Should Facebook be allowed to decide what information we do or don’t see? Should Google be responsible for ensuring that their search results don’t offend or incriminate? If we allow platforms to determine what content and information we encounter, are we defaulting on our civic responsibilities?

Lately, it seems questions like these — questions about the algorithms that govern and structure our information networks — are raised more and more frequently. Just last week, people were outraged when it was discovered that Facebook had tried to study the spread of emotion by altering what type of posts 600,000 users saw. But the reality is we know less and less about how news content makes its way to us — especially as control of those information flows becomes more solidified in the hands of technology companies with little incentive to explain their strategies around content.

Lately, it seems questions like these — questions about the algorithms that govern and structure our information networks — are raised more and more frequently. Just last week, people were outraged when it was discovered that Facebook had tried to study the spread of emotion by altering what type of posts 600,000 users saw. But the reality is we know less and less about how news content makes its way to us — especially as control of those information flows becomes more solidified in the hands of technology companies with little incentive to explain their strategies around content.

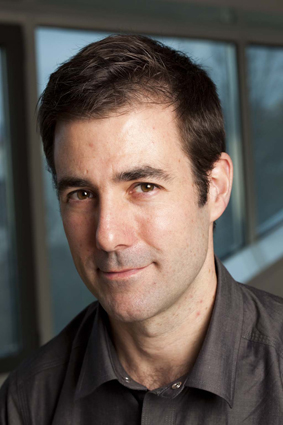

Tarleton Gillespie has done a considerable amount of writing on what we know about these algorithms — and what we think we know about them. Gillespie is an associate profesor of information science at Cornell, currently spending time at the Microsoft Research Center in Cambridge as a visiting researcher. We first met at the MIT Media Lab, where Gillespie gave a talk on “Algorithms, and the Production of Calculated Publics.” His writing on the subject includes a paper titled The Relevance of Algorithms and an essay called “Can an algorithm be wrong?” More recently, he contributed to Culture Digitally’s #digitalkeywords project with a piece on algorithms that explains, among other things, how it can be misleading to generalize the term.

We touched on the conflict between publishers and Facebook, Twitter trends, the personalization backlash, yanking the levers of Reddit’s parameters, and how information ecosystems have always required informed decision making, algorithms or no. Here’s a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

For me, I’ve been finding myself thinking about the term algorithm quite a bit in the last couple years. In part, it came from a research project that is my main project, which is thinking about how social media platforms govern speech that they find problematic. That could be classic categories like sex and violence, it could be hate speech, it could be an array of things. But the question is, how are they finding themselves in charge of this problem of removing things that are unacceptable — finding themselves as cultural gatekeepers as publishers and broadcasters have had to be — and how do they go about doing it? And how do they justify those techniques?

As I was trying to figure that out, I was thinking about a whole array of things — like putting things behind age barriers, or safe search mechanisms, or blocking by country — and I was calling them algorithmic techniques. That made me think about updating a long literature about how technology matters, how you can design things so as to govern use — but how do you do that in an algorithmic sense, rather than, say, in a mechanical sense?

Now you’ve got Facebook and Apple and YouTube being in a similar situation, but I think the game is different. You can do classic stuff, like setting rules and deciding where the line is, but the other thing you can do now is you can design the platform so that you manage where those things go. It’s not like there’s no precedent for that either — you can build a video rental store and put all the porn in the back room, and have rules about how gets in there and who doesn’t. That’s using the material architecture and the rules to keep the right stuff in front of the right people and vice versa. But you can do that with such sophistication when you think about how to design a social media platform. You know much more about people, you know much more about what their preferences are, about where they’re coming from, about the content. You can use the algorithm — the very same algorithm that’s designed to deliver what you searched for — to also keep way what they think you don’t want to see.

Journalism is the place where it got pushed back the most, because we have a public interest in not just encountering what we expect to see, that’s much stronger than the same feeling about advertising, right? I don’t like predicting the future, because I’m terrible at it, but the enthusiasm about personalization has shifted a bit.

In some ways, I feel like what we’re seeing now is throwing every possible kind of slice at us. Any slice — here’s what we think you want, here’s what we think you asked for, here’s what we think about what everyone else is doing, here’s what your circle of friends is doing, here’s what’s timely, here’s what’s editorially interesting, here’s what’s connected to our advertising — that in some ways giving us many slices through the available content, personalization just being one or maybe a couple of those.

I don’t think it’s going to go away. I think it remains one of the ways in which a platform can slice up what it has and try to offer it up. I do think the gloss has gone off it a little bit, and probably for a good reason.

I think what that hides is the way that, for a long time, we have navigated information in part through mechanisms that don’t belong to us that try very had to provide something for us. They weren’t always calculational: Music reviewers are an intensely important way that we decide to encounter things that’s both appealing to us and can work really well. When someone suggests something that we never would have heard, it’s completely moving to us, and exciting.

And we can be frustrated by it: These people are cultural gatekeepers. Are they attuned to what we really care about? Are they culturally biased? Elitist? We struggle with that. Similarly, when we deal with the quantified versions — the pop charts — is that an amazing glimpse of what people really are interested in? Or is it a weird artifact of what weird middle ground material can make it above all the more interesting stuff?

We’re always navigating information and culture by way of these mechanisms, and every mechanism has a built in notion of what it’s trying to accomplish. That’s the part we need to unpack. There’s always going to be a tool that says if you’re interested in this, listen to this. But the assumptions that tool makes about what it should look for, what it is we seek, and what’s important about that form of culture — whether it’s journalism or music or whatever — that’s the part we have to unpack.

But it seems like there would be room for a kind of explanatory clarity that’s not the same as giving away exactly how the algorithm works in specific terms, but that honors the fact that these different glimpses are different, and they differ in kind, not just sort of on the surface. Twitter has been relatively forthcoming about what Trends is, maybe as best as it could be.

But I like a model like Reddit. When you go to the top of Reddit, there’s about five choices of how to organize — there’s trending, there’s hot, there’s controversial — and you can read about what those things are. It’s not that that’s the perfect way to do it, but at least the fact that there are different slices reminds you that these slices are potentially different. I think that they could have a little justification about how they thought about it.

One of the things I found really interesting about Twitter Trends is that they’ll weight tweets or hashtags that appear across different clusters of people that aren’t connected to each other on Twitter higher than a lot of activity that happens in a densely connected cluster of people.

You can imagine the opposite choice, where something that happens in a cluster of people really intensely, but isn’t escaping — maybe that’s exactly what should be revealed. Something like: You may not know anything about this, but somewhere, there’s a lot of discussion about this, and you may want to know what that is. That’s fulfills a very different public or journalistic thing. Yes, there are things that seem to be talked about on a wide basis, and we want to reflect those back, but we also want to say, over here in the world, in a place you don’t have access to, there’s something going on.

Even if you just had those two things next to each other and talked a bit about how they’re different, you’d offer users a way to think about their difference and make choices. And it would push the platform to think about why the difference might matter.

Now, it’s not clear that Trending and Controversial and Hot and New are the right four slices, or do the work that I’m hoping it would do to reveal how these things are different.

In some ways, the other way you do this — and it starts to sound like personalization, but I don’t mean it this way — is to let the user play with the parameters of those differences. I don’t mean, Boy, I hope I could set it so I can get all domestic and no international — that’s the worst problem of personalization. But, show me Hot and show me Trending and show me Controversial, and then let me pull the levers and change the parameters a little bit, and see what that does to the ranking. That recognition that even one algorithm’s criteria shift based on the parameters, seeing that happen — not just knowing, intellectually, but seeing it happen — would be a pretty interesting glimpse into how much the choices are built into the apparatus.

The Times gets to say, We do great journalism. Then, on the other side of the coin you have a BuzzFeed, which is about as close as you can come to gaming a social algorithm, I think, but their reputation is bad in a lot of circles. Still, they’re reaching so many more people that way. I don’t know if there’s a way to have both, but it seems like there should be a middle ground.

It reminds us what an incredible mechanism it was to say, We’re going to be a newspaper that not only reports the story, writes the story, checks the story, produces the story, but then also manages turning it into paper, delivering it to street corners, having people sell it, managing subscriptions — that’s an incredible apparatus. We got used to that as a 20th-century arrangement, whether it was in newspapers or film or in television. But now that whole second half of — “We will also manage the circulation of this content” — is fractured enough that it’s just much harder to put the financial and emotional investment in the first half.

Then you have BuzzFeed, and what they’re doing with their data input and analytics, which as I said is about as close to gaming a social algorithm as you can get. How is BuzzFeed doing that? And what happens when there’s this mirrored back and forth?

Let’s say, for example, Facebook decides they want to downplay clickbait headlines. Theoretically, according to what BuzzFeed says about itself, they’re going to notice that. They’re going to notice that that trick is no longer working, and they’re going to come up with a new trick, and then the algorithm would have to change in reaction to that. Is that a logical characterization of that feedback loop? And is there any way to change it?

The other way to think of it is, they’ve got two forces to factor in. They’ve got to figure out Facebook’s algorithm, but they’ve also got to figure out the audience. For their stuff to drop off — let’s say they see a lag in the previous month — is that because Facebook tweaked their algorithm? Because people were less interested? Is that because they didn’t have as many interesting stories? Because no celebrities did anything embarrassing that month? It’s very hard to discern this, and that’s something cultural producers have had to do for a long time. Why didn’t people come to this movie? Was it that it was terrible? Was it that word of mouth was bad? Was it a bad weekend? Is it the mechanism by which the movie gets to the people, or was it the content? There’s a thin line between gaming the algorithm and trying to be appealing.

The funny thing about clickbait as an idea is it’s basically shorthand for: People really wanted to read this. Writing a really juicy headline to get people to read it, whether you got the substance or not, is not new to BuzzFeed and Upworthy. Is that gaming the algorithm? Was the algorithm of the penny newspaper — “You can see the front page on the shelf, and you can’t see the content in it, so those words better be big and gripping and delicious”? Is that gaming the algorithm for how newspapers were sold? Or is that just trying to get people to read your paper?

The last part of this is, as BuzzFeed has shown, if you’re beholden to the algorithm, what you do is not just sit there and try to guess the algorithm — you go and you meet with Facebook, and you strike a deal. That’s the real story — who’s going to get to strike the deal with providers, such that their stuff continues to stay on the network, or continues to be privileged.

But then a guy who works for Facebook ad product had a blog post about the state of media saying all media is garbage these days and why don’t we have good journalism anymore. Then there’s Alexis Madrigal of The Atlantic saying, among many others, what do you mean? We’re doing the best we can here, but we can barely get any play on your platform as it is, and if we just did serious investigative journalism, no one would ever read it, and it’s your fault.

How did we end up in a situation like that, and what can we do about it?

Now, it plays on slightly different lines. It’s not: We have to have a slate of programming that will draw big audience. It’s: We have a platform that calculates what people do and then responds to that. That means they can’t point to things differently. Instead of saying, we’ve got to make a buck at the end of the day — which of course they do — they can say, Look, it’s a user-driven mega-community.

Now, that’s a misrepresentation, I think, of the decisions that go into what the algorithm displays in the first place. But it’s not so different — the entity that helps deliver the news is not the same as the news, and their interests and their understanding of what they should be doing, and their commercial pressures, and how they came to do what they do, is not the same as having come into a kind of journalistic project from a journalistic standpoint.

Now, a solution? That’s harder. Do you call on these networks, on Facebook — and this is what Alexis Madrigal and Upworthy are doing — and say, You’ve got to look closer at the choices you’re making about your algorithm, because you are in fact putting us at a deficit and you shouldn’t? And when you say shouldn’t, shouldn’t according to what? According to some public obligation? It’s not clear that we expect Facebook to be a public service, even in the way that we expected NBC to be one.

But that last point is exactly right — we are in an information environment, and we always have been, where the best possibility of us being informed and thoughtful and ready to be participants in a democracy has always depended on other people. It’s always depended on other people to be closest to the information we need, which makes them risky, because they’re biased or subjective or emotional, but more importantly because they have to be participants in an institution that has to sustain itself, whether it’s a newspaper organization or a TV network or a social media platform. That raises all sorts of problems too, about why they’re really bringing the information to us that they are. I don’t think we can really get away from that.

So the only thing we can do is to continue to demand that these services provide what we think we need, the “we” being both individual and collective, and keep paying attention to the way they have structural problems in doing so. Whether that’s algorithm or editorial acumen or yellow journalism, these are just the kinds of problems that emerge when institutions try to produce information on a public and commercial basis across a technical platform. We’re just facing the newest version of that.