Editor’s note: Nieman Lab friend and contributor Nikki Usher is out with a remarkable new book, Making News at The New York Times. It’s the result of five months she spent immersed in the Times’ newsroom in early 2010, observing newsroom culture, watching how news turned into stories, and seeing how new norms of digital journalism were established inside America’s premier news organization. (You can read the book online.)

Our own Joseph Lichterman has a Q&A with Nikki, but we also wanted to give you a taste of her findings. Here’s an excerpt from Chapter 3, “The Irony of Immediacy,” which focuses on how perhaps the most watched space in digital journalism — the homepage of NYTimes.com — gets assembled.

One final note: Remember, this is a snapshot from 2010 — a long time ago in web time. People really like to talk about the Times, so I’ll just note that, while elements of any company’s culture persist over time, what Nikki observed then shouldn’t be taken as a perfect reflection of the Times in 2014.

Online newswork departed from the regularly scheduled process of decision making, planning, and editing a story that dominates print production. In fact, it operated according to an entirely different rhythm. Production for the web was a frenetic activity, often with little clear strategy about how, when, and why stories should be posted. Online news production was largely a response to the perceived pressure of immediacy, defined as ASAP, constant updates for online journalism — and in parallel, immediacy emerged as a value that structured and ordered newswork and gave journalists a particular vision of their role as professionals.

Yet journalists did not speak directly about “immediacy.” Editors could not explain to me why they thought stories should be updated as quickly as new information was available, and web producers could not explain to me why they believed there was a need to keep the pages constantly updated, or looking “fresh.” “Fresh” was a quality that web producers and others charged with online journalism associated with their presumed sense of what the audience wanted: something new, something different. But just like “feel” or “news sense,” “fresh” depended on a journalist’s (most often a web editor or web producer’s) individual judgment, honed from the time they’d spent thinking about web production. Determining what is “fresh” is one way to explain how journalists tried to make sense of the constant presence of a never-ending deadline in the digital age.

“Fresh” was also one way for journalists to deal with the fact that they had no control over when audiences might be clicking on web content. However, they did know that, at least at the Times, there were always thousands of people looking at the web page at any given time. The goal was to keep them coming back. The understanding from journalists working on the web was that fresh content was better. Updated content brought in new readers or kept readers coming back, so the homepage could not be static, or at least not for very long. The morning newspaper delivered to your home (if you got one) should look nothing like the homepage you opened at work in the morning.

What the homepage editor did during the day, when most people were getting their news online, was relatively unstructured. While the homepage editor had some sense of when he would add new stories to the page, there were no conversations between him and the managing editors or executive editors, for example, about which stories should remain in place during the day. Instead, it was up to the day’s homepage editor and the continuous news editor, Pat Lyons, to make these decisions.

I asked associate managing editor Jim Roberts why there were no formal web meetings like the print meetings to decide coverage and story placement. He told me, “You’ve seen how fast the web moves. You can’t sit around and plan for that. It’s too quick for people to stand around and debate.” This comment was a clear recognition that the print process couldn’t work for the web. There were some meetings that lasted no more than 10 or 15 minutes, and they didn’t offer much guidance about which stories should lead the homepage and when. The morning web meeting was an opportunity for journalists to tell other staff what stories might be coming down the pipeline, but the homepage editor I followed over the course of one morning, Mick Sussman, said he rarely paid attention to this meeting. In fact, he admitted that he couldn’t hear it from his desk. Decisions as to what column of the web page to put a story in, or how to order the stories, or how long to keep a story in place, were the kinds of things left up to the homepage editor and his or her supervisor, not decisions made by committee — particularly during the day, when most people in the United States come to the site.

And in the evening, there were two “handoff” meetings to make web producers from around the newsroom aware of content from across other sections and to inform the night homepage editor. But there was no debate over homepage play, no extended discussion over what stories merited the most attention, and very little conversation about the stories themselves — just reading down a list of what stories were available. In this sense, consider that an editor for print could spend his or her day in meetings talking about story placement, while on the web, there were virtually no meetings that offered the same kind of opportunities.

Instead, in looking at the online rhythms of web production on NYTimes.com, the picture that emerges is not one that involves many actors, but instead focuses on the activities of a single individual. Thus, in looking at the homepage editors and the online business editor, we get a sense of the rhythm of each page, a rhythm that is articulated through the vantage point of one person. This is distinct from what we saw in the print rhythms, where the portrait of newswork is an extensive detailing of collaborative discussions. The close-ups of individual web editors/producers, though, underscore the imperative of immediacy that faced the online newsroom.

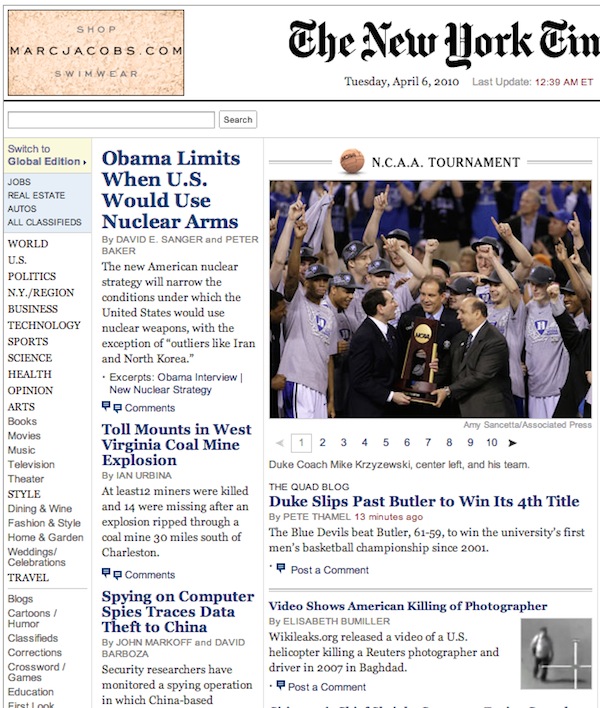

On April 2, 2010, I spent the day with Mick Sussman, one of the morning homepage producers for the U.S. edition. His shift was from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. He explained to me that his goal was to have something new up on the homepage about every 10 minutes (keeping the page looking “fresh”). The big changes that he made were in the “A” column, or the leftmost column going down the homepage; the photo spot, which he tried to change every 30 minutes; and the “B” column, or the column underneath the photo spot, which was a prime spot for a news story other than the top of the “A” column. Sussman was also constantly rotating out blogs in the “on the blogs” section, but he admitted, for instance, that he didn’t have much knowledge about style or sports, so he often relied upon other people to alert him when something was important.

Sussman had to write headlines for nearly all the stories he put up on the homepage, though Pat Lyons, the continuing news editor who, in theory, supervised him, would offer suggestions, as would other editors and web producers via IM. Sussman also often had to write the web summaries for the stories (the short blurbs under the headlines), though he relied on what came from copy editors or the web editors. But the nuances of the web page itself often demanded that he do the last-minute editing of these summaries before they went in front of millions of NYTimes.com readers, often going up without any kind of editorial oversight other than his own news judgment and copyediting skills. Lyons would provide feedback if something needed to be tweaked, but this was a publish-first mentality. As I watched Sussman work, I noticed how much hand coding and manipulation of the website he had to do: his job involved not only journalistic judgment but also considerable web skills.

When a new story popped up in his queue, usually over IM, Sussman would send a headline to Lyons, also over IM. If Lyons didn’t respond, Sussman would just put up a headline. When I was observing Sussman, he asked Lyons about putting up a story on a conspiracy movie. When Lyons didn’t respond, Sussman put the story up. His justification was, “I think this is pretty interesting,” and he noted that he always liked conspiracy stories. For about half an hour, this story was in the section right underneath the main photo on the homepage — a prominent spot. This is an indication of the latitude that Sussman had over the page, shaping it to his own interests. A few minutes later, the foreign desk alerted him to a story on Saudi Arabia, and Sussman decided to put this story on the homepage. While these stories often went through layers of debate and discussion at each individual desk, their quality depended on this editorial judgment. A breaking story, for example, might be headed to Sussman without quality checks. To some degree, Sussman depended on the quality of work provided to him. However, Sussman was ultimately in control of who saw what story, and for how long, on the web.

Sussman explained that his goal was to balance the homepage content so it was distributed evenly among all of the different sections of the newspaper (a goal echoed by other homepage editors). His other, perhaps most important duty was to keep the news constantly updated in order to make sure that NYTimes.com had both the latest content and new content, so people would have reason to keep coming back to the page. “In six hours, there should be a complete turnover of the page,” he noted. “There is an imperative to keep the page looking fresh for readers, so I am constantly tinkering with it, looking at blogs, reading subpages, and seeing if there is other content to pull up for the page.”

When I watched him, he spent most of his morning preparing for the jobs-numbers story. First, he had to prepare an alert, and then he had to deal with constant changes to the headline for this particular month’s story (the April 2010 numbers). Sussman also checked to make sure that the Times hadn’t missed anything by watching the wires when he had a chance.

Noon EST was a big time for updates to the homepage, as many people would check the web during their lunch break. Sussman put entirely fresh content on the homepage, such as a story about attacks in Israel and a Times feature story on Senator Kirsten Gillibrand.

On his own, Sussman learned that President Obama was speaking at noon, and decided to make sure he had a video link on the homepage so the president could be featured. Sussman made three other major updates to the B column while I watched him.

Each major update consisted of changing the big picture on the homepage. The course of the afternoon went as follows: At 1 p.m. Sussman’s first update was to put in TimesCast, the five-minute Times video that included (at the time) some highlights of the Page One meeting and interviews with reporters about breaking news. At 2 p.m., he put a photo of President Obama speaking in the main picture space. He then inserted international news into the second slot, underneath the jobs report. Then, by 3 p.m., he had made another major switch, moving news about New Jersey governor Chris Christie into the column beneath the main photo. All of these changes seemed a bit superficial — but they each made the homepage look completely different.

None of the other editors was consulted when Sussman made these changes. To be even more clear: one person was writing the web headlines, as well as the copy that went underneath these headlines. One person for millions of potential readers. And there was no copy editor for these web headlines.

While other people in the newsroom IMed Sussman with suggestions for web summaries and headlines, only he knew exactly what would fit together on the homepage. And ironically, most of the time, he was only giving a very quick read to any of these stories, if he read them at all. His attention was focused on the lead of the story, the headline given by the desk, and the guidance of other web producers. As far as I could tell, he wasn’t making any errors, but the entire process seemed like it could leave the homepage vulnerable to mistakes. Yet the system did seem to work. Only rarely did anyone in the newsroom complain that a web summary did not represent a news story — and of course, that could quickly be changed.

Sussman had figured out a routine to keep the Times’ homepage constantly looking different. Roughly, the rules went something like this: He would put up a new blog post every 10 minutes, which he culled from his RSS feed. Some repositioning of stories took place every 20 to 30 minutes. New stories were added as they came up, if they seemed to meet Sussman’s internal criteria of newsworthiness. A major, visible change to the homepage was made every hour. Sussman checked the competition three times on the day I shadowed him (CNN, BBC, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal) but only once mentioned a competitor’s story to Lyons. Rather, he was preoccupied with updating the homepage with Times content and wasn’t paying much attention to anything else.

He barely had time to run up to the cafeteria during the day, and he made sure to do so at about 11:20 in order to be ready for the big noon push. Sussman had tried to make the continual rotation of stories more predictable and routine, but it depended on everyone else in the newsroom feeding him a continuous supply. At a place like The New York Times, with over one thousand people in one building, as well as the International Herald Tribune staff in Hong Kong and Paris, keeping updated original content on the homepage was quite possible, during the New York news day at least. Nighttime presented different challenges, as we will see next. But for the day homepage editor, immediacy, with some undefined sense of “freshness,” ultimately influenced almost everything, from when Sussman ate to his near-continuous workday spent changing and updating content on NYTimes.com.

Ironically, while the immediacy of trying to keep the page updated seems to reign during the day, night production of the homepage online relies on cues from the print paper. In this odd way, the two newsrooms converge. The night homepage editor was still concerned with keeping the web page “fresh,” but she had also been instructed to use the guidance of the front page and section editors when selecting news stories for the homepage. And the locus of production of most of the news, the New York bureau, shuts down for paper deadlines in the evening, so the amount of brand-new news that can be placed on the website slows to a trickle.

The night I observed Lillie Dremeaux, April 5, 2010, was also the night of the worst mine disaster in American history. Thus, I got to witness Dremeaux in an on-demand, breaking-news environment, where her web summaries would be the latest anyone coming to NYTimes.com would know about the disaster if they happened to just want a quick headline. Each subsequent web summary that night changed as more details of the story became clear. Thus, Dremeaux’s job took on added importance. She was not just refreshing the homepage to keep things looking interesting; she was also refreshing the homepage with the breaking news coming out of the disaster.

At first glance, her routine was much the same as Sussman’s. She was in constant communication with night editor Gerry Mullany about when new copy would be available from the copy desk, as by this time of the night, most breaking stories were now in their final form, and feature stories set for the print paper were being prepared for the print deadline. Like Sussman, she was continually bombarded by IMs from other web producers with requests to get their desks’ content on the homepage. She also seemed to be making constant changes to the page, and she kept only a minor eye on the competition — with this research never affecting what stories she chose to put where — though she did make a note in an email of which competitors she checked.

Dremeaux paid attention to one of the two night web meetings, the 7 p.m. meeting, where web producers informed each other and Mullany of what content was available. This meeting was to help Dremeaux know what the big stories for the day had been, and each web producer from each desk had the chance to pitch his or her big stories for homepage play. In addition, as the night homepage producer, Dremeaux was also guided by the decisions made by print editors. But it would be up to Dremeaux to decide when, where, and for how long material would appear on the homepage. Her goal was to give each section’s strongest dress page story (or printed section story) play on the front page for at least some period of time.

Over the course of the night, the homepage became increasingly static and began to look more and more like the print paper. Around 9 p.m., Dremeaux printed out a mockup used to guide the print Page One designers that showed where each story on Page One would go. This mockup guided where she placed each story. Using the visual cues about the most important story in the paper (the lead story in the righthand column) and the off-lead (in the left-hand column), she would place these pieces in the most prominent places on the website (the A column or under the B column). She would also be sure to have the other stories that made Page One in prominent places. As Dremeaux put it:

The front page tells me what are the five or six most important stories of the day. I follow that because there are some really important editors — the most important editors at the Times — saying that this is what we think is important. And the homepage should reflect that.

Strangely enough, the homepage late in the evening was most like the paper people would see in the morning. In fact, the individual section pages were remotely copy edited — by a university professor. Web producers could not go home until they had gotten their “Cowling note,” a brief email that alerted them to capitalization issues, spelling problems, and so on. As web producer Cate Doty noted, “The website is most edited when no one is looking at it.”

Dremeaux had an added constraint that Sussman did not — she had to make sure that there was enough new content to keep the homepage looking “fresh” in the morning. Since the homepage had already run through many stories throughout the day, Dremeaux had to be careful to save some of the major stories of the evening (which would be in the print paper the next day) for the morning.

This way, the following morning, when no new news of major significance to U.S. readers had yet occurred, and very few U.S. reporters were on duty, there would still be new content for the page. Thus, the need to keep things “fresh” by keeping the website looking new can be seen as a recent constraint on newswork in the sense that it might shelve news for a little while. In such a case, keeping things fresh may actually make them, like day-old bread, a little bit stale. Immediacy imposes a driven focus for new content on journalists and the web page, but when there isn’t any (or enough) new content, the website tried to balance the desire to keep the homepage looking ASAP with the reality that journalism is not, in the end, ASAP at the Times, at least most of the time.

Still, by the time most people woke up, the homepage would look completely different from Dremeaux’s carefully matched headlines and the carefully edited section pages, with the news that had come in from the foreign desk and the business desk heading the site, and the homepage producer cycling in the remainder of the material that hadn’t made the homepage the night before. As Doty put it:

The interesting thing is that when I wake up at 10:30 the whole website is different. So the website is totally edited when no one is watching. The page will look completely different from now [12 a.m.] to the morning so that’s kind of a fascinating thing to note.

Thus, the life of the homepage producer revealed some particularly important online imperatives and values at the Times. There was considerable importance placed on keeping the web page looking as fresh as possible, particularly throughout the workday. The homepage producer employed the breadth of content available throughout the Times to make this possible. What Sussman and Dremeaux did each day didn’t vary much, and both had their own routines. However, what stories to place where, in the end, was up to them, with perhaps limited supervision from their editors. Writing the web summaries and the headlines fell down to one or two pairs of eyes, at most, versus the multiple rounds of copy edits for a news article. The homepage producers had considerably more latitude and less oversight than anyone working on the print side of the newspaper, and for the most part, they were making decisions about which stories were most important based on what news happened to be available at each particular moment.

Most days when I was doing my research, I would get into the newsroom in the morning and prop myself up comfortably in a chair next to Mark Getzfred, the online editor for the business section, before heading off to do any other research. Some highlights from his work days, which began when he took the train at 6 a.m. from his home in Connecticut and read on his BlackBerry and Kindle until he arrived in New York by 7:30 a.m. or so, then ran to at least 5:30 or 6 p.m., show how the business desk attempted to fill the need for online content. Like Sussman, Getzfred took to his job with intensity, underscoring the obsession with the new and what was now online.

Getzfred began his day trying to find fresh stories for the business web page and the business global page (the main business pages) that had not been in the business section the night before. He started by searching through International Herald Tribune content that had come in from the night before; the business desk relied on the content from the partnership with this paper owned by The New York Times Co. to help fill the morning edition.

So, for instance, on January 12, 2010, he spent his morning (as he did most mornings) reframing a story from the Asia bureau of the International Herald Tribune on Japan Airlines’ struggles with bankruptcy, just to get something new on the page. He followed this up with a story on Airbus, the European airline manufacturer, another story that had come from the IHT. Both stories went up (though in different places) on each of the business pages.

He would constantly scan the wires, and he would begin rewriting a markets story even before the U.S. markets opened. An Asia-based writer would have left off this story in the very early hours of the U.S. morning, it would have been picked up by the European markets writer in the Paris bureau of the IHT by early morning U.S. time, and then Getzfred would begin filling in the details about premarket trading in the United States, gleaning content from the wires. He noted that this was one of the most popular stories on the site — “people like reading about markets and we give it a little context” (again emphasizing how the Times hoped it was providing value-added content). Around 9:45 a.m., he stopped for a brief 15-minute meeting to discuss what was going to be available on the website with the other web editors. This was the meeting that Sussman said he couldn’t hear — despite the fact that this was one of the few moments when web editors got together to talk about stories. Notably, this meeting only described what was available and the importance of these stories at a particular moment.

He would then rush back downstairs and continue to rearrange the business pages. He explained to me on March 1, 2010, his sense of the pressure that he felt on the web: “There is some pressure, but it’s not like we are 24-hour news with always something to fill. But there is some pressure.” And then he began filling the business pages with a series of stories that would generally be trivial by the end of the day, either inside the print paper or not even present at all, such as any story about economic indicators, hearings, or reports. A typical story from that day was one he took from the wires about the fact that personal spending was up at the expense of the personal savings rate. Another was still more about the ongoing Toyota brake failures. He explained: “Akio Toyoda apologized again…[It] probably won’t go in the paper.”

Getzfred told me later that these stories were nonetheless likely to make the homepage, as “the homepage, particularly in the morning, is always looking for news. They want something fresh they can put up there.” While Getzfred declined to say he was working at an immediate pace, he rarely took breaks, even for lunch. His focus was, indeed, on keeping the web page looking new, in part because Times readers, as he put it, “wanted to see something else,” and “we have to respond to what is changing throughout the day.”

On that March morning, he IMed Lyons, the editor who worked closely with Sussman, to alert him that a Federal Reserve Board member would be retiring. His IM said something to the effect of “Donald Kohn is retiring,” to which Lyons replied, “Who is that?” Getzfred explained, and Lyons IMed back to note that they didn’t have much, so it would go on the homepage — even though Lyons didn’t have any idea who Kohn was. The homepage in the morning and the business page in the morning were both hungry for news, even news that wasn’t of much substance, as long as it could be cycled into the spots for readers with news from the day, rather than news from yesterday.

Getzfred continued most of his day filling content as he could with wire stories and updates from reporters and keeping the markets story up to date. He would shuffle around stories and put in new Times content when he had it, but most of the time, new substantive stories from the business desk, the kind talked about in the news meetings, weren’t ready during the day. So as a result, the business page during the day was a mix of blog posts being pushed out by the six or so major blogs and small chunks of news — unless there was something major brewing.

Getzfred spent his day hunched over the computer, constantly scanning stories, rewriting AP content, making sure that his markets reporter was staying on task, and keeping the business web page filled with new content as soon as he had some. Notably, this was not even always “good” content, content that would even be talked about in Times news meetings; it was just new. Stories about corn subsidies, for example, might be leading the page for a good part of the morning — until 10 or 11, when some better content might be flowing in from more substantial Times news. In most cases, there was likely only one story that could really feed the business page with original, print-discussion-worthy content until later in the afternoon or evening.

Getzfred was also the first line of defense for making sure that breaking news got on the website as fast as possible. On January 12, 2010, that meant making sure the Times had two fairly important updates. The first came around 5 p.m., when the Times’ media writer Bill Carter got a scoop that Conan O’Brien would refuse to be The Tonight Show host if Jay Leno was moved back to his old 11:35 p.m. slot. At the time, this was big news: The Times was the first news organization to have news about O’Brien’s decision.

The second was a bigger story, and it underscores the rush to get out big news. Though January 12, 2010, was the day that the Haiti earthquake struck around 5 p.m., EST, no mention of this was made around the business desk. Instead, the news that had Getzfred and the rest of the business desk in breaking-news mode was Google’s announcement that it was — for now — pulling out of China because of security breaches.

The news was broken on the tech blog Bits. Getzfred then alerted the homepage to the news. The homepage didn’t like the wording and, after briefly posting the Bits blog, took it down and put up an AP story. Getzfred quickly wrote a roughly three-paragraph story on the statement to give a “staff presence on the page” and also to give the main reporters for the story a running start. Bits then reposted a new version, which Getzfred passed to the homepage, which the homepage liked. The full article then followed, updating Getzfred’s headline version, which stayed on the homepage until something more substantial was ready. Getzfred was motivated by speed and by his sense of pride in having a Times stamp on the story.

“Update, update, update” was the unwritten mantra for Getzfred, and as such, he kept a steady stream of stories flowing on to the business page website. When the business page went through an update in April 2010 to focus on even more immediate material, with the goal of highlighting new stories throughout the day, the emphasis on newness and constant updates only increased.

After reading a draft version of this book, Getzfred thought this made him appear like he was waiting for news to happen, when in fact, he felt that he was actively preparing for scheduled events he knew would generate news, working with reporters to generate prepared matter to respond to these news events, and making sure that stories were available as soon as possible on the web. Notably, though, this focus on the now, this ASAP need for content, underscores the importance of immediacy in online web rhythms. Though the print and web business pages started to converge in the evening, in part due to the slower trickle of content, the felt imperative during the day was for more new content, now. The business web page, and the homepage too, both paused online as The New York Times in New York went to bed, but in the morning, what was there would be gone, and the cycle would begin once again.

Thus, two dynamics were at play, print and online, and ultimately, print was the most important factor, not least because it occupied the value system that was most dear to traditional journalists. Immediacy meant two different things in a newsroom that had two processes of newswork ongoing at the same time. There was both the old world of immediacy, where breaking news meant tomorrow, and the new world of immediacy in online journalism, where immediacy meant “fresh” constant updates and where the homepage would not look the same in any way after six hours.

The print news cycle ultimately fed the homepage and the business web page with content — but generally, it took until the end of the day for the authority of print news to begin to inform how web stories would look online and what prominence they would have. By that point, most people would not be paying attention to NYTimes.com. By 9 p.m., when the major print stories for the day had been fully fleshed out, copy edited, and prepared, the homepage finally began to stop its immediate churn. The homepage editor, though, didn’t need any raw numbers or traffic data to have the sense that most people had long ago signed off of NYTimes.com, at least among readers in the United States, and that the busy focus on keeping readers on the page had long subsided. In fact, these numbers were not readily available to the web editors.

Yet by morning, the important stories from the print paper — the value-added content, the front-page stories — would be quickly washed away by stories with relatively small bits of significance. Sussman would be left with the previous night’s leftovers, some foreign stories coming in during the day, and filler stories from desks like business that were of such little significance that they might not even make the print paper.

On the other hand, we might see the website as doing quite well according to Times standards, despite moving so quickly. Even without the layers of editorial judgment, those charged with constantly updating the website do it well; they are trusted for their facile judgment and their competency as headline writers and copy editors, all their work done rapidly. These web editors have their own sense of traditional news norms; they do weigh the importance of each story, given the significance to readers — though in practice, this may not always work in the quest for “fresh” content, as we see with Getzfred and the early-morning business web page.

The compulsion to continually keep providing more content had become woven into the fabric of NYTimes.com; immediacy has created a system of worth, order, practice, and routine for online journalism. In this way, what journalists spoke of as “fresh,” and I conceptualize as immediacy, takes its shape as an emergent value of online journalism at the Times. Immediacy ordered how the majority of Times readers would see the newspaper’s content. What is missing from this conversation is the “why” for the focus on online updating. This had become incorporated into how web journalists understood their mission — and their sense of what was important — but other than the simple explanation that readers wanted to see what was new, there was little reflection on what made immediacy important. This further suggests that this value was emerging, as journalists had yet to define and truly reflect on its importance, beyond daily routine.

Culturally, NYTimes.com was not the print newspaper: there were no long meetings; multiple editors did not labor over what stories were placed where; and online moved quickly, all thanks to the imperative that more readers should see new content. Decisions were left to two people, generally, rather than a group of people debating what would be the agenda for the day. Perhaps at the end of the night, print created a pause, but during the day, a visitor to NYTimes.com would have no clear insight into what the “11 men and 7 women with the power to decide what was important in the world” considered the most important stories.

The great irony for this newspaper was that immediacy was a compulsion, but print remained, at least for the time, more important in setting the tone and significance for news stories in the daily rhythms of top editors and traditional journalists’ senses of order. The seemingly clear rules of print production did not always (and often did not) meet the needs of online news production. Thus, news making based on these two value systems suggested competing work routines. What we see is the process for shaping and creating public-facing content for readers, both print and online.

The tension between print and online immediacy is particularly poignant for traditional reporters, who must serve two masters. Though print matters more, the daily process of the web often captures their attention — creating competing pressures. For journalists, this uncertainty is often unwelcome and makes their lives quite difficult.

Screenshots of NYTimes.com front pages are from the end of the days cited in the text, after midnight, which is why they are dated the following day.