radio’s launched earlier this year) and acts on the realization that more than half of public radio’s digital traffic will likely be mobile by 2015. Indeed, in a world where radio is still valued but a radio is becoming an anachronism, the new app acts on our near-compulsion to toggle.

What strikes me about the KPCC app is its largely successful attempt to bridge different elements that could otherwise be in tension with one another.

First and most importantly, it’s local news and it’s radio programs — a balance many public radio sites find hard to strike.

On the news side, it’s both locally curated twice daily and it’s a stream of news. It’s local news and it’s national news. It’s text news and video news and audio news.

On the radio/programming side, it’s radio and it’s audio. It’s livestreaming and it’s on-demand programming. It’s whole programs and it’s segments of programs.

It’s an exercise in toggling. We’re well beyond the old binary controls of balance, bass and treble. It’s a consumer movement across content types and brands: Media can no longer choreograph it — they can only provide a suitable stage.

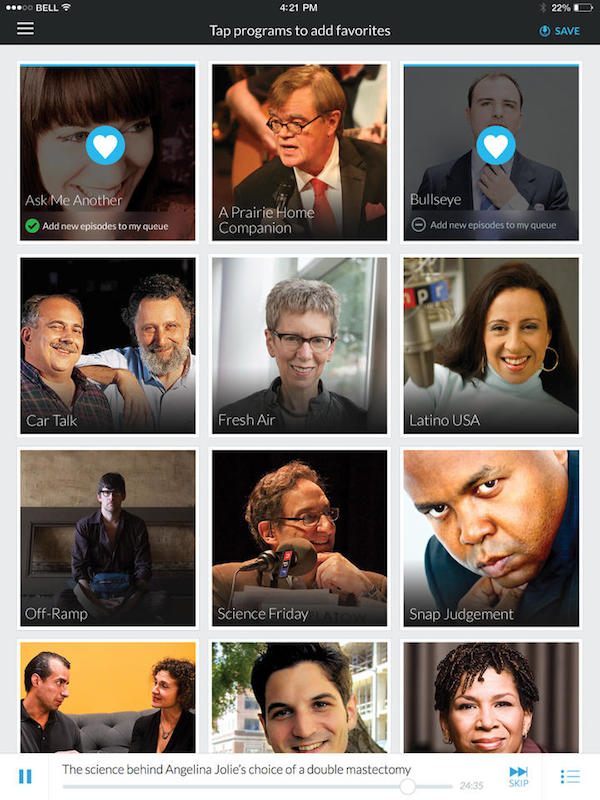

The bridges here are important because of all that complexity. Just as important is the role of personality. It’s inarguable that we take in the human news voice differently than we do the written word. Public radio leverages this personality — resulting in a mass medium that has grown in usage and reach markedly over the last decade — and does it uniquely. There are lots of public radio apps, but almost all of them rely on words to stand for a program. The KPCC’s “All Programs” page is a set of photos of program hosts, from Fresh Air’s Terri Gross to Marketplace’s Kai Ryssdal to KPCC’s Larry Mantle. Touch the picture, and you get to current and most recent episodes. Want to use the app as a “radio”? Just edit your favorites and then new shows are automatically added to your queue.

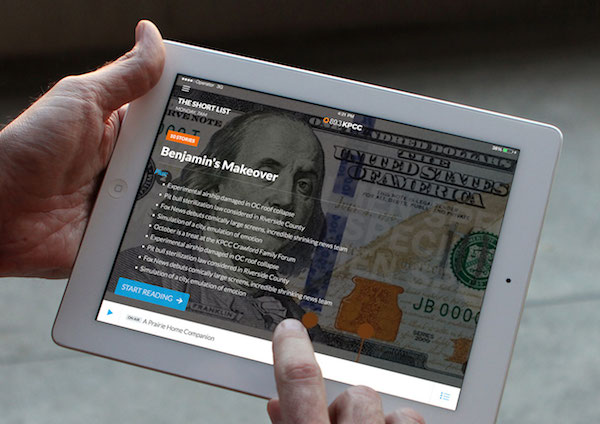

The central idea of the design: Make it easy for readers to move back and forth between and among these various content types. That means a live listening bar available on the bottom of each page, and a number of ways to get back to news or a program with a single tap. KPCC’s Alex Schaffert is a digital veteran, having spent eight years at the station, and as director of digital media headed up the project. The effort is funded with a $1 million, two-year grant from the L.A.-based Keck Foundation, paying for some outside conceptual design help and five full-time positions. Schaffert emphasizes that given the fundamental shift in the business to mobile, developing internal expertise is now a given.

“The KPCC iPad app was entirely built in-house,” she says. “Many news organizations outsource app development, but I think we’ve reached a critical juncture where the user experience, the design, and presentation of news are just as important for a winning product as the content itself. App development shouldn’t be an afterthought, delegated to a vendor. The presentation of news in the mobile space is core to our business today, and in my opinion it’s vital that news organizations build that expertise among their ranks. You need programmers working side-by-side with product people and content producers in order to arrive at an innovative product.”

Like most big public radio stations, KPCC has seen explosive mobile growth, with mobile now at about 35 percent of digital traffic. Its smartphone app has been useful, but the station wanted to seize the platform of the day, the tablet, and use it as a base for KPCC’s large local news ambitions (“The newsonomics of the death and life of California news”). Those ambitions have grown, as former L.A. Times editor Russ Stanton and former Sacramento Bee editor Melanie Sill were hired as VP/content and executive editor, respectively. The news staff will number 100 by the middle of next year, as the print landscape in the Southland swirls with post-bankruptcy intrigue, consolidation, and more news capacity shrinkage than expansion.

In looking at data, KPCC found that its audience is even more iPad-centric than the population overall. It’s a strong two-year trend line; even with KPCC’s smartphone apps, iOS downloads outdistance Android nine-to-one. In addition, there isn’t much overlap between radio listenership and digital use at public radio stations nationwide. Fewer than 20 percent of listeners regularly use a local station’s website or mobile app; fewer than 20 percent of its app or website users listen much to its radio offerings.

That understanding opened up design as a green field to attract new audiences.

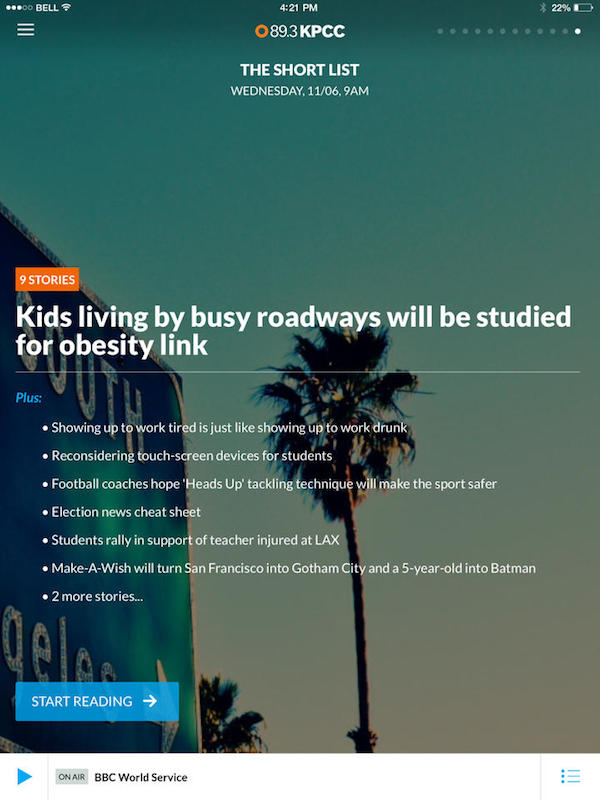

Behind the design are those five staffers. One manages the product, two are developers and the other two produce the app’s centerpiece, The Short List, a highly visual feature. “It’s a need-to-know product,” says Schaffert, interestingly using the same words New York Times CEO Mark Thompson uses to describe one of his planned new paid digital products. The idea: 10 stories, picked early in the morning for the peak 8-9 a.m. mobile reading hour and then again in time for the 4-5 p.m. surge. They are drawn from local (KPCC) and national (NPR and AP) reporting, from big global news (“India’s Supreme Court upholds anti-gay sex law”) to the occasional large reptile story (“Did the dinosaur asteroid send life-bearing rocks to Mars?”).

We toss around words like multi-platform, multi-device, multi-screen, and “news everywhere” to describe the countless choices consumers have. From a publishing point of view, though, these choices have created headaches, posing tech and cost challenges — even before we get to the over-thought existential ones.

As a radio station, KPCC is grappling with the same existential issues as other legacy media trying to break beyond their legacy platforms. With Rebecca Howard’s new charge at the New York Times, we see the same effort, as we do in Cincinnati (“The newsonomics of Scripps’ TV paywall and the Last Man Standing Theory of local media”) and many other markets, as local TV stations go digital and text. How do you show both who you are and who you aspire to be? The solution: Put aside vain attempts at self-identification (and self-esteem) and imagine yourself behind the customer’s eyes and ears. That’s what the BuzzFeeds, Circas, Der Correspondents, and all the other digital startups do. The world provides us with a simple truth: We consumers have proven to care little about Old World definitional differences. We simply like what works.

Where might this product go? If it’s static, readers may write it off as a good start, but one not satisfying enough for the deep-reading public news audience. If it develops, though, in breadth, depth, and navigation, it could offer up new ways to deepen relationships with members (who contribute 53 percent of the station’s revenues; full station report here) and introduce new customers to public media.

Further, KPCC’s new platform, along with other recent innovators — including New York’s WNYC, which recently produced a state-of-the-art audio-centric smartphone app — could well take advantage of a long-in-discussion wider public media network experience. Despite all the change at the top at NPR (seven “permanent” or temp CEOs in six years), NPR has continued its talk with top public radio stations in major markets around the idea of what once was called “Pandora for public radio,” as a number of top public radio execs have shared. That idea is as “simple” as KPCC trying to make consumer simplicity out of its welter of radio/audio/text offerings. In fact, the national complexity is far greater, given the multiplicity of news staffs, personalities, technologies and market strategies found around the public radio country. Those are just the organizational questions; how these products will generate substantial revenues is still to be determined. Though the national NPR is fundamentally different than the regional KQEDs, WBURs, OPBs and WBEZs, it’s a meaningful difference that isn’t meaningful to consumers. Add in public radio power centers like CPB, APM, PRI, PRX, and other funders, creators and producers of programming, and the ability to balance priorities, revenue streams and traffic flow can seem practically Rubik’s Cube-like.

Still, expect NPR to get to a harmonic convergence far sooner than later. Already, much smart work has been done at mastering the content management to allow greater sharing and use of content among public radio stations and NPR. Now it is the business issues that must be finally wrestled to the ground, as national/local relationships inevitably must twist and turn in the next mobile age. If all that messy sausage-making can be resolved, then public media could do on a national/local level what KPCC is starting out to do in L.A.: Make it finger-simple to move in and play among the bounty of public media content floating through the country on any given day in words, voices, music, pictures, video — and the personalities animating them.

For public media, it’s not just a question of upside, though there’s plenty of that which increased engagement can generate in dollars. In every news and entertainment medium, it is the aggregators — the Googles, Facebooks, Netflixes, iTunes, Hulus, Spotifys, Pandoras and Flipboards — that show the greatest growth. (And in each of those industries, we’ve seen fierce controversies about publisher/creator role in aggregation, controversies that usually last long enough for the incumbents to forever lose their standing.) Against that landscape, public media still possesses the ability to pull itself together. At the same time, there’s a deepening appreciation that if it doesn’t pull itself together soon (and even if it does) the TuneIns, iHeartRadios and Stitchers may well succeed in creating audio aggregations to beat all other audio aggregations.

For public radio, smart, teamed curation with the consumer utmost in mind is only the first step in meeting that emerging competition, and deciding where to compete and where to partner.